Amy is a carnivore. First time I went to dinner at her place, almost four years ago, we couldn’t decide what to eat. Eventually, Amy said, let’s go to the supermarket, get a couple of steaks, and grill at home.

I was in love.

I was in love.

Amy’s grill (right) served us well, but the years took its toll. So we splurged and got a new BBQ – the Weber Genesis — which I used for the first time last night. Whenever we get a new car, or grill, or pretty much anything, since I insist on owning things for 10 years until they are completely spent, I marvel at the technological advances. It was awesome.

We grill meat and vegetables pretty much every day. And maybe it’s not so cool after last weeks tragic story of E. coli O157:H7 victim Stephanie Smith, but we eat hamburgers – make them at home from ground beef and turkey.

The news is confusing: The N.Y. Times feature by Michael Moss that started the latest round of confusion said hamburger trim was mixed together from all sorts of places and no one wanted to test for E. coli O157:H7 (that’s what happens with a zero tolerance policy; don’t test, don’t tell). Subsequently the Times said in an editorial that the only way to be safe was to cook hamburger to shoe leather, and former Centers for Disease Control-type, Richard Bessler told Diane Sawyer on Good Morning America the only way to cook meat safely is to "cook it to the point where most people wouldn’t want to eat it."

Former U.S. Department of Agriculture Undersecretary for Food Safety, Richard Raymond, responded on his blog that the Times story simplified a few things about testing and mixing, and that, “raw meat and raw poultry should not be considered to be pathogen free—ever.”

Former U.S. Department of Agriculture Undersecretary for Food Safety, Richard Raymond, responded on his blog that the Times story simplified a few things about testing and mixing, and that, “raw meat and raw poultry should not be considered to be pathogen free—ever.”

Then yesterday, the Minnesotans, home of Cargill, tried to poke a few more holes in the Times story.

Craig Hedberg, professor of environmental health sciences at the University of Minnesota, said,

“Testing of product, either raw materials or finished products, is something that has limited usefulness. We can’t test every square inch of an animal’s carcass to see if there’s bacteria present … it just would be too expensive.”

I’m not sure who we is, and playing cost off against human health is never a good tactic.

Ryan Cox, professor of meat science at the University of Minnesota said,

“If you were to go into a modern meat facility, it looks very similar to a surgical suite in a hospital.”

Especially with the sick people.

Cox explained that meat industry practices are so stringently regulated that “to infer in some way that we have an unsafe system would be certainly an error.”

(1).jpg) Pete Nelson , who spent 35 years running a USDA-inspected facility, defended the multiple sourcing used by large processing plants. He cited the need for a steady supply of beef in case an individual slaughterhouse is not able to deliver on time, as well as the need for a variety of meats to ensure consistency. …

Pete Nelson , who spent 35 years running a USDA-inspected facility, defended the multiple sourcing used by large processing plants. He cited the need for a steady supply of beef in case an individual slaughterhouse is not able to deliver on time, as well as the need for a variety of meats to ensure consistency. …

Both Nelson and Cox said consumers have an important role in food safety, especially in the handling and cooking of raw meats.

“We both agree on the fact that there really wouldn’t have been much of a story to begin with, particularly with the instance [The New York Times] cited with the food sickness, if the product had been cooked to the correct internal temperature.

Ouch. Blame the consumer. USDA stopped that in 1994.

Cross-contamination is a serious issue, as repeatedly pointed out on this blog and in our research, and that’s why pathogen loads have to be reduced as much as possible before entering a further processing plant, a restaurant, a grocery store or someone’s kitchen. And then, as Raymond says, never assume meat – or any raw food – is pathogen free. Same with animals. Those 90 kids that got sick with E. coli O157:H7 at a petting zoo in the U.K. weren’t dealing with meat from different sources.

