Elizabeth Weise writes in tomorrow’s USA Today that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has asked state and local health officials to focus their investigative efforts on items commonly used in the production of fresh salsa, particularly that made in local restaurants.

Salsas are typically made with tomatoes, onions, jalapeños, garlic and cilantro. They can also include tomatillos and other produce.

Salsas are typically made with tomatoes, onions, jalapeños, garlic and cilantro. They can also include tomatillos and other produce.

The focus does not involve commercially produced salsas. Salsas purchased in cans, jars or plastic containers in the refrigerated section of the supermarket are not being investigated. Fresh-made salsas only, prepared in the home or local restaurants, are the focus.

Tomatoes, originally considered the sole source of the outbreak, remain one of the targeted items, investigators say.

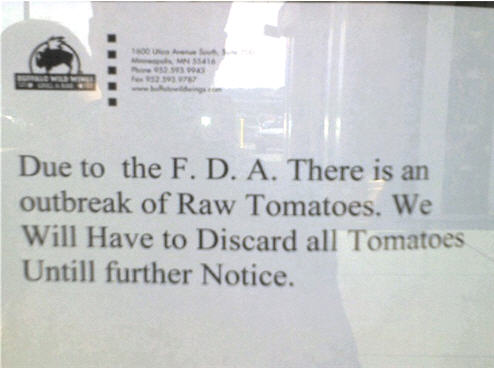

The Food and Drug Administration’s suggestion to avoid red round, Roma and plum tomatoes grown in certain areas is still in effect.

The latest figures for the outbreak are 887 sickened nationwide, with an additional 18 newly confirmed cases. At least 108 people were hospitalized.

Tom Nassif, president and chief executive of Western Growers, which represents produce producers in California and Arizona, said if the outbreak ends up not being associated with tomatoes, growers will have taken a tremendous hit for nothing, and if tomatoes are exonerated, Nassif says growers might ask for financial relief from Congress.

Bill Marler, one of the nation’s leading food-safety attorneys, said the FDA can’t be faulted for acting in the absence of a "smoking tomato" laced with the salmonella bacteria, stating, "Should they have waited until they knew exactly what it was? Well, whose side do they want to come down on: the side of public health and kids or the produce industry?"

I wrote something similar regarding the actions of Ontario government officials after the 1996 cyclospora outbreak (was it California strawberries, no it was Guatemalan raspberries) in the book, Risk and Regulation.

"Once epidemiology identifies a probable link, health officials have to decide whether it makes sense to warn the public. In retrospect, the decision seems straightforward, but there are several possibilities that must be weighed at the time. If the Ontario Ministry of Health decided to warn people that eating imported strawberries might be connected to Cyclospora infection, two outcomes were possible: if it turned out that strawberries are implicated, the ministry has made a smart decision, warning people against something that could hurt them; if strawberries were not implicated, then the ministry has made a bad decision with the result that strawberry growers and sellers will lose money and people will stop eating something that is good for them. If the ministry decides not to warn people, another two outcomes are possible: if strawberries were implicated, then the ministry has made a bad decision and people may get a parasitic infection they would have avoided had they been given the information (lawsuits usually follow); if strawberries were definitely not implicated then nothing happens, the industry does not suffer and the ministry does not get in trouble for not telling people."

I’ll have more to say about this tomorrow.

It was the strongest indication to date by the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that weeks of focus on tomatoes as the culprit may have been a mistake, something that state health officials and other scientists increasingly fear.

It was the strongest indication to date by the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that weeks of focus on tomatoes as the culprit may have been a mistake, something that state health officials and other scientists increasingly fear..jpg) Robert Tauxe, deputy director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s division of foodborne diseases, said CDC launched a new round of interviews over the weekend, adding,

Robert Tauxe, deputy director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s division of foodborne diseases, said CDC launched a new round of interviews over the weekend, adding,.jpg) If not tomatoes, what else? "Something that people find difficult to remember but which is always served with tomatoes," says Tauxe.

