Oh Canada. Why stand on guard for mediocrity?

In 1985, 19 of 55 sickened at a London, Ontario nursing home were killed by E. coli O157:H7 in their roast beef sandwiches.

The Ontario government called for mandatory training for food service types in health care institutions. The same ones that thought it was a good idea to serve  chilled deli meats to immunocomprimised elderly folks in 2008 that lead to 23 deaths from Listeria.

chilled deli meats to immunocomprimised elderly folks in 2008 that lead to 23 deaths from Listeria.

I needed 36 hours of training to coach little girls hockey; no one needs anything to kill people with food.

In 2000, seven died and 2,500 were sickened in the town of Walkerton, Ontario, population 5,000, when E. coli O157:H7 got into the drinking water supply and the local manager added chlorine to the system based on smell.

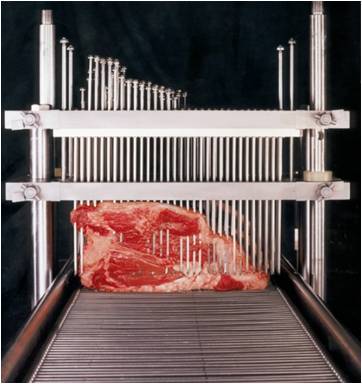

In 2012, XL Foods in Alberta sickened 18 people with E. coli O157:H7, and led to the largest beef recall in Canadian history, and the plant was subsequently bought by JBS of Brazil.

Following in the tradition of Walkerton and Maple Leaf’s listeria, an independent review panel has concluded the outbreak was caused by mediocrity.

Perhaps I’m paraphrasing.

The Globe and Mail isn’t.

The largest beef recall in Canadian history happened because a massive Alberta producer regularly failed to clean its equipment properly, reacted too slowly once it realized it was shipping contaminated meat, and on-site government inspectors failed to notice key problems at the plant.

“It was all preventable,” concludes an independent review of the 2012 XL Foods Inc. beef recall, in which 1,800 products were removed from the Canadian and U.S. markets and 18 consumers became sick.

According to the report, the company did not practice what to do in the event of a major recall, and its staff failed to ensure equipment was regularly and  properly cleaned. Canadian Food Inspection Agency workers at the plant failed to notice the problems. These and many other issues persisted four years after the government promised sweeping food-safety reforms in response to the 2008 listeria bacteria contamination at Maple Leaf Foods that took the lives of 23 Canadians and led to serious illness in 57 others who ate tainted meat products.

properly cleaned. Canadian Food Inspection Agency workers at the plant failed to notice the problems. These and many other issues persisted four years after the government promised sweeping food-safety reforms in response to the 2008 listeria bacteria contamination at Maple Leaf Foods that took the lives of 23 Canadians and led to serious illness in 57 others who ate tainted meat products.

“It was not that long ago,” the report notes in reference to the 2008 recall. “Canada’s food-safety system – then, as now – is recognized as one of the best in the world. Yet, a mere four years later, Canadians found themselves asking how this could have happened once again.”

No, Canada exists in a bubble, with comfortable fairy tales about the best health care in the world and the safest food in the world.

Any outside observer could look at the available data and say, What ….?

The panel said “it was a series of inadequate responses by two key players in the food-safety continuum that played the most critical part leading to the September, 2012, event at XL Foods Inc. – plant and CFIA staff.”

Will Canadian reporters please stop quoting union officials, government types and industry apologists – and they are abundant – because they are all complicit in the rewarding of mediocrity, even when a lot of people get sick.

The panel was chaired by Ronald Lewis and included two other doctors, André Corriveau and Ronald Usborne. They report the root cause of the problem was likely an animal that was heavily contaminated with E. coli-157:H7.

“As the contaminated carcass moved through the plant, the bacteria became lodged in or on a piece of equipment within the establishment,” the report states. “It seems likely that sanitation was inadequate.”

The report is highly critical of XL Foods Inc. for its poor communication with both the CFIA and the public, particularly for not providing CFIA with information about the contamination quickly after it was discovered. The  company was sold earlier this year to JBS South America of Brazil. However, the independent review also found several issues with the performance of the CFIA.

company was sold earlier this year to JBS South America of Brazil. However, the independent review also found several issues with the performance of the CFIA.

“For its part, CFIA was clearly not monitoring the company’s [Food Safety Enhancement Program] and identifying deficiencies as carefully as they should have been,” the report states.

The report makes 30 recommendations for reform, including a call for Health Canada to give “prompt consideration” to approving irradiation of Canadian beef products. It also calls on the Minister of Health to assess the effectiveness of the CFIA’s activities related to its meat program.

Here’s a different suggestion: anyone that produces food for public consumption assumes a responsibility of safety; the best companies will brag about their safety shield, rather than hide behind the cloak of shitty government inspection.

At a news conference, the inexplicably still employed federal Agriculture Minister Gerry Ritz spouted some recycled shit about a new inspection verification system with a team of 30 inspectors at a cost $16-million over three years, and promised to act on all the recommendations because “Canadian consumers remain our No. 1 priority when it comes to food safety. As we all know, no system is perfect.”

Pump up the mediocrity.

Paul Mayer, vice-president at the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, told a telephone news conference that these teams will be “a second set of eyes” to check both the food companies and the front-line CFIA staff. That speaks to the chief recommendation the study team made – that the companies and CFIA need to foster a culture of food safety.

Food safety culture has definitely jumped the shark

If the first set of eyes isn’t working, why would a second?

Pump, pump, pump up the mediocrity.

As Jim Romahn writes, the company clearly comes off worst, but the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, producers and retailers all share some responsibility for the biggest beef recall in Canadian history – 4,000 tonnes of beef, 1,800 products distributed across Canada and into the United States. Exports to 20 nations were impacted, especially to Japan and Hong Kong.

Meat and any food suppliers or producers should market safety at retail. There’s been too much faith, too many sick peope, and too many repetitive reports sayig the same thing. Let consumers choose, and brag about food safety.

Or wait till the next outbreak and appoint a panel to come to the same Groundhog Day conclusions.

The lawsuit was against XL Foods Inc., which operated a meat-packing plant in southern Alberta during the tainted beef recall in the fall of 2012.

The lawsuit was against XL Foods Inc., which operated a meat-packing plant in southern Alberta during the tainted beef recall in the fall of 2012.