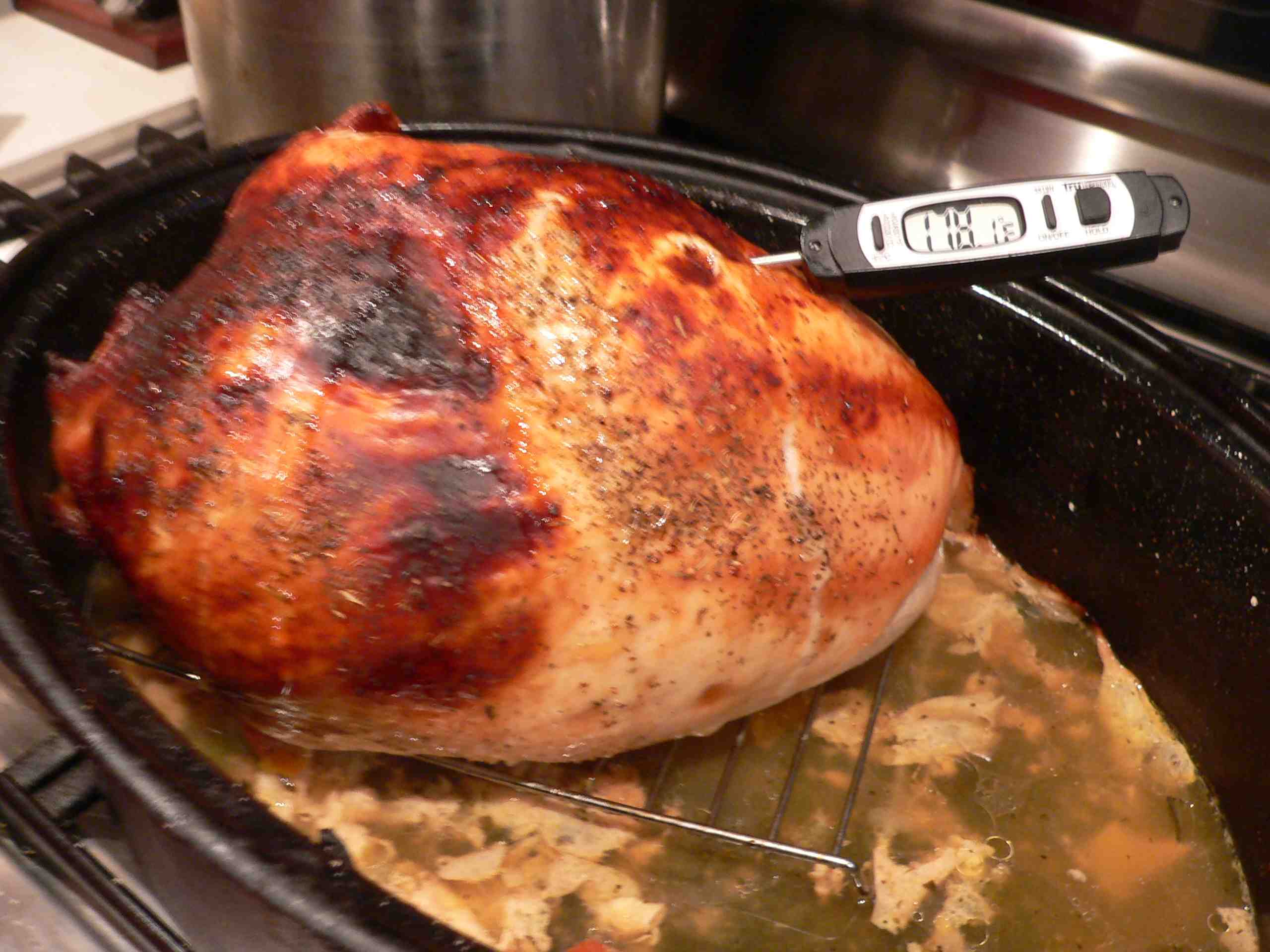

And no one has to cook to shoe leather. Meat thermometers can help, and stick it in until 160F for hamburger.

Our steaks were a delicious 125F, climbing to about 135F over time.

I’ve packed a lot of lunches over a lot of years and 5 daughters. Didn’t use ice packs. Did use a variety of cooler bags given out as swag at conferences that would keep things cool.