If not tomatoes, what else? "Something that people find difficult to remember but which is always served with tomatoes," says Tauxe. The number of ill persons identified in each state is as follows: Arkansas (10 persons), Arizona (39), California (10), Colorado (8), Connecticut (4), Florida (1), Georgia (18), Idaho (3), Illinois (78), Indiana (11), Kansas (14), Kentucky (1), Maine (1), Maryland (25), Massachusetts (18), Michigan (4), Minnesota (2), Missouri (12), New Hampshire (3), Nevada (4), New Jersey (4), New Mexico (85), New York (25), North Carolina (5), Ohio (6), Oklahoma (19), Oregon (7), Pennsylvania (6), Rhode Island (3), Tennessee (6), Texas (342), Utah (2), Virginia (22), Vermont (1), Washington (4), Wisconsin (6), and the District of Columbia (1).

The number of ill persons identified in each state is as follows: Arkansas (10 persons), Arizona (39), California (10), Colorado (8), Connecticut (4), Florida (1), Georgia (18), Idaho (3), Illinois (78), Indiana (11), Kansas (14), Kentucky (1), Maine (1), Maryland (25), Massachusetts (18), Michigan (4), Minnesota (2), Missouri (12), New Hampshire (3), Nevada (4), New Jersey (4), New Mexico (85), New York (25), North Carolina (5), Ohio (6), Oklahoma (19), Oregon (7), Pennsylvania (6), Rhode Island (3), Tennessee (6), Texas (342), Utah (2), Virginia (22), Vermont (1), Washington (4), Wisconsin (6), and the District of Columbia (1). The marked increase in reported ill persons since the last update is not thought to be due to a large number of new infections. The number of reported ill persons increased mainly because some states improved surveillance for Salmonella in response to this outbreak and because laboratory identification of many previously submitted strains was completed. In particular, one new state, Massachusetts reported ill persons.

The marked increase in reported ill persons since the last update is not thought to be due to a large number of new infections. The number of reported ill persons increased mainly because some states improved surveillance for Salmonella in response to this outbreak and because laboratory identification of many previously submitted strains was completed. In particular, one new state, Massachusetts reported ill persons.

“… even use fertilizer that comes from the ground rather than a store. Their fertilizers are made up of layers of manure, weeds and hay.

“… even use fertilizer that comes from the ground rather than a store. Their fertilizers are made up of layers of manure, weeds and hay. Meanwhile, I got to make more friends by telling

Meanwhile, I got to make more friends by telling  But it’s not so easy. I’ve asked questions for years, and only rarely have received adequate responses. Most are of the it’s-local-it’s-safe or trust-me genre of food pornography, and, like most pornography, it’s fun to watch for awhile but gets really boring.

But it’s not so easy. I’ve asked questions for years, and only rarely have received adequate responses. Most are of the it’s-local-it’s-safe or trust-me genre of food pornography, and, like most pornography, it’s fun to watch for awhile but gets really boring. An epidemiologic investigation comparing foods eaten by ill and well persons has identified consumption of raw tomatoes as the likely source of the illnesses. The specific type and source of tomatoes is under investigation; however, the data suggest that illnesses are linked to consumption of raw red plum, red Roma, or round red tomatoes, or any combination of these types of tomatoes, and to products containing these raw tomatoes.

An epidemiologic investigation comparing foods eaten by ill and well persons has identified consumption of raw tomatoes as the likely source of the illnesses. The specific type and source of tomatoes is under investigation; however, the data suggest that illnesses are linked to consumption of raw red plum, red Roma, or round red tomatoes, or any combination of these types of tomatoes, and to products containing these raw tomatoes. We left Quebec City at 9 a.m. last Friday. National Public Radio Science Friday wanted me as a guest, and so did CNN. By 3:30 pm, we were in nowhere southwestern Ontario and I had to call the NPR studio — and they insisted on a landline.

We left Quebec City at 9 a.m. last Friday. National Public Radio Science Friday wanted me as a guest, and so did CNN. By 3:30 pm, we were in nowhere southwestern Ontario and I had to call the NPR studio — and they insisted on a landline..jpg)

To protect the produce, it is essential that safety guidelines are followed, beginning on the farm.

To protect the produce, it is essential that safety guidelines are followed, beginning on the farm.