Dr. Donald W. Schaffner, extension specialist in food science and professor at Rutgers University writes in this guest blog post:

A colleague emailed me a link the other day and asked for my opinion. He’s a raw milk advocate, so I was curious. The title was intriguing — The Complex Origins of Food Safety Rules, Yes, You Are Overcooking Your Food, a chapter precis from Modernist Cuisine — and one of the author’s names was familiar; famous in a famous Internet nerd sort of way. Sure enough Nathan Myhrvold is a famous nerd. And I do love me those Internet nerds. So, as I often do, I saved the link to read later. As I started reading  several things impressed me, most notably, a rather clear description of D-values in an article written for the general public. Unfortunately, after that the article began to fall apart. I marked up a pdf copy on my iPad and emailed the comments off to my colleague.

several things impressed me, most notably, a rather clear description of D-values in an article written for the general public. Unfortunately, after that the article began to fall apart. I marked up a pdf copy on my iPad and emailed the comments off to my colleague.

The next day, I was still thinking about the article. I emailed Doug to let him know I was interested in blogging about it. He was encouraging, and shared with me what he’d written already, which included a clip of Myrvold’s appearance on the always entertaining Colbert Report. Essentially, I agreed with Doug, so if you are one of those TL;DR blog readers, you can stop now and get back to work.

The book chapter has a light and breezy style, and who doesn’t love that, but in their attempt to be conversational, the authors miss the mark.

"Right away, you can see that decisions about pathogen-reduction levels are inherently arbitrary because they require guessing the initial level of contamination."

Arbitrary is defined as, "Based on random choice or personal whim, rather than any reason or system" and while I’ll be the first to note that food safety standards often lack consistency, they are not random. The problem is historical standards were developed at a time when understanding of risk, including microbial risk, was rudimentary. Quantitative microbial risk assessment applied to food has only been around for 10-15 years, while food safety laws have evolved over centuries. As a former CTO (nerd speak for chief technology officer) for a company that had to deal with backward compatibility of Microsoft operating systems (operating systems that I not longer use – sorry, I’m that guy), you’d think Myhrvold might have a better  appreciation of that fact. Further, it’s not a matter of "guessing" the initial contamination level, it’s a matter of understanding that the initial contamination level in foods is variable, and for any food in question, is unknowable without testing that food for the presence of pathogens. As a physicist, Myhrvold should understand that we can’t observe a system (test for pathogens) without disturbing its state (have nothing left to cook).

appreciation of that fact. Further, it’s not a matter of "guessing" the initial contamination level, it’s a matter of understanding that the initial contamination level in foods is variable, and for any food in question, is unknowable without testing that food for the presence of pathogens. As a physicist, Myhrvold should understand that we can’t observe a system (test for pathogens) without disturbing its state (have nothing left to cook).

Myhrvold and his cookery co-authors do make good points that show a level of understanding sometimes lacking in food safety professionals that were asleep during the lecture on D-values. They are completely correct that, "No matter what the standard is, if the food is highly contaminated, it might still be unsafe" after cooking. Because bacterial survival during cooking is a probability game, if a food is contaminated at the low level, it might contain pathogens after "proper" cooking just by bad luck alone.

Myhrvold et al. state "To compensate for this inherent uncertainty, food safety officials often base their policies on the so-called worst-case scenario," yet inherently contradict themselves by stating, "There are no guarantees and no absolutes.” Instead, food safety policy makers base their recommendations on conservative assumptions. Exactly how conservative to make those assumptions, and what other factors come in to play, is a risk management discussion, and not a discussion solely based on science.

One of the problems with Myhrvold and his co-authors is while they might understand the mathematics of microbial destruction, as well as the culinary arts, their understanding of food microbiology is sorely lacking. They talk about, "required pathogen reductions … range from a 4D drop for some extended-shelf-life refrigerated foods… to a 12D drop for canned food, which must last for years on the shelf" and they imply from this, that somehow these regulations are flawed. As any food microbiologist knows (even the ones that slept through the lecture on D-values), the risks posed by extended-shelf-life refrigerated foods are quite different that the risks posed by canned food. The target pathogen in extended-shelf-life refrigerated foods is likely Listeria monocytogenes or perhaps  nonproteolytic Clostridium botulinum, while the target for canned foods is proteolytic Clostridium botulinum for safety and Clostridium sporogenes for spoilage.

nonproteolytic Clostridium botulinum, while the target for canned foods is proteolytic Clostridium botulinum for safety and Clostridium sporogenes for spoilage.

Myhrvold and friends have a complete lack of citations and references. For a book about the art and science of cooking, some degree of citation back to the literature or the relevant regulations would be appreciated. Some of the best writing being done today, whether long form or short recognizes the need to cite primary sources. This is hardly new, as one of my favorite science writers of all time (SJG RIP) pointed out more than 20 years ago.

