When the bunch of us were writing our paper on the failures of audits and inspections, we had several disagreements about what was an audit, what was an inspection, what should be included, and so on.

I insisted that to consumers, it didn’t matter, and there were failures in both kinds of systems, we should highlight both and not get to hung up on the distinctions.

Sometimes you just have to get stuff out the door.

Sometimes you just have to get stuff out the door.

And sometimes you have to be an asshole (guilty).

Hopefully Canadian media is moving beyond its infatuation with political and company-versus-union rhetoric on food safety issues and starts asking, why aren’t farmers, processors, everyone, taking responsibility for their slice of food safety?

XL Foods has been silent and it’s disgraceful.

I would never want to buy their meat if they can’t stand behind it; but, as a lowly consumer, I have no way of knowing what meat is what at retail – large or small – and that’s why firms need to start marketing their food safety efforts to shoppers (but only if they can back it up, with data).

Sarah Schmidt of Postmedia writes in papers across Canada this morning that the Canadian Food Inspection Agency has vowed again to tighten the rules at slaughterhouses, as the country’s largest ever beef recall expanded Tuesday to more than 1,500 products.

But as the government continues to grapple with the massive recall of meat from the XL Food Inc’s facility in Brooks, Alberta, experts are probing why, four years after the federal government vowed to fix problems of food safety following a deadly listeriosis outbreak in deli meats, big gaps in the food safety system still exist.

This time, Canada’s second-largest slaughterhouse is at the centre of the potential E. coli O157:H7 beef contamination of hundreds of products, now linked definitively to five cases in Alberta of people becoming sick after eating tainted beef. Saskatchewan public health officials, meanwhile, are investigating whether a spike in E. coli cases in that province is connected to the Alberta plant.

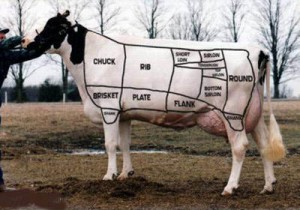

Richard Arsenault, CFIA’s director of meat inspection, said Tuesday the agency will establish a firm threshold that requires companies to divert or dispose of beef trimmings if positive test results for E. coli O157:H7 reach a certain percentage on “high event days” — i.e. days when higher than normal detections of E. coli O157:H7 are made. (Beef trimmings are material taken off the carcass that is not suitable for steak and is used for hamburger.)

“Nobody could agree on that number, so we essentially asked people to keep on eye and look at it. But there wasn’t a lot of structure about how people went at that,” Arsenault told Postmedia News. “I’m fairly confident we’re going to have that as well, I just don’t know what the number is going to be.”

The commitment to establish a threshold follows a pledge Monday by CFIA that it will also bring in a rule requiring companies to analyze test results of beef trimmings so they can identify emerging food-safety problems. “There certainly  was no requirement to start looking inside the data to see trends within a day’s production, and that’s something that definitely would have made a big difference if we had had that,” Arsenault said.

was no requirement to start looking inside the data to see trends within a day’s production, and that’s something that definitely would have made a big difference if we had had that,” Arsenault said.

But food-safety experts say the latest developments beg the question: Why do gaps still exist after the government announced last fall it had made good on all 57 recommendations that stemmed from a probe of the 2008 listeriosis outbreak. That outbreak was linked to Maple Leaf foods of Toronto.

Doug Powell, professor of food safety at Kansas State University, said Canada has no reason to brag about food safety, saying it’s in reactive mode — “and it’s largely driven by the U.S. All this food safety stuff, you think it’s about human health, really it’s about trade,” said Powell.

The XL Foods plant at the centre of the storm remains shut following an in-depth CFIA investigation at the plant. “The in-depth review determined that the company’s decision document requires updates and modification to address the disposition of production high event days,” CFIA said in a statement Tuesday.

CFIA’s move to suspend XL’s licence, announced on Sunday, followed a decision by U.S. officials to bar shipments from the Brooks plant on Sept. 13.

An independent audit of the Brooks plant commissioned by XL Foods last May found that the facility considers an “event day” for the purposes of product disposition if more than 10 per cent of tests are positive for E. coli. Under the N-60 sampling program, companies are required to test at least 60 pieces of beef trimmings per lot. This means that whether a lot weighs 4,500 kg, 2,000 kg or 100 kg, 60 sub-samples must be collected from the lot to be tested.

In the United States, the Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) released a compliance guide in May for operators of large slaughterhouses, saying five per cent should be the threshold for the diversion of a batch of beef trimmings.

“FSIS intended to identify criteria that would indicate exceptional events of poor processing. FSIS did not select a higher target (e.g., 10%) because such a target we believe could result in many cases where poor processing, as defined by most in the industry, would not be detected as a ‘high event period,’ ” the U.S. report states.

Powell says government should be establishing minimum standards for all food-safety practices — and farmers, companies and restaurants should “go far beyond” these standards.

“You have to lower pathogen loads all the way through the system, and the way to do that is for everyone to take their food safety responsibility seriously, and that’s why we focus on a culture of food safety. Everything that I’m seeing in Alberta is ‘process as much meat and make as much money,’ ” said Powell.

“I watch these political debates emerge every time there’s a really tragic outbreak. People get really sick. There’s a four-year-old kid in the hospital with kidney damage. Nobody’s talking that. They’re talking about beef farmers losing money,” Powell added.

Kevin Allen, a food microbiologist at the University of British Columbia, says Canada should look south of the border for answers. He said, “Something wasn’t working right” at the XL foods plant, overseen by 40 government inspectors and six veterinarians.

“When you look at U.S. policy, they have a zero tolerance. They will simply not tolerate the presence of this organism in their beef and I think that’s a much more proactive approach, where food safety and the possible consequences are put first and foremost,” said Allen.

Rick Holley, a professor of food science at the University of Manitoba, disagrees with Allen on a zero-tolerance policy on E. coli 0157:H7, but he’s clear on one thing: beef eaters shouldn’t take huge comfort when the government talks about how much better equipped it is to prevent, detect and respond to potential food safety risks because it implemented all of the food-safety recommendations from four years ago.

“We’re no different from where we were four years ago,” said Holley.

that they either need new management or new ownership, because the Nilsson brothers were obviously out of their league in running this company.”

that they either need new management or new ownership, because the Nilsson brothers were obviously out of their league in running this company.” do. Plants are always going to have challenges.”

do. Plants are always going to have challenges.”