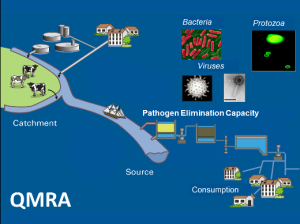

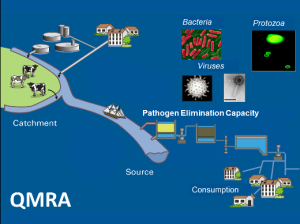

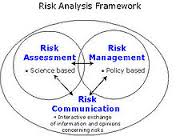

The current issue of Risk Analysis contains several papers regarding QMRA and Salmonella.

In a recent report from the World Health Organisation, the global impact of Salmonella in 2010 was estimated to be 65–382 million illnesses and 43,000–88,000 deaths, resulting in a disease burden of 3.2–7.2 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).[3] Controlling Salmonella in the food chain will require intervention measures, which come at a significant cost but these should be balanced with the cost of Salmonella infections to society.[5]

In a recent report from the World Health Organisation, the global impact of Salmonella in 2010 was estimated to be 65–382 million illnesses and 43,000–88,000 deaths, resulting in a disease burden of 3.2–7.2 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).[3] Controlling Salmonella in the food chain will require intervention measures, which come at a significant cost but these should be balanced with the cost of Salmonella infections to society.[5]

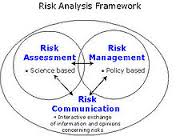

Despite a wealth of published research work relating to Salmonella, many countries still struggle with identifying the best ways to prevent and control foodborne salmonellosis. Two questions are particularly important to answer in this respect: ([1]) What are the most important sources of human salmonellosis within the country? and ([2]) When a (livestock) source is identified as important, how do we best prevent and control the dissemination of Salmonella through that farm-to-consumption pathway? The articles presented in this series continue the desire to answer these questions and hence eventually contribute to the reduction in the disease burden of salmonellosis in humans.

Risk Analysis, 36: 433–436

Snary, E. L., Swart, A. N. and Hald, T.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/risa.12605/abstract

Application of molecular typing results in source attribution models: the case of multiple locus variable number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA) of Salmonella isolates obtained from integrated surveillance in Denmark

Risk Analysis, 36: 571–588

de Knegt, L. V., Pires, S. M., Löfström, C., Sørensen, G., Pedersen, K., Torpdahl, M., Nielsen, E. M. and Hald, T.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/risa.12483/abstract

Salmonella is an important cause of bacterial foodborne infections in Denmark. To identify the main animal-food sources of human salmonellosis, risk managers have relied on a routine application of a microbial subtyping-based source attribution model since 1995. In 2013, multiple locus variable number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA) substituted phage typing as the subtyping method for surveillance of S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium isolated from animals, food, and humans in Denmark.

The purpose of this study was to develop a modeling approach applying a combination of serovars, MLVA types, and antibiotic resistance profiles for the Salmonella source attribution, and assess the utility of the results for the food safety decisionmakers. Full and simplified MLVA schemes from surveillance data were tested, and model fit and consistency of results were assessed using statistical measures. We conclude that loci schemes STTR5/STTR10/STTR3 for S. Typhimurium and SE9/SE5/SE2/SE1/SE3 for S. Enteritidis can be used in microbial subtyping-based source attribution models. Based on the results, we discuss that an adjustment of the discriminatory level of the subtyping method applied often will be required to fit the purpose of the study and the available data. The issues discussed are also considered highly relevant when applying, e.g., extended multi-locus sequence typing or next-generation sequencing techniques.

The purpose of this study was to develop a modeling approach applying a combination of serovars, MLVA types, and antibiotic resistance profiles for the Salmonella source attribution, and assess the utility of the results for the food safety decisionmakers. Full and simplified MLVA schemes from surveillance data were tested, and model fit and consistency of results were assessed using statistical measures. We conclude that loci schemes STTR5/STTR10/STTR3 for S. Typhimurium and SE9/SE5/SE2/SE1/SE3 for S. Enteritidis can be used in microbial subtyping-based source attribution models. Based on the results, we discuss that an adjustment of the discriminatory level of the subtyping method applied often will be required to fit the purpose of the study and the available data. The issues discussed are also considered highly relevant when applying, e.g., extended multi-locus sequence typing or next-generation sequencing techniques.

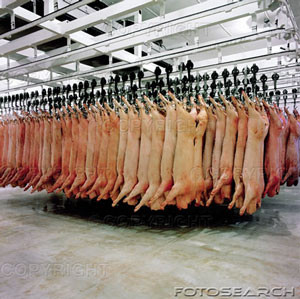

Assessing the effectiveness of on-farm and abattoir interventions in reducing pig meat–borne Salmonellosis within E.U. member states

Risk Analysis, 36: 546–56

Hill, A. A., Simons, R. L., Swart, A. N., Kelly, L., Hald, T. and Snary, E. L.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/risa.12568/abstract

As part of the evidence base for the development of national control plans for Salmonella spp. in pigs for E.U. Member States, a quantitative microbiological risk assessment was funded to support the scientific opinion required by the EC from the European Food Safety Authority. The main aim of the risk assessment was to assess the effectiveness of interventions implemented on-farm and at the abattoir in reducing human cases of pig meat–borne salmonellosis, and how the effects of these interventions may vary across E.U. Member States. Two case study Member States have been chosen to assess the effect of the interventions investigated. Reducing both breeding herd and slaughter pig prevalence were effective in achieving reductions in the number of expected human illnesses in both case study Member States. However, there is scarce evidence to suggest which specific on-farm interventions could achieve consistent reductions in either breeding herd or slaughter pig prevalence.

Hypothetical reductions in feed contamination rates were important in reducing slaughter pig prevalence for the case study Member State where prevalence of infection was already low, but not for the high-prevalence case study. The most significant reductions were achieved by a 1- or 2-log decrease of Salmonella contamination of the carcass post-evisceration; a 1-log decrease in average contamination produced a 90% reduction in human illness. The intervention analyses suggest that abattoir intervention may be the most effective way to reduce human exposure to Salmonella spp. However, a combined farm/abattoir approach would likely have cumulative benefits. On-farm intervention is probably most effective at the breeding-herd level for high-prevalence Member States; once infection in the breeding herd has been reduced to a low enough level, then feed and biosecurity measures would become increasingly more effective.

Hypothetical reductions in feed contamination rates were important in reducing slaughter pig prevalence for the case study Member State where prevalence of infection was already low, but not for the high-prevalence case study. The most significant reductions were achieved by a 1- or 2-log decrease of Salmonella contamination of the carcass post-evisceration; a 1-log decrease in average contamination produced a 90% reduction in human illness. The intervention analyses suggest that abattoir intervention may be the most effective way to reduce human exposure to Salmonella spp. However, a combined farm/abattoir approach would likely have cumulative benefits. On-farm intervention is probably most effective at the breeding-herd level for high-prevalence Member States; once infection in the breeding herd has been reduced to a low enough level, then feed and biosecurity measures would become increasingly more effective.

The Frozen Broccoli Cuts were distributed to stores in the following states: Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, Florida, Georgia, Alabama, South Carolina and North Carolina.

The Frozen Broccoli Cuts were distributed to stores in the following states: Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, Florida, Georgia, Alabama, South Carolina and North Carolina.