For example Myhrvold et al. talk about something called "General FDA cooking recommendations" and note that "fresh food are set to reach a reduction level of 6.5D," and from the context I’m going to google-guess they mean the FDA model food code recommendations for cooking to eliminate Salmonella. In that same paragraph, Myhrvold et al. state that "Many nongovernmental food safety experts believe this level is too conservative." While this might be true, I have no way to check this supposed fact.

Myhrvold et al. go on to talk about "An expert advisory panel… 2003 report [that] questioned the FSIS Salmonella reduction standards for ready-to-eat poultry and beef products." I’m pretty sure they mean the 2003 book entitled Scientific Criteria to Ensure Safe Food. I was part of that National Academy of Sciences committee that authored the book, and yes, we did call out the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety Inspection Service for "an excessively conservative performance standard.” We did this on page 9 (executive summary), in the body of the book on page 161 and on page 262 on our summary. The particular quote that I’d like to mention from the book however appears on page 148. Here we say, "Regulatory agencies need to properly set performance standards. This is a balancing act between setting a highly conservative performance standard and setting an excessively tolerant one." So, yes, while we did call out FSIS in that particular instance, we also recognize that there is a balance to be struck.

Myhrvold et al. make the statement that "in food safety, cross-contamination is often the weakest link." While it’s true that cross-contamination is being increasingly realized as a means by which foodborne pathogens can cause disease, a research effort to which we have contributed, I’m curious how Myhrvold et al. determine that it is often the weakest link. They go on to state, "One powerful criticism of food safety standards is that they protect against unlikely worst-case scenarios yet do not address the more likely event of cross-contamination." While it’s true that a cooking standard does not offer any protection against cross-contamination, other standards may reduce cross-contamination risk. For example, that 2003 book, Scientific Criteria to Ensure Safe Food, does note that "the Norwegian Agriculture Department is testing broiler flocks for Campylobacter and requiring positive flocks to be slaughtered after  negative flocks to avoid cross-contamination at the plant; carcasses from positive flocks are then cooked or frozen under supervision," page 49, in case you’d like to check my facts. Check page 51, same book, and you’ll learn than "In Denmark… pork herds that have a high prevalence of Salmonella… are slaughtered separately from animals that come from herds with a low prevalence of Salmonella in order to avoid cross-contamination during slaughter and dressing; they are also used only in cooked products."

negative flocks to avoid cross-contamination at the plant; carcasses from positive flocks are then cooked or frozen under supervision," page 49, in case you’d like to check my facts. Check page 51, same book, and you’ll learn than "In Denmark… pork herds that have a high prevalence of Salmonella… are slaughtered separately from animals that come from herds with a low prevalence of Salmonella in order to avoid cross-contamination during slaughter and dressing; they are also used only in cooked products."

