The feds are doing a lot of chest-thumping as the XL slaughterhouse in Alberta struggles to reopen, what with 17 now sick from E. coli O157:H7 linked to beef from the plant.

Such behavior is absolutely expected, because the Canadian Food Inspection Agency has to do something publicly to convince Canadians they are on the ball, so they, and everyone else can go back to sleep.

Why these deficiencies were never noticed by the 40 inspectors and six veterinarians at the plant until people started getting sick – and even then it took days if not weeks for the  system to kick in – has never been adequately explained.

system to kick in – has never been adequately explained.

Never will be.

The delays in reporting the listeria-in-Maple-Leaf cold cuts in 2008 that killed 23 Canadians generated a similar response. Why the same Minister is still responsible for the same CFIA, and why the union still says the solution is more inspectors speaks only to the rise of mediocrity in Canada.

According to a CFIA statement, On October 29, 2012, Establishment 38, XL Foods Inc., resumed slaughter activities and operations under enhanced CFIA surveillance and increased testing protocols.

Over the course of the first week of operations, the CFIA determined that the establishment’s overall food safety controls were being effectively managed.

As would be expected in a facility that has not been in regular operation for some time, there have been some observations made by CFIA that resulted in the CFIA issuing new Corrective Action Requests (CARs) to XL Foods Inc. since the plant reopened. These observations included:

• condensation on pipes in the tripe room;

• water in a sanitizer was not maintained at a high temperature;

• meat cutting areas were not adequately cleaned; and,

• no sanitizing chemical solution in the mats used for cleaning employees’ boots.

The CFIA instructed plant management to take immediate action to address these concerns, including the following:

Potentially contaminated product was sent for rendering.

Sanitizers were brought into compliance immediately.

The meat cutting area was cleaned and sanitized.

Boot mats were supplied with sanitizer.

My comments are: why wasn’t potentially contaminated product dumped in a landfill like the other meat and how is that decision made between rendering and dump; were sanitizers ever in compliance and why did no one notice; was the meat cutting area ever clean, and did boot mats ever have sanitizer?

As reported in Canadian Business, “Companies have the primary responsibility for food safety,” says Rick Holley, a professor of food science at the University of Manitoba. “Without that, we’re all screwed.”

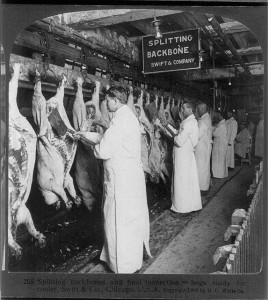

To reduce the chances of another XL debacle, the solution isn’t more inspectors or better processes. Instead, the meat industry needs to do the one thing it has so far avoided: talk openly and publicly about the manufacturing process. In short, it’s time for them to show us how the sausage is made.

Doug Powell, a food scientist and professor at Kansas State University has simple advice to food producers: “Provide information to consumers so that they can choose and reward those companies with good food-safety practices.” Consumers who currently want to  select a package of ground beef at a grocery store based on which producer is safest are out of luck. Some meat products, such as chicken breasts, feature brand names like Maple Leaf, but for others it’s unclear where they were actually produced.

select a package of ground beef at a grocery store based on which producer is safest are out of luck. Some meat products, such as chicken breasts, feature brand names like Maple Leaf, but for others it’s unclear where they were actually produced.

Compare that to the restaurant industry. Many municipal governments have instituted a report-card system so patrons can gauge a restaurant’s safety record before deciding where to dine. Before buying meat at a grocery store, safety-conscious consumers should be able to go to a producer’s website to learn about the risks associated with the products, what the company does to mitigate those risks, where mistakes have been made in the past, and how they’ve been rectified. Companies can essentially use safety as a competitive advantage. “I would argue food safety is a pretty good money-maker,” Powell says.

Consider how corporations in other sectors have differentiated themselves by trumpeting their dedication to safety. Volvo advertised its safety record more aggressively in the U.S. in the 1960s and 1970s when the government instituted stricter automobile regulations. “It shouldn’t take an act of Congress to make cars safe” was one memorable tag line. Newspaper ads detailed how the company installed seat belts and padded dashboards years before it became mandatory, and explained how Volvo continued to exceed government standards. There is arguably even more opportunity now for a food producer to stand out than there was for Volvo decades ago. A whole variety of factors influence car-buying decisions. When consumers buy ground beef, however, they might consider price, but that’s it. Drawing attention to safety is one way to differentiate your product.

Opening up is risky, naturally, and no company is enthusiastic about challenging the status quo. So meat processors have remained steadfastly opaque, both here and in the U.S., Powell says.

_story(1).jpg) bench – these are some of the restaurant nightmares being kept from the (Queensland) public.

bench – these are some of the restaurant nightmares being kept from the (Queensland) public..jpg) After watching the mish-mash of federal, state and local approaches to restaurant inspection in a number of western countries for the past 20years, I can draw two broad conclusions:

After watching the mish-mash of federal, state and local approaches to restaurant inspection in a number of western countries for the past 20years, I can draw two broad conclusions:.jpg) a culture that values microbiologically safe food and a work environment that rewards hygienic behavior. But mandating basic training is a start.

a culture that values microbiologically safe food and a work environment that rewards hygienic behavior. But mandating basic training is a start.

.jpg) 11 Quaker oats products will soon carry labels on the front of their packaging trumpeting a relationship between oat fibres and reduced cholesterol.

11 Quaker oats products will soon carry labels on the front of their packaging trumpeting a relationship between oat fibres and reduced cholesterol. n Conseil National de l’Alimentation’s newsletter No. 13, dated June 11, 2010, we learn about health safety: an increased effort between the three unions of the Groupement National de la Restauration.

n Conseil National de l’Alimentation’s newsletter No. 13, dated June 11, 2010, we learn about health safety: an increased effort between the three unions of the Groupement National de la Restauration..png) from the barfblog team, see, “Food safety information posted in restaurant kitchens can improve meal safety.” Source: Chapman, Benjamin; Eversley, Tiffany; Fillion, Katie; MacLaurin, Tanya; Powell, Douglas. Assessment of Food Safety Practices of Food Service Food Handlers (Risk Assessment Data): Testing a Communication Intervention (Evaluation of Tools). Journal of Food Protection®, Volume 73, Number 6, June 2010, pp. 1101-1107(7).

from the barfblog team, see, “Food safety information posted in restaurant kitchens can improve meal safety.” Source: Chapman, Benjamin; Eversley, Tiffany; Fillion, Katie; MacLaurin, Tanya; Powell, Douglas. Assessment of Food Safety Practices of Food Service Food Handlers (Risk Assessment Data): Testing a Communication Intervention (Evaluation of Tools). Journal of Food Protection®, Volume 73, Number 6, June 2010, pp. 1101-1107(7). The provincial regulators also suck.

The provincial regulators also suck..jpg) A related story

A related story