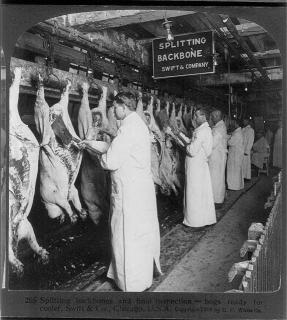

It’s a recurring story, one that Jim Romahn has reported on for decades: the good meat gets exported, the inferior stuff stays at home.

It’s the same with Australian seafood, unless you know where to buy.

It’s the same with Australian seafood, unless you know where to buy.

According to Canadian union thingy Bob Kingston, cuts to Canada’s food inspection programs have created a double standard, where meat sold to Canadians is not as well inspected than that destined for export.

“Lives are at risk, [there’s] the real likelihood that people will die. And I hope they wake up to this.”

At a news conference in Edmonton today, Kingston said since January, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) has quietly rolled back inspections at meat plants in northern Alberta. Increased inspections were put in place following a 2008 listeriosis outbreak tied to Maple Leaf Foods products, which resulted in 22 deaths.

“There’s no public debate. There isn’t even an industry debate about what’s going on. It’s the rollback of those commitments to protect Canadians,” he said.

He said the CFIA has cut the presence of inspectors in facilities from five days a week to three – but only in plants that produce meat for the domestic market. The presence of inspectors in plants inspecting for export have stayed the same.

Dr. Sylvain Charlebois, a University of Guelph professor who studies food safety, said the changes do not mean Canadian meat is less safe to eat.

“I don’t think the health of Canadians has been compromised,” he said.

“Canadian-destined meat doesn’t get less attention. It just gets different attention.”

He said given the CFIA’s resources, the agency’s changes are the “right way” to approach inspections. Reducing inspections of plants making domestically bound meat was done because the government has confidence in those facilities. Putting resources towards protecting exports is a vital task, he argued.

Charlebois don’t know much about food safety.

Keith Warriner, director of the food safety and quality assurance program at the University of Guelph, who knows more, said the implication that the meat sold in Canada is unsafe is “a little bit of scare-mongering.”

He said the union’s argument, that fewer inspectors inherently means people are at risk, isn’t true.

“If you had a policeman on every corner, yes, crime might go down,” he said.

“But the better thing is, isn’t it, to instill into people not to commit the crime in the first place.”

Warriner pointed to events like the 2012 E. coli outbreak centred around beef from the XL Foods plant in Brooks, Alta., which sickened over a dozen people. He said in that case, the plant had enough inspectors, but that they were not doing the work properly.

He said a much better solution is to get the meat industry to “take ownership” of food safety.

“You can’t test your way to food safety. You can’t inspect your way to food safety,” he said.

Instead, Warriner would like to see most of the inspection duties being handled by the plants themselves, with federal inspectors looking over a company’s internal inspection records.

Yes, we wrote a paper about that:

Audits and inspections are never enough: A critique to enhance food safety

30.aug.12

Food Control

D.A. Powell, S. Erdozain, C. Dodd, R. Costa, K. Morley, B.J. Chapman

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0956713512004409?v=s5

Abstract

Internal and external food safety audits are conducted to assess the safety and quality of food including on-farm production, manufacturing practices, sanitation, and hygiene. Some auditors are direct stakeholders that are employed by food establishments to conduct internal audits, while other auditors may represent the interests of a second-party purchaser or a third-party auditing agency. Some buyers conduct their own audits or additional testing, while some buyers trust the results of third-party audits or inspections. Third-party auditors, however, use various food safety audit standards and most do not have a vested interest in the products being sold. Audits are conducted under a proprietary standard, while food safety inspections are generally conducted within a legal framework. There have been many foodborne illness outbreaks linked to food processors that have passed third-party audits and inspections, raising questions about the utility of both. Supporters argue third-party audits are a way to ensure food safety in an era of dwindling economic resources. Critics contend that while external audits and inspections can be a valuable tool to help ensure safe food, such activities represent only a snapshot in time. This paper identifies limitations of food safety inspections and audits and provides recommendations for strengthening the system, based on developing a strong food safety culture, including risk-based verification steps, throughout the food safety system.

.jpg) Does inspection result in fewer sick people

Does inspection result in fewer sick people.jpg) Agriculture is a competitive modern industry, and changes will modernize Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada allowing it to concentrate on innovation, marketing and reducing barriers for business.”

Agriculture is a competitive modern industry, and changes will modernize Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada allowing it to concentrate on innovation, marketing and reducing barriers for business.”

.jpg) Does inspection result in fewer sick people?

Does inspection result in fewer sick people?.jpg) other procedures; to control animals and products at frontiers; and to require the destruction and safe disposal of animals and all articles considered to present a risk of disease transmission and to public health. These activities represent the core activities of veterinary services in the field of animal health control and veterinary public health and the legislation must provide the necessary authority as a minimum.”

other procedures; to control animals and products at frontiers; and to require the destruction and safe disposal of animals and all articles considered to present a risk of disease transmission and to public health. These activities represent the core activities of veterinary services in the field of animal health control and veterinary public health and the legislation must provide the necessary authority as a minimum.”.jpg) He doesn’t say why.

He doesn’t say why. Now she’s just boring.

Now she’s just boring.  The union is calling on Sodexo to provide greater transparency about the origin of the food they will be serving athletes, including: disclosing the primary supplier of the food that they will serve to athletes and whether those companies have had problems with contaminated food; whether the food will come from a "cook and chill" facility or will be cooked and served on-site; and to make the steps they are taking to ensure food safety easily available to the public.

The union is calling on Sodexo to provide greater transparency about the origin of the food they will be serving athletes, including: disclosing the primary supplier of the food that they will serve to athletes and whether those companies have had problems with contaminated food; whether the food will come from a "cook and chill" facility or will be cooked and served on-site; and to make the steps they are taking to ensure food safety easily available to the public.