I’ve packed a lot of lunches over a lot of years and 5 daughters. Didn’t use ice packs. Did use a variety of cooler bags given out as swag at conferences that would keep things cool.

thermometer in his front pocket, which I asked to borrow for the interview. One of the PR types said something like, you can’t go on TV and talk about using thermometers, we have enough trouble getting Australians to store food in the fridge, which is largely used for beer.

thermometer in his front pocket, which I asked to borrow for the interview. One of the PR types said something like, you can’t go on TV and talk about using thermometers, we have enough trouble getting Australians to store food in the fridge, which is largely used for beer. Willard showed up in a cameo in yet another movie – the guy’s everywhere – and I was telling her about this wildly satirical talk show featuring Willard as sidekick Jerry Hubbard, and host Barth Gimble, played by Martin Mull.

Willard showed up in a cameo in yet another movie – the guy’s everywhere – and I was telling her about this wildly satirical talk show featuring Willard as sidekick Jerry Hubbard, and host Barth Gimble, played by Martin Mull. When it comes to offering bad food safety advice,

When it comes to offering bad food safety advice,  What better occasion to try out alleged

What better occasion to try out alleged  And I didn’t take pictures of Thursday’s dinner, but Top Chef on Wed. night also struggled with lamb, and none of the hot-shot chefs could agree on how to define medium-rare lamb.

And I didn’t take pictures of Thursday’s dinner, but Top Chef on Wed. night also struggled with lamb, and none of the hot-shot chefs could agree on how to define medium-rare lamb.  The lamb shoulder roast we had last night was cooked to 140F.

The lamb shoulder roast we had last night was cooked to 140F.  The problem with such refrigerated, ready-to-eat foods is listeria, the bacterium that’s everywhere and grows at refrigerator temperatures.

The problem with such refrigerated, ready-to-eat foods is listeria, the bacterium that’s everywhere and grows at refrigerator temperatures.  Researchers from USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS) in Wyndmoor, PA, found greater inactivation rates of Listeria monocytogenes occurred in samples processed at higher temperatures and in samples containing higher concentrations of salt and smoke compound. The inactivation rate increased tenfold when the temperature increased by 5° C, indicating that smoking temperature is a main factor affecting the inactivation of the pathogen. In addition, salt and smoke compounds also contribute to the inactivation effect.

Researchers from USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS) in Wyndmoor, PA, found greater inactivation rates of Listeria monocytogenes occurred in samples processed at higher temperatures and in samples containing higher concentrations of salt and smoke compound. The inactivation rate increased tenfold when the temperature increased by 5° C, indicating that smoking temperature is a main factor affecting the inactivation of the pathogen. In addition, salt and smoke compounds also contribute to the inactivation effect. .jpg) We’ve been saying for a couple of years that water temperature is not a critical factor

We’ve been saying for a couple of years that water temperature is not a critical factor(1).jpg)

I was in love.

I was in love.(1).jpg) Pete Nelson , who spent 35 years running a USDA-inspected facility, defended the multiple sourcing used by large processing plants. He cited the need for a steady supply of beef in case an individual slaughterhouse is not able to deliver on time, as well as the need for a variety of meats to ensure consistency. …

Pete Nelson , who spent 35 years running a USDA-inspected facility, defended the multiple sourcing used by large processing plants. He cited the need for a steady supply of beef in case an individual slaughterhouse is not able to deliver on time, as well as the need for a variety of meats to ensure consistency. … The Food Standards Agency today published the findings of a new survey testing for campylobacter and salmonella in chicken on sale in the U.K.

The Food Standards Agency today published the findings of a new survey testing for campylobacter and salmonella in chicken on sale in the U.K..jpg)

While sitting around today and watching some college football I started to think a bit more about my dad’s question and dug up some

While sitting around today and watching some college football I started to think a bit more about my dad’s question and dug up some  But I’m getting some payback now as she enters the third hour of her nap, and decided a homemade hamburger with grilled corn and salad would make a decent lunch for myself. Coupled with the season premier of Californication on the recorderer, I was set.

But I’m getting some payback now as she enters the third hour of her nap, and decided a homemade hamburger with grilled corn and salad would make a decent lunch for myself. Coupled with the season premier of Californication on the recorderer, I was set..jpg) "When they start to come out of the top of the burger, it’s medium. When the juices that have oozed out of the top get cooked (stop looking red and become a bit more clear), it’s medium-well."

"When they start to come out of the top of the burger, it’s medium. When the juices that have oozed out of the top get cooked (stop looking red and become a bit more clear), it’s medium-well."