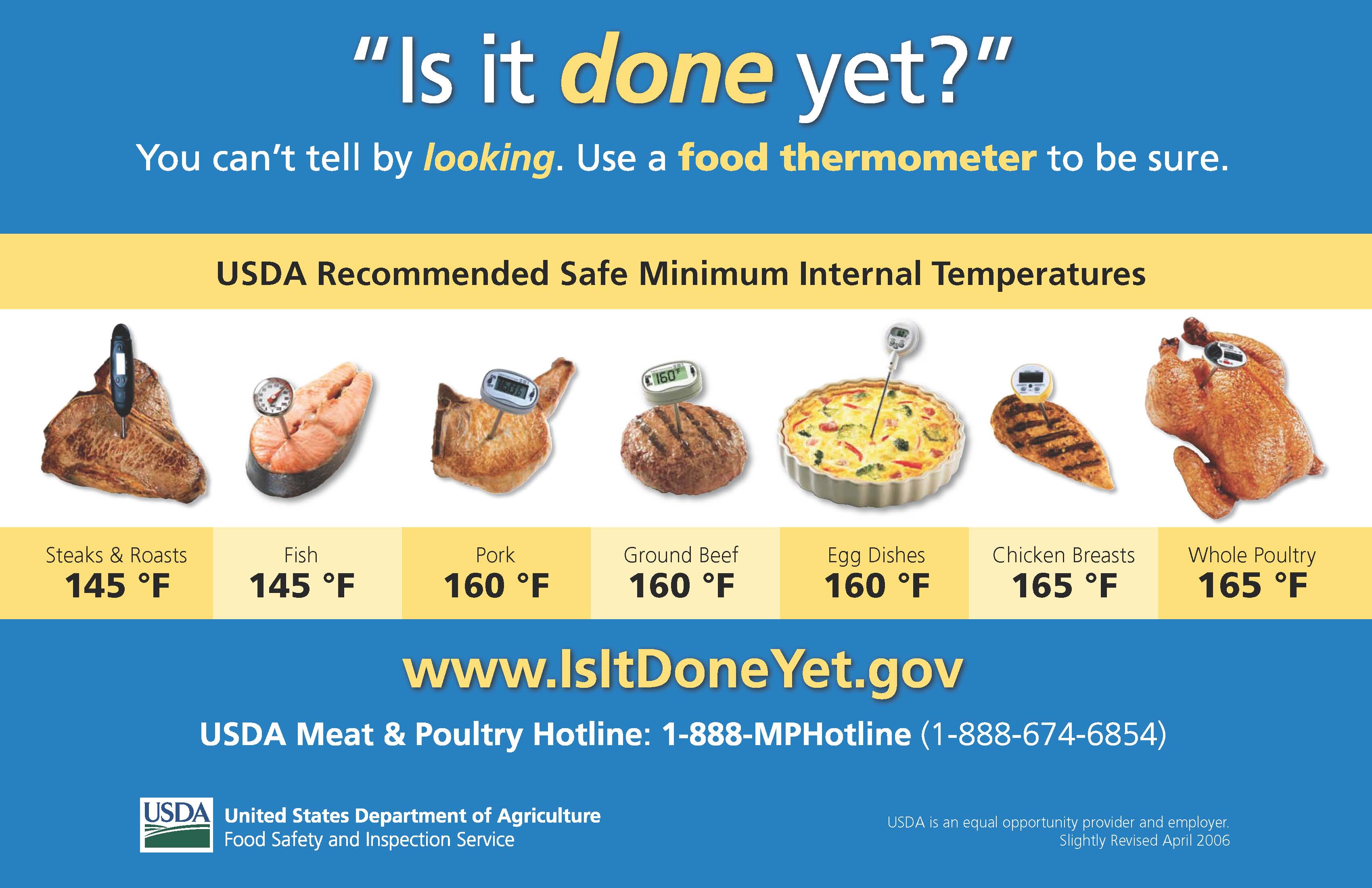

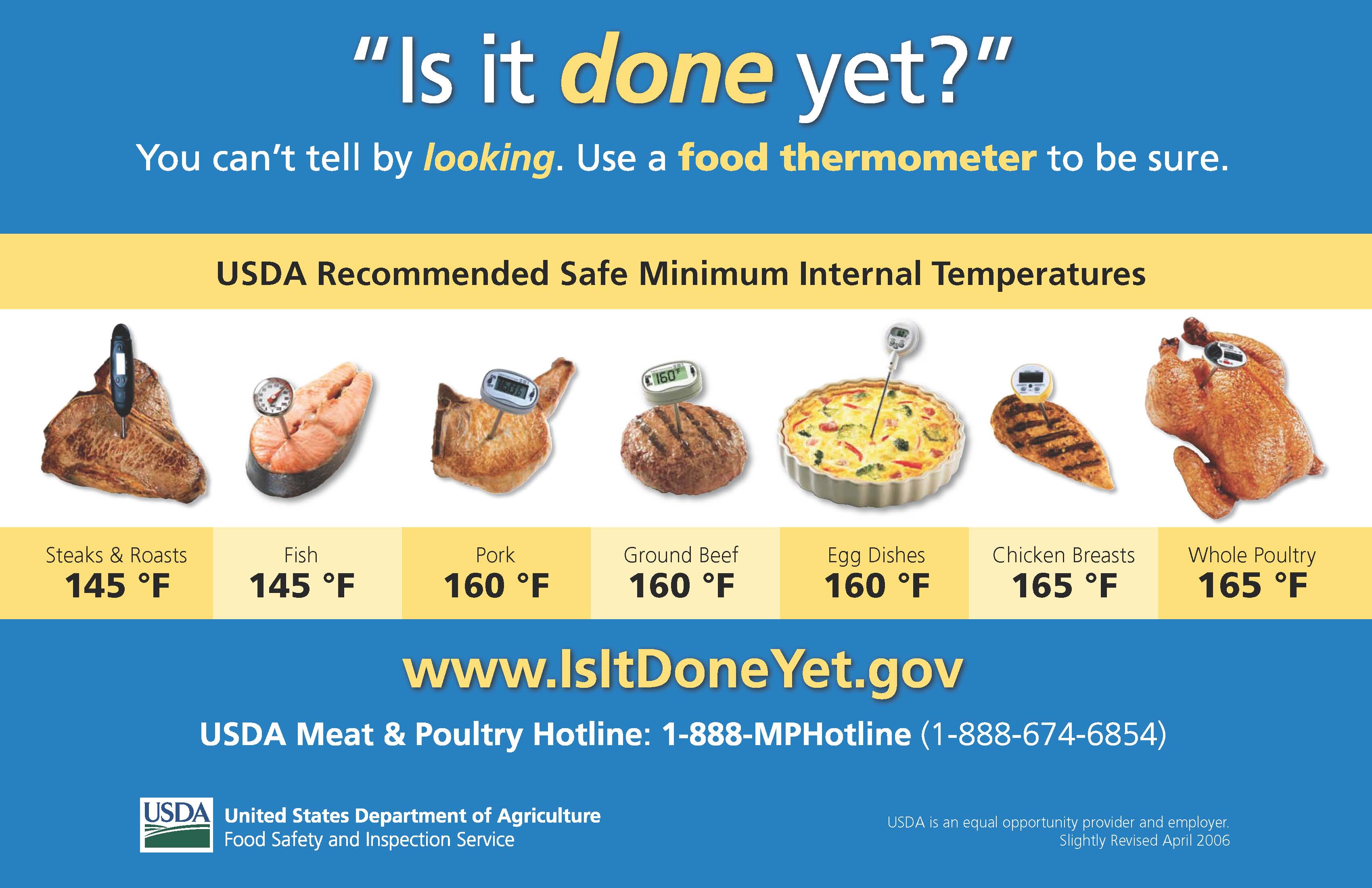

Myhrvold et al. call out "Another conservative tactic used by health officials" which is "to artificially raise the low end of a recommended temperature range." Myhrvold himself demonstrates this fact in his appearance on the Colbert Report where he feeds Stephen pastrami cooked for 72 hours at 130 F. However, I disagree with the implication that this is somehow a vast conspiracy designed to insure people eat overcooked foods. A quick check of the USDA FSIS Appendix A guidelines shows that USDA does indicate that meat processors can cook meat at 130 F and that a 7D cook for Salmonella is reached in 121 minutes. Myhrvold et al. go on to state that “Most food pathogens can be killed at temperatures above 50 degrees C / 120 degrees F, yet food safety rules tend to require temperatures much higher than that.” The authors further state, “Technically, destruction of Salmonella can take place at temperatures as low as 48 degrees C / 120 degrees F given enough time” and “There is no scientific reason to prefer any one point on the reduction curve.”

This is where the authors’ complete lack of food microbiology experience shines through. They provide no proof of their assertion that most pathogens are killed above 120 F, but here’s the rub: some pathogens, including those like C. perfringens that might have been present in Colbert’s pastrami actually start to multiply at temperatures between 120 and 130 F, so in fact there is a very good reason to use cooking temperatures above 130 F. Hopefully Myhrvold used a calibrated thermometer, we don’t want to see Stephen on the celebrity food poisoning list.

Myhrvold et al. rail about "unscientific food safety standards." Any such standard is a policy or risk management decision. While it’s good to have science or risk-based standards, there is no such thing as a “scientific standard” because any standard, guideline or criteria must consider far more than the science.

Myhrvold et al. further rant against “public health authorities” in what I assume was the 2006 E. coli O157:H7 outbreak in fresh spinach claiming that they “told consumers, retailers, and restaurants to throw out all spinach, often directly stating in public announcements that it could not be made safe by cooking it.” According to my search I don’t see any Food and Drug Administration statement about cooking at all. FDA did “advise consumers to not eat fresh spinach or fresh spinach-containing products until further notice.” A search of the U.S. Centers of Disease Control found this advice for consumers: “E. coli O157:H7 in spinach can be killed by cooking at 160 Fahrenheit for 15 seconds.”

