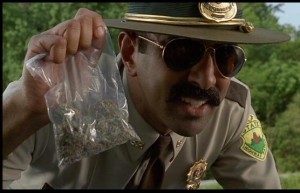

I treat all food like hazardous waste.

Editor Mark Katches writes that Lynne Terry of The Oregonian/OregonLive began writing about the federal government’s alarming handling of Salmonella outbreaks caused by store-bought chicken that began in the Pacific Northwest.

She found that over the course of a decade, the U.S. Department of Agriculture had not one, not two, not three, but four opportunities to warn the public about salmonella outbreaks involving Foster Farms chicken. Each time, the agency hemmed and hawed.

She found that over the course of a decade, the U.S. Department of Agriculture had not one, not two, not three, but four opportunities to warn the public about salmonella outbreaks involving Foster Farms chicken. Each time, the agency hemmed and hawed.

Terry was the first journalist in America to identify and write about this trend. But it didn’t come easily. She learned that reporters from Frontline, The Center for Investigative Reporting and the New York Times were circling around the story as she entered the final stages.

“It was tough,” said Terry, about the competition. “I felt this story was mine from the beginning, and I didn’t want anyone else to break it. It’s in our backyard. I had inside sources. I knew this stuff. So I did what anyone would do: I worked long hours every day for months on end to bring it home.”

Terry indeed got the scoop. Her “A Game of Chicken” project turned out to be a stunning and illuminating examination of the way the USDA operates.

And this week, the American Health Care Journalists awarded her first place in the public health category, beating out stiff competition from the Chicago Tribune and Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

In her investigation that spanned more than a year, Terry set out to determine if the USDA’s slow handling of a major salmonella outbreak in 2013-2014 was an isolated case.

It wasn’t.

She reviewed thousands of pages of previously undisclosed documents dating back to 2003. What she found was disturbing: More than 1,000 people had rushed to their doctors with bouts of food poisoning. Regulators had strong evidence pointing to the cause of the outbreaks but took virtually no steps to protect consumers from tainted chicken. Health officials in Oregon and Washington had pushed vigorously for federal action, having identified clear and convincing evidence of problems. But the USDA wouldn’t budge. Terry got a big assist from senior watchdog reporter Les Zaitz, who was serving as investigations editor at the time. And video producer Teresa Mahoney’s remarkable video helped break down complex issues in a compelling way while also warning consumers to thoroughly cook their chicken to 165 degrees.

Terry’s meticulous reporting showed that USDA officials were so fearful of being sued by the companies they regulate that the agency had set an almost impossible bar for evidence, even rejecting samples of tainted chicken that state health agencies believed would help clinch their case.

She also found out that government inspectors were under pressure to go easy on food processors. In one notable case, the USDA transferred an inspector after Foster Farms complained he wrote too many citations.

The agency rejected a wide-ranging Freedom of Information Act request. We appealed the denial and won. But months passed before the USDA finally released any records. Many of the documents were heavily redacted – often with entire pages blacked out.

“They refused records requests, and didn’t release anything for more than a year,” Terry said.

She filed more FOIA requests. And then more. The agency dribbled out partial releases, sending something every four or five months in response to our requests for updates. The federal agency’s attempts to stonewall Terry were even chronicled in a Columbia Journalism Review article lauding The Oregonian’s persistence.

She filed more FOIA requests. And then more. The agency dribbled out partial releases, sending something every four or five months in response to our requests for updates. The federal agency’s attempts to stonewall Terry were even chronicled in a Columbia Journalism Review article lauding The Oregonian’s persistence.

Terry overcame other obstacles. Foster Farms sent two foreboding letters to The Oregonian/OregonLive before we published. After the stories appeared, the company didn’t question the accuracy of our reporting.

Despite these hurdles, Terry was able to piece together a story of bureaucratic failure that had devastating human consequences. She found victims of salmonella poisoning who were willing to share their stories. She translated complicated epidemiological information into language readers could understand. She tracked down key documents. And she built the trust of USDA inspectors, who feared losing their jobs if they spoke out.

