On Sunday, May 21, 2000, at 1:30 p.m., the Bruce Grey Owen Sound Health Unit in Ontario, Canada, posted a notice to hospitals and physicians on their web site to make them aware of a boil water advisory for Walkerton, and that a suspected agent in the increase of diarrheal cases was E. coli O157:H7.

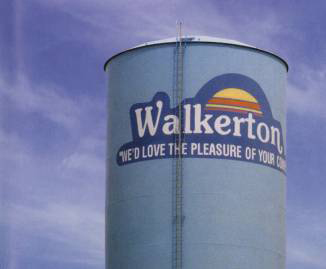

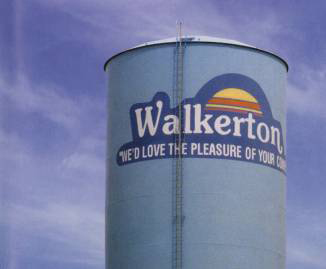

Not a lot of people were using RSS feeds, and I don’t know if the health unit web site had must-visit status in 2000. But Walkerton, a town of 5,000, was already rife with rumors that something was making residents sick, and many suspected  the water supply. The first public announcement was also the Sunday of the Victoria Day long weekend (which happens this weekend in Canada) and received scant media coverage.

the water supply. The first public announcement was also the Sunday of the Victoria Day long weekend (which happens this weekend in Canada) and received scant media coverage.

It wasn’t until Monday evening that local television and radio began reporting illnesses, stating that at least 300 people in Walkerton were ill.

At 11:00 a.m., on Tuesday May 23, the Walkerton hospital jointly held a media conference with the health unit to inform the public of outbreak, make the public aware of the potential complications of the E. coli O157:H7 infection, and to tell the public to take necessary precautions. This generated a print report in the local paper the next day, which was picked up by the national wire service Tuesday evening, and subsequently appeared in papers across Canada on May 24.

The E. coli was thought to originate on a farm owned by a veterinarian and his family at the edge of town, a cow-calf operation that was the poster farm for Environmental Farm Plans. Heavy rains washed cattle manure into a long discarded well-head which was apparently still connected to the municipal system. The brothers in charge of the municipal water system for Walkerton were found to add chlorine based on smell rather than something like test strips, and were criminally convicted.

Ultimately, 2,300 people were sickened and seven died. All the gory details and mistakes and steps for improvement were outlined in the report of the Walkerton inquiry, available at http://www.attorneygeneral.jus.gov.on.ca/english/about/pubs/walkerton/.

Today, as the 11th anniversary of the Walkerton outbreak approaches, Canadian Press reports the Ontario government has paid out more than $72 million in compensation to victims of Walkerton’s tainted water tragedy and their families.

Ontario Attorney General Chris Bentley says over 99 per cent of the more than 10,000 compensation claims have been resolved, and the remainder are supposed to be resolved by the end of this year.

A total of 10,189 claims were made, with 9,275 qualifying for compensation.

Bentley says while nothing will ever make up for the tragedy experienced in Walkerton, he hopes the compensation plan has helped all those who suffered continue along the path to healing.

Among the 121 recommendations on an inquiry aimed at preventing a recurrence of the public-health disaster were ones geared toward mandatory training and certification for water-system operators.

.jpg) of a boil water advisory and that a suspected agent in the increase of diarrheal cases was E. coli O157:H7.

of a boil water advisory and that a suspected agent in the increase of diarrheal cases was E. coli O157:H7.