Myhrvold et al. note "The authorities must have decided that the benefits of avoiding multiple accidental deaths far outweighed the costs of simply tossing out all spinach," and I think they are probably correct. If you’d like  to read a thoroughly researched discussion of the outbreak (with actual references!) focusing on what did consumers know, where did they get that information, and what did they do in response to the advisories issued by the FDA warning them not to eat fresh spinach, this article from my colleagues at Rutgers University would be a good place to start.

to read a thoroughly researched discussion of the outbreak (with actual references!) focusing on what did consumers know, where did they get that information, and what did they do in response to the advisories issued by the FDA warning them not to eat fresh spinach, this article from my colleagues at Rutgers University would be a good place to start.

Rather than focus on whether or not advice was provided about cooking, if one were to criticize “public health authorities,” a better place to start might be whether any recall at all was needed. A review of the epidemic curve shows that by the time of the first FDA announcement on September 14, 2006, the outbreak was essentially over. In defense of my hard working colleagues in public health, as I once heard Paul Mead say, “Food safety recalls are always either too early or too late. If you’re right, it’s always too late. If you’re wrong, it’s always too early.” At least I think I heard him say that. The only source for that quote that I could find on the Internet is me.

Myhrvold et al. then move from a discussion about E. coli in spinach to Trichinella in pork, calling the recommendations (which ones? citation please) “ridiculously excessive." While it does appear from the literature that incidence in pigs is declining over time and is generally low, that unlike bacterial pathogens, Trichinella larvae are found in the muscle, not just on the surface. In any event, it appears that a microbial risk assessment is possible and if Myhrvold et al. have completed one, please do submit it for publication, and request me as an editor.

