The Kansas City Star published a couple of highly critical articles about U.S. beef and safety over the weekend.d

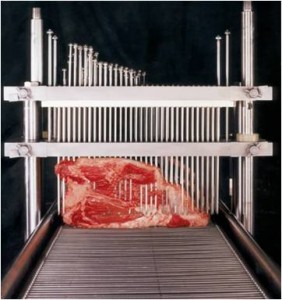

A key component was the issue of needle-tenderized beef and I agree, the lack of information about whether meat is needle-tenderized is frustrating, even for those with a PhD in food science.

Many times over the years, I’ve asked industry and retail food safety leaders, what proportion of the beef you sell is needle-tenderized, only to be met with silence or a  conversational diversion.

conversational diversion.

Some leadership.

Excerpts below; the full stories are worth a read.

Three years ago, at age 87, Margaret Lamkin was, according to the Star, forced to wear a colostomy bag for the rest of her life after a virulent meat-borne pathogen destroyed her colon and nearly killed her.

What made her so sick? A medium-rare steak she ate nine days earlier at an Applebee’s restaurant.

Lamkin, like most consumers today, didn’t know she had ordered a steak that had been run through a mechanical tenderizer. In a lawsuit, Lamkin said her steak came from National Steak Processors Inc., which claimed it got the contaminated meat from a U.S. plant run by Brazilian-based JBS — the biggest beef packer in the world.

“You trust people, trust that nothing is going to happen,” Lamkin said, “but they (beef companies) are mass-producing this and shoveling it into us.”

The Kansas City Star investigated what the industry calls “bladed” or “needled” beef, and found the process exposes Americans to a higher risk of E. coli poisoning than cuts of meat that have not been tenderized.

The process has been around for decades, but while exact figures are difficult to come by, a 2008 USDA survey showed that more than 90 percent of beef producers are using it on some cuts.

Mechanically tenderized meat — which usually isn’t labeled — is increasingly found in grocery stores, and a vast amount is sold to family-style restaurants, hotels and group homes. In many cases, grocery stores don’t even know the meat has been tenderized.

The American Meat Institute, an industry lobbying group, has defended the product as safe, but institute officials recently said they can’t comment further until they see the results of a pending risk assessment by the meat safety division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Although blading and injecting marinades into meat add value for the beef industry, that also can drive pathogens — including the E. coli O157:H7 that destroyed Lamkin’s colon — deeper into the meat.

If it isn’t cooked sufficiently, people can get sick. Or die.

There have been several USDA recalls of the product since at least 2000, and a Canadian recall in October included mechanically tenderized steaks imported into the United States.

In a 2010 letter to the USDA, the American Meat Institute noted eight recalls between 2000 and 2009 that identified mechanically tenderized and marinated steaks as the culprit. Those recalls sickened at least 100 people.

The Star examined the largest beef packers including the big four— Tyson Foods of Arkansas, Cargill Meat Solutions of Wichita, National Beef of Kansas City and JBS USA  Beef of Greeley, Colo. — as well as the network of feedlots, processing plants, animal drug companies and lobbyists who make up the behemoth known as Big Beef.

Beef of Greeley, Colo. — as well as the network of feedlots, processing plants, animal drug companies and lobbyists who make up the behemoth known as Big Beef.

What The Star found is an increasingly concentrated industry that mass-produces beef at high speeds in mega-factories that dot the Midwest, where Kansas City serves as the “buckle” of the beef belt. It’s a factory food process churning out cheaper and some say tougher cuts of meat that can cause health problems. The Star’s other key findings:

• Large beef plants, based on volume alone, contribute disproportionately to the incidence of meat-borne pathogens.

• Big Beef and other processors are co-mingling ground beef from many different cattle, some from outside the United States, adding to the difficulty for health officials to track contaminated products to their source. The industry also has resisted labeling some products, including mechanically tenderized meat, to warn consumers and restaurants to cook it thoroughly.

