I had this advisor 30 years ago who thought ribosomes were the center of the universe.

I had an ex-wife who thought veterinarians were the center of the universe.

I had an ex-wife who thought veterinarians were the center of the universe.

I know less and question more.

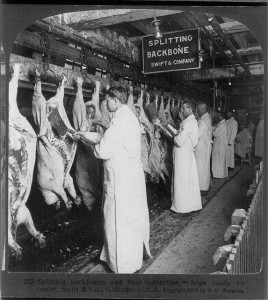

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, a fast-reproducing genus of bacterium, Salmonella, can—depending on the group, or serotype—be a virulent pathogen that sickens farm animals and humans.

Now, Agricultural Research Service veterinary medical officer Jean Guard has developed an improved, cost-effective diagnostic tool and dataset for identifying various strains of Salmonella. The tool, called “Intergenic Sequence Ribotyping,” or ISR, is helping improve poultry production and human health internationally, because it helps control Salmonella’s presence in the field and in consumer poultry products.

At present, there are other sequence, or DNA-based, methods for serotyping Salmonella. The traditional method, Kauffmann-White (KW), is expensive, is not based on DNA, and is not as accurate as ISR. “KW identifies a particular serotype in only 80 percent of cases,” says Guard. “We can get unknowns on the other 20 percent of the samples.”

ISR is being used to serotype strains within a particularly virulent group called Salmonella enterica, which is the type associated with foodborne illness. ISR tested well when compared with KW for the ability to identify strains among 139 samples of S. enterica that had been submitted from a variety of farms.

“Decreasing the cost of serotyping S. enterica while maintaining reliability may encourage routine testing and early detection of Salmonella by producers who have an in-house laboratory with trained personnel,” says Guard. “Smaller farmers without an in-house lab can work with a diagnostic consultant who has access to both the ISR tool and dataset.”

Guard makes the ISR technology available to any specialized laboratories, producers, or other qualified users who sign a proprietary Material Transfer Agreement (MTA). MTA holders both contribute to and have access to the proprietary ISR-based dataset, which is curated by Guard. “Each text file represents one serotype, or group, that has common elements,” says Guard. “These files include individual sequences of DNA letters—each a little different from another—this is how we expand the dataset.”

A producer’s lab technician can test a sample for Salmonella by culturing and if positive, submit that sample to a specialized lab—also an MTA holder—that uses the ISR tool for sequencing. “The lab then simply sends the sequence results back to the producer by entering the sequence into a private online account,” says Guard. Producers and diagnostic consultants who hold an MTA can access their private accounts to download their sequences. They then compare their sequences to those in the ISR-based dataset for a perfect match.

A producer’s lab technician can test a sample for Salmonella by culturing and if positive, submit that sample to a specialized lab—also an MTA holder—that uses the ISR tool for sequencing. “The lab then simply sends the sequence results back to the producer by entering the sequence into a private online account,” says Guard. Producers and diagnostic consultants who hold an MTA can access their private accounts to download their sequences. They then compare their sequences to those in the ISR-based dataset for a perfect match.

Guard says the ISR technology provides an early-warning system for farmers. For example, while one producer had no Salmonella problem detected on the farm, the ISR technology located a problem truck where clean birds were being infected after having been loaded for transport. “ISR led to identifying a single trucker who needed to disinfect the truck,” says Guard.

Right now, ISR is being used by university laboratories, colleagues in South America, and a large U.S. provider of breeding-stock animals. A pharmaceutical company also is using the ISR tool in vaccine development.