Myhrvold et al. call out, "Cooking standards for chicken, fish, and eggs, as well as rules about raw milk cheeses, all provide examples of inconsistent, excessive, or illogical standards.” Inconsistentcy is to be expected, given that different people developed different standards at different times and for different reasons. Is this a good thing? Probably not. Is it starting to change? I’d say that I’m cautiously optimistic, and kudos to those who are trying to move forward and use risk-based or risk-informed decision making processes.

While it’s true that, “A chef’s livelihood may depend on producing the best taste and texture for customers,” it’s also true that a chef’s livlihood livelihood requires customers that remain alive.

Myhrvold et al. state, “so if that meat were inherently dangerous, we’d certainly know by now.” Barbara Kowalcyk has some idea on the inherent risks from meat, the difference is that she’s actually doing something about it. Myhrvold et al. go on to state, “Scientific investigation has confirmed the practice [eating raw steak] is reasonably safe — almost invariably, muscle interiors are sterile and pathogen free. That’s true for any meat, actually, but only beef is singled out by the FDA." Except some steaks are subject to blade tenderization, a practice that can internalize any pathogens on the surface, so just because it’s an apparently intact piece, doesn’t meant that it’s pathogen free. And FDA doesn’t regulate beef, USDA FSIS has that responsibility. Assuming that Myhrvold et al. didn’t get the name of the agency wrong, then they must be talking about the FDA model food code, which is in fact not a regulation at all but model that “assists food control jurisdictions at all levels of government by providing them with a scientifically sound technical and legal basis for regulating the retail and food service segment of the industry.” And if Myhrvold et al. don’t like what the FDA model code says, they can change it (see below).

Myhrvold et al. note “Traditional cheese-making techniques, used correctly and with proper quality controls, eliminate pathogens without the need for milk pasteurization.” As they themselves have remarked earlier in the chapter, “There are no guarantees and no absolutes.” So it’s not that the French “eliminate pathogens” its just that they reduce pathogens to levels that the French consumer finds acceptable. Myhrvold et al. actually go on to make my point for me when they say "Millions of people safely consume .jpg) raw milk cheese in France, and any call to ban such a fundamental part of French culture would meet with enormous resistance there." This is exactly why it doesn’t come down to science in the end. Science informs, but policy makers then deliberate, considering the science and other factors (including cultural preference), before making a decision.

raw milk cheese in France, and any call to ban such a fundamental part of French culture would meet with enormous resistance there." This is exactly why it doesn’t come down to science in the end. Science informs, but policy makers then deliberate, considering the science and other factors (including cultural preference), before making a decision.

Myhrvold et al. go on to note a variety of issues around raw milk cheeses including standard for import into the U.S., crossing state lines and sale within individual states and the province of Quebec, ending with, "How can these discrepancies among and even within countries persist?" It comes down to politics. And they are right; it is politics, or at least it’s food safety policy. The situation persists in the U.S. because FDA governs interstate commerce, while in-state commerce is the province of the state (or the province) and good policy considers the science, evaluates the risk and then makes a decision that is viable within that geographical boundary. They are absolutely spot on when they say “changing a regulation is always harder than keeping it intact, particularly if the change means sanctioning a new and strange food or liberalizing an old standard.” But change is possible, especially when it’s based on science.

Not content with making misstatements about food microbiology, Myhrvold et al. venture in to epidemiology, noting that many people apparently incorrectly believe “that chicken is the predominant source of Salmonella” and that "In a 2009 analysis by the CDC, Salmonella was instead most closely associated with fruits and nuts, due in part to an outbreak linked to peanut butter in 2006." Foodborne disease attribution is actually kind of complicated and while many Salmonella cases in the U.S. in 2006 might have been due to fruits and nuts, that doesn’t mean that this is always the cases year over year, or that somehow chicken is risk free.

Myhrvold et al. bring things to a close by providing the closest thing to a real citation by mentioning a National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods (NACMCF) publication in the Journal of Food Protection in 2007 where they discover some “amazing admissions” from this panel of “health officials” that at least to my untrained eye looks to be mostly food microbiologists and one biostatistician. I was a member of that committee.

In the U.S. there are no “consumer regulations” that govern how people are to prepare foods in their own homes. If there were such regulations, they wouldn’t be administered by FSIS. Assuming this is a typo and they meant to write “recommendations,” these recommendations are in fact written by USDA FSIS Food Safety Education Staff whose mission is to inform consumers about the importance of safe food handling. The charge to NACMCF was in response to a real problem, as noted in the JFP article. “The questions were generated in response to foodborne illnesses from Salmonella related to the consumption of processed chicken products that appeared to be ready to eat (RTE) but contained poultry that was not ready to eat (NRTE).” And the FSIS staffers listened to our recommendations, reducing the whole muscle instantaneous cooking temperature from 180 F to 165 F, quite an impressive feat to “liberalize an old standard.” And while I’m delighted to learn that apparently “chicken cooked at 58 degrees C /136 degrees F and held there for the recommended time is neither rubbery nor pink,” I’d feel more confident if Myhrvold et al. provided a citation.

