I spent most of the past week in California at the American Frozen Food Institute’s annual meeting (in San Diego) and the Global Food Safety Initiative conference in Anaheim. The weather was great and I got to hang out with Schaffner for a couple of days and talk podcasting, so that was cool.

Sealed Air invited me to speak at GFSI about using qualitative data to make decisions and guide behavior change in food handlers. In collaboration with Target and Insight Product Development, the Sealed Air folks carried out a project employing ethnography and video observation to evaluate and characterize behaviors in a sample of Target stores. The project focused on cleaning and sanitation. I was given the data and they asked for ideas on how to use it.

Here’s what I came up with (click here for my slides):

Quantitative data generated through internal and external audits/verifications/inspection/whatever tells a company frequencies and helps prioritize what needs to be worked on. Qualitative methods like ethnography is deeper and can help describe and characterize actual practices, and more importantly, why they are occurring.

Once you know what is going on, and why, a common risk management response is to train food handlers again, or more, or better.

Training more may not matter unless you can make the food handlers care.

The key from the behavioral model literature is two fold: food safety nerds might be more successful with front-line folks if they spend time on sharing the whys behind specific tasks as well as emphasizing that the individual has control over the positive and negative outcomes. Just being prescriptive is not only boring, it doesn’t connect with the audience.

This isn’t revolutionary, and what the food safety infosheets and infographics are based on, but paired with real life practices in real time, with a focus on emotion, training could be powerful.

Messages built on emotions seems to work in lots of situations. The Hindu reports that handwashing behaviors in Indian villages were positively impacted by messages focused on emotions of nurture and disgust.

The campaign, which was carried out by researchers from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and St John’s Research Institute, Bangalore, succeeded in doing so by changing an entrenched health behaviour using an unconventional approach — emotional drivers.

The use of emotional drivers is very different from the conventional health risk messaging that public campaigns often tend to use, suggests a paper published today (February 27) in The Lancet Global Health journal evaluating the hand wash campaign “SuperAmma” in Chittoor district.

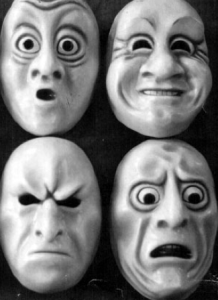

Through skits, animation films and posters, researchers experimented with four emotions like nurturing (“the desire for a happy, thriving child”) and disgust (“the desire to avoid and remove contamination”), to encourage people to wash their hands with soap before eating and cooking and after using the toilet or cleaning a child.

The team created a fictitious character called ‘SuperAmma’, “a forward thinking rural mother” to help communicate their message in schools and to the community.

Six months after the campaign was launched, evaluations showed a 37 per cent increase in handwashing rates in the intervention villages (these rates sustained for 12 months), while the rates remained fairly unchanged in the control group (which saw a 4 per cent increase), establishing that the campaign had achieved its goals.