• Big Beef is injecting millions of dollars of growth hormones and antibiotics into cattle, partly to fatten them quickly for market. But many experts believe that years of overuse and misuse of such drugs contributes to antibiotic-resistant pathogens in humans, meaning illnesses once treated with a regimen of antibiotics are much harder to control.

• Big Beef is using its political pull, public relations campaigns and the supportive science it sponsors to influence federal dietary guidelines and recast steaks and burgers as health foods people can eat every day. It even persuaded the American Heart Association to certify beef as “heart healthy.”

Big Beef, industry critics contend, has grown too big for Big Government to lasso.

Indeed, the U.S. beef industry is twice as concentrated as it was when President Teddy Roosevelt took on and beat the old Armour, Swift, Cudahy and Morris beef trust in the early 1900s. The big four packers today slaughter 87 percent of all heifers and steers.

“Roosevelt,” remarked Montana rancher Dan Teigen, “would be spinning in his saddle.”

Thanks in large part to the Midwest’s grassy plains and ample row crops, the United States produces 26 billion pounds of beef a year from 34 million cattle — more than any other country.

Four of the seven largest beef slaughterhouses — each capable of killing 6,000 head a day — are in Kansas, which leads the nation in meat processing.

The big slaughterhouses are among the last vestiges of old-line American manufacturing, except that they take things apart instead of putting them together. Meat slaughter and processing employs 260,000 people, and Big Beef’s highly efficient plants supply a large share of those jobs in the Midwest.

As a result, despite recent price hikes, beef costs less in the United States than anywhere in the world. It has become America’s crude oil — in high demand worldwide, including  faraway lands where a newly-minted middle class is acquiring a taste for more expensive protein.

faraway lands where a newly-minted middle class is acquiring a taste for more expensive protein.

James Marsden, a food safety professor at Kansas State University, agreed that the industry is improving, but said it could do a better job with mechanically tenderized steaks.

“E. coli is impossible to eradicate from beef cattle,” he said. But a key to eliminating it in mechanically tenderized steaks is to use “interventions” such as spraying lactic acid on the meat to reduce or eliminate surface contamination. Some companies do that, he said, but the USDA does not require it.

For years, the USDA has urged the industry to voluntarily label such products, but found in 2008 that few beef plants were doing so. Costco is among stores that do label such products as being bladed. Those labels advise consumers that “for your safety USDA recommends cooking to a minimum temperature of 160 degrees.”

Not labeling mechanically tenderized beef jeopardizes consumers and puts health officials at a disadvantage if there’s an outbreak, experts said.

American Meat Institute President J. Patrick Boyle responded to the Star articles by stating:

“Nine months ago, we were asked to participate in an in-depth story for the Kansas City Star about the beef industry. We were told that the paper would examine the industry through the eyes of four beef packers. The industry has recognized the need to communicate and to be more transparent. That’s exactly what we all did.

By our count, reporter Mike McGraw benefitted from visits to two large packing plants, at least one feedlot and a processing plant. He was allowed to bring cameras. This was truly unprecedented access to the industry and its operations. Industry executives provided countless interviews. AMI did its best to answer any question posed and even plotted charts when asked for additional data presented in ways that we didn’t have readily available. Our colleagues at other associations responded similarly.

We believed that by cooperating, he would see what we saw: a beef industry that provides the safest and most affordable beef supply in the world. We know that we cannot rest on the progress achieved and must always strive to do better, but we find it impossible to reconcile the conclusions reached by the Star with data from data from CDC, FSIS, OSHA and other agencies.

The end result was a huge disappointment. Perhaps the most telling aspect in the series is his pejorative use of the term Big Beef (capitalized) throughout the pieces and his references to Big Government (also capitalized). “

Safest food supply in the world isn’t going to convince anybody.

.jpg) one is saying how common.

one is saying how common. That was two weeks ago.

That was two weeks ago.