I’m all for letting “chefs and consumers be the ones to decide what they would prefer to eat.” I’m a food libertarian. You can eat what you want, whether you are a consumer or a chef, but if you are a chef, and you are cooking for me, I’d prefer that you calibrate your thermometer and that you follow a validated cooking protocol.

It seems that much of what Myhrvold et al. object to are the recommendations in the FDA Model Food Code. The Food Code is developed in a transparent and public process. Details can be found on the Conference for Food Protection Web site. Nathan Myhrvold, are you busy April 13 – 18, 2012? We are always chronically short of consumer representation on each of the three councils. Do you want to add to your already impressive resume? If you come to Indianapolis, Indiana, I’ll buy the beer.

Dr. Donald W. Schaffner is Extension Specialist in Food Science and Professor at Rutgers University. His research interests include quantitative microbial risk assessment and predictive food microbiology. In his free time, he reads blogs on the Internet.

avait été achetée réfrigérée auprès de commerçants et étiquetée « A conserver réfrigérée ». Après avoir conservé la soupe à température ambiante pendant un certain temps avant de la manger, les deux personnes ont développé des symptômes du botulisme.

avait été achetée réfrigérée auprès de commerçants et étiquetée « A conserver réfrigérée ». Après avoir conservé la soupe à température ambiante pendant un certain temps avant de la manger, les deux personnes ont développé des symptômes du botulisme.

medium, and one well done. As one of the chefs uses a tip sensitive digital thermometer to check temperatures, Chef Graham Elliot comments something along these lines – every time he uses the thermometer, he lets those juices flow out.

medium, and one well done. As one of the chefs uses a tip sensitive digital thermometer to check temperatures, Chef Graham Elliot comments something along these lines – every time he uses the thermometer, he lets those juices flow out..jpg)

.jpg) violations. Inspectors didn’t go back last year to check to see if the problems were remedied.

violations. Inspectors didn’t go back last year to check to see if the problems were remedied.(1).jpg) • science and evidence-based;

• science and evidence-based;.jpg)

several things impressed me, most notably, a rather clear description of D-values in an article written for the general public. Unfortunately, after that the article began to fall apart.

several things impressed me, most notably, a rather clear description of D-values in an article written for the general public. Unfortunately, after that the article began to fall apart.  nonproteolytic Clostridium botulinum, while the target for canned foods is proteolytic Clostridium botulinum for safety and Clostridium sporogenes for spoilage.

nonproteolytic Clostridium botulinum, while the target for canned foods is proteolytic Clostridium botulinum for safety and Clostridium sporogenes for spoilage. negative flocks to avoid cross-contamination at the plant; carcasses from positive flocks are then cooked or frozen under supervision," page 49, in case you’d like to check my facts. Check page 51, same book, and you’ll learn than "In Denmark… pork herds that have a high prevalence of Salmonella… are slaughtered separately from animals that come from herds with a low prevalence of Salmonella in order to avoid cross-contamination during slaughter and dressing; they are also used only in cooked products."

negative flocks to avoid cross-contamination at the plant; carcasses from positive flocks are then cooked or frozen under supervision," page 49, in case you’d like to check my facts. Check page 51, same book, and you’ll learn than "In Denmark… pork herds that have a high prevalence of Salmonella… are slaughtered separately from animals that come from herds with a low prevalence of Salmonella in order to avoid cross-contamination during slaughter and dressing; they are also used only in cooked products." to read a thoroughly researched discussion of the outbreak (with actual references!) focusing on what did consumers know, where did they get that information, and what did they do in response to the advisories issued by the FDA warning them not to eat fresh spinach,

to read a thoroughly researched discussion of the outbreak (with actual references!) focusing on what did consumers know, where did they get that information, and what did they do in response to the advisories issued by the FDA warning them not to eat fresh spinach,.jpg) raw milk cheese in France, and any call to ban such a fundamental part of French culture would meet with enormous resistance there." This is exactly why it doesn’t come down to science in the end. Science informs, but policy makers then deliberate, considering the science and other factors (including cultural preference), before making a decision.

raw milk cheese in France, and any call to ban such a fundamental part of French culture would meet with enormous resistance there." This is exactly why it doesn’t come down to science in the end. Science informs, but policy makers then deliberate, considering the science and other factors (including cultural preference), before making a decision. food catered by Hy-Vee here in Manhattan, KS. To my surprise, and delight, I observed the delivery chef test each one of the lasagna platters with a digital thermometer, and write down each temperature on a temp. sheet. Our club’s president then signed the sheet and we went about our business. Today, I called Hy-Vee to ask a few questions. Here’s the scoop.

food catered by Hy-Vee here in Manhattan, KS. To my surprise, and delight, I observed the delivery chef test each one of the lasagna platters with a digital thermometer, and write down each temperature on a temp. sheet. Our club’s president then signed the sheet and we went about our business. Today, I called Hy-Vee to ask a few questions. Here’s the scoop..jpg) batch. They fill in the temp. sheet, have it signed by the customer and leave printed instructions to discard any leftover food within 4 hours due to food safety risks past that timeframe. Now that I don’t have to worry about food poisoning from these events, I can focus on not contaminating my food with formalin.