Her work was cited by members of Congress. In Oregon, Sen. Laurie Monnes Anderson, D-Gresham, referred to the investigation while she was arguing for a Senate bill that would limit antibiotic use in farm animals. Terry’s reporting also emboldened other USDA inspectors to come forward and tell their stories.

We went to extraordinary lengths to ensure “A Game of Chicken” was fair and totally accurate. Our lawyers reviewed drafts at least four times at our request.

It would have been easy to have been pushed by the swirling competition to publish as fast as possible. But that can sometimes introduce errors if reporters and editors short-hand the bullet-proofing process. Our watchdog motto is to publish when we’re ready. Or in this case, fully cooked.

Here’s a transcript of the Q&A with Oregonian/OregonLive health reporter Lynne Terry.

How long did it take to tell this story?

Longer than it should have, thanks to foot-dragging by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. I put in my first public records request in spring 2013 and filed several more through 2014. I worked on the story sporadically over a year or so but then dug into the trenches in autumn 2014 when they started responding to public records and I landed an inside contact. I worked nonstop for about eight months before we published.

What were the biggest complications?

Four initials: USDA. They refused records requests, and didn’t release anything for more than a year. They were wearing me down, frankly. Fortunately, Les Zaitz got involved. He was our investigations editor. He was a huge help in pushing the USDA. We never did get their enforcement data, however.

How did it affect you knowing that Foster Farms was sending seemingly threatening letters before we published?

At the time? It made me nervous. I don’t even like covering courts, let alone testifying. And the thought of The O being dragged into court because of my reporting was scary. But in retrospect, I think they helped us. We knew we had to have a rock solid package, and we did. We didn’t hear a peep from the USDA or Foster Farms after we published.

What impact did it have knowing that a number of other media were swirling around pieces of this story?

It was tough. I felt this story was mine from the beginning, and I didn’t want anyone else to break it. It’s in our backyard. I had inside sources. I knew this stuff. So I did what anyone would do: I worked long hours every day for months on end to bring it home.

Were you ever close to giving up on this story?

Several times. I was floundering when you came to The O. I was pretty much working on my own. I knew I had a good story but my editors were too busy with the daily churn. I was, too. Getting time to focus on it helped. Having Les to work with was crucial.

What has been the reaction?

I got quite a few emails from members of the public who said they’ve stopped eating chicken. Foster Farms has stepped up its internal controls and now says it has the safest chicken in the country. The USDA has tightened its regulations over salmonella but it has not banned the bacteria even though it sickens more than a million people a year.

Has this story changed the way you look at chicken?

Yes. I’ve not had chicken much since. There’s one quote that sticks with me. An Oregon epidemiologist said: “Treat it like hazardous waste.” That’s a bit of an appetite killer.

With this change, FSIS will begin to require that veal calves that are brought to slaughter but cannot rise and walk be promptly and humanely euthanized, and prohibited from entering the food supply. Previously, FSIS has allowed veal calves that are unable to rise from a recumbent position to be set aside and warmed or rested, and presented for slaughter if they regain the ability to walk. FSIS has found that this practice may contribute to the inhumane treatment of the veal calves. This change would improve compliance with the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act by encouraging improved treatment of veal calves, as well as improve inspection efficiency by allowing FSIS inspection program personnel to devote more time to activities related to food safety.

With this change, FSIS will begin to require that veal calves that are brought to slaughter but cannot rise and walk be promptly and humanely euthanized, and prohibited from entering the food supply. Previously, FSIS has allowed veal calves that are unable to rise from a recumbent position to be set aside and warmed or rested, and presented for slaughter if they regain the ability to walk. FSIS has found that this practice may contribute to the inhumane treatment of the veal calves. This change would improve compliance with the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act by encouraging improved treatment of veal calves, as well as improve inspection efficiency by allowing FSIS inspection program personnel to devote more time to activities related to food safety.