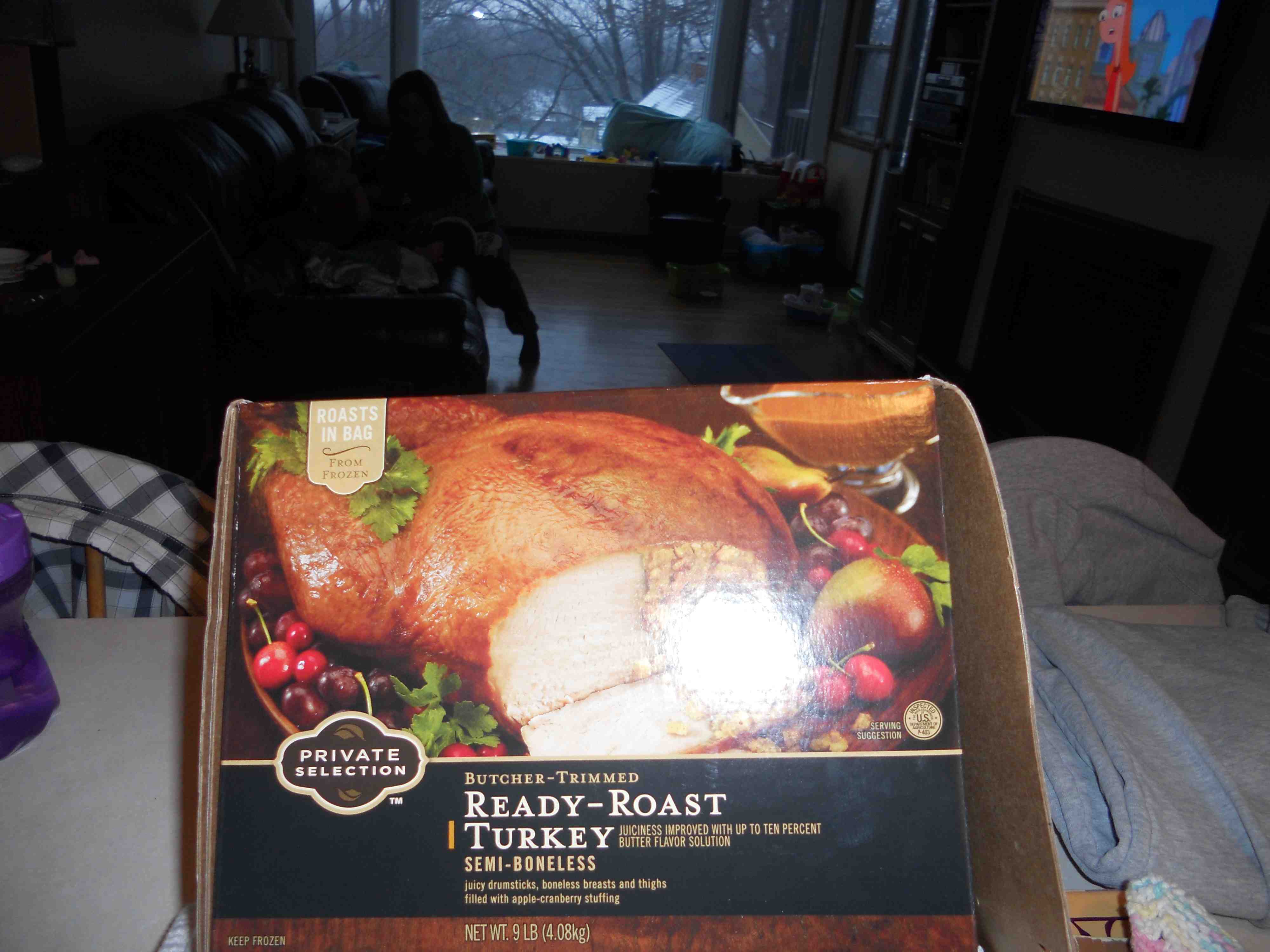

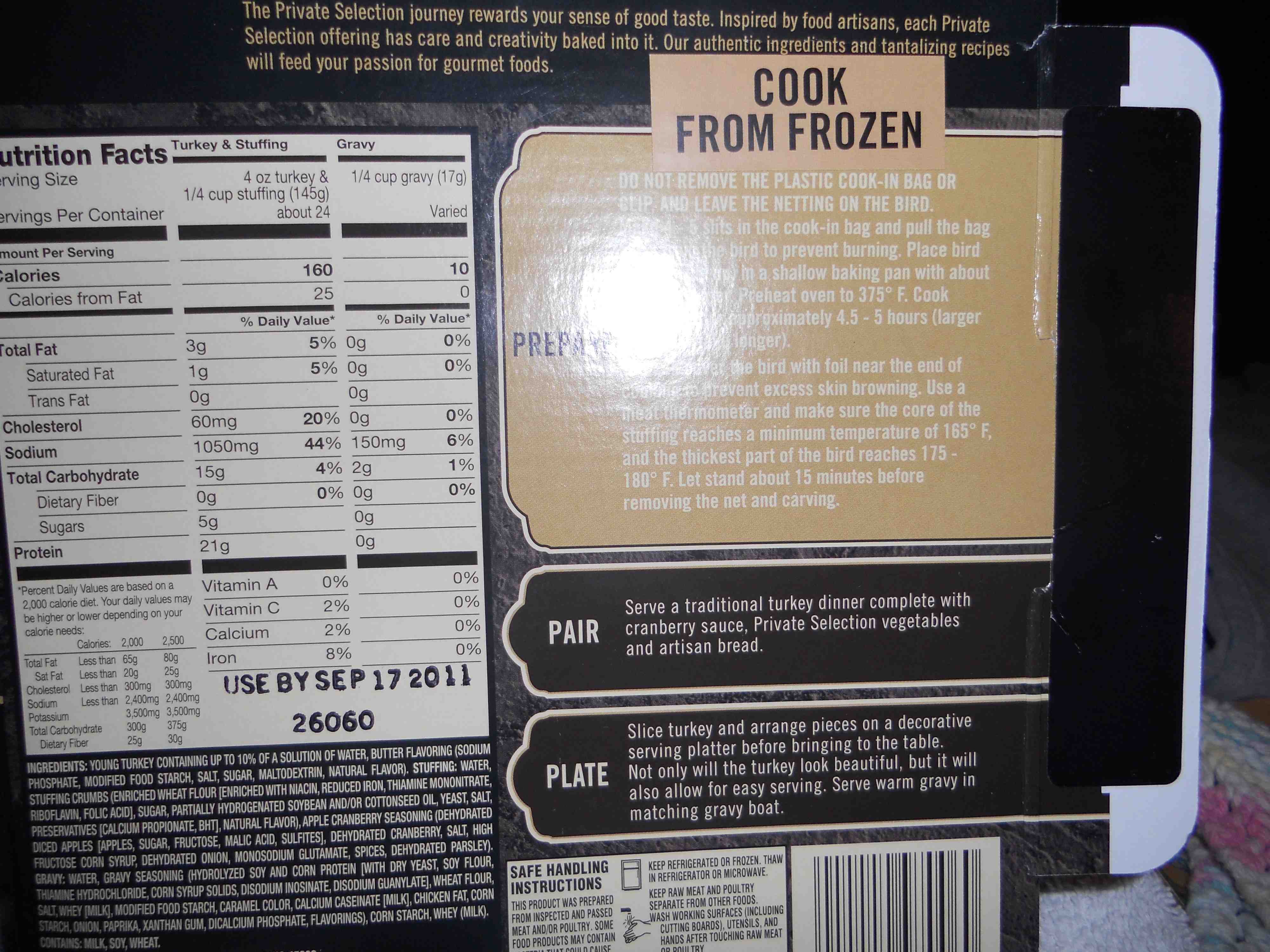

batch. They fill in the temp. sheet, have it signed by the customer and leave printed instructions to discard any leftover food within 4 hours due to food safety risks past that timeframe. Now that I don’t have to worry about food poisoning from these events, I can focus on not contaminating my food with formalin. character apparently farting), I took the opportunity to try out the frozen Kroger Private Selection Ready-Roast Turkey.

character apparently farting), I took the opportunity to try out the frozen Kroger Private Selection Ready-Roast Turkey. because of the stuffing, not just piping hot), slice and serve with homemade whole wheat rolls from scratch, drink more beer and wine and watch bad football. Converse (not the shoes).

because of the stuffing, not just piping hot), slice and serve with homemade whole wheat rolls from scratch, drink more beer and wine and watch bad football. Converse (not the shoes)..jpg) were linked to consuming poultry liver parfait or pâté.

were linked to consuming poultry liver parfait or pâté. .jpg) hot all the way through. The centre should reach a temperature of 70°C for two minutes or the equivalent time and temperature.

hot all the way through. The centre should reach a temperature of 70°C for two minutes or the equivalent time and temperature.