On June 10, 2016, U.S. Food and Drug Administration whole genome sequencing on E. coli O121 isolates recovered from an open sample of General Mills flour belonging to one of the consumers who was sickened was found to be closely genetically related the clinical isolates from human illnesses. The flour came from a lot that General Mills has recalled.

To date, 38 people infected with the outbreak strain of E. coli O121 have been reported from 20 states. Illnesses started on dates ranging from December 21, 2015 to May 3, 2016. Ten ill people have been hospitalized. In its investigation, CDC learned that some people who got sick had eaten or handled raw dough.

To date, 38 people infected with the outbreak strain of E. coli O121 have been reported from 20 states. Illnesses started on dates ranging from December 21, 2015 to May 3, 2016. Ten ill people have been hospitalized. In its investigation, CDC learned that some people who got sick had eaten or handled raw dough.

FDA’s traceback investigation determined that the raw dough eaten or handled by ill people or used in restaurant locations was made using General Mills flour that was produced in the same week in November 2015 at the General Mills facility in Kansas City, Missouri. Epidemiology and traceback evidence available at this time indicate that General Mills flour manufactured at this facility is the likely source of the outbreak.

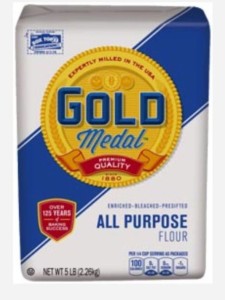

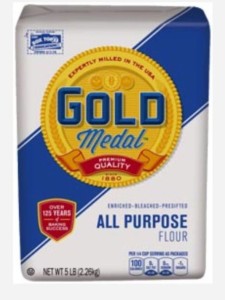

On May 31, 2016, following a conference call among FDA, CDC and the firm, General Mills conducted a voluntary recall of flour products produced between November 14, 2015 and December 4, 2015. Recalled products are sold in stores nationwide or may be in consumers’ pantries and are sold under three brand names: Gold Medal flour, Signature Kitchens flour and Gold Medal Wondra flour. The varieties include unbleached, all-purpose, and self-rising flours.

General Mills also sells bulk flour to customers who use it to make other products. General Mills has contacted these customers directly to inform them of the recall. FDA is working with General Mills to ensure that the customers have been notified, and to evaluate the recall for effectiveness.

Flour has a long shelf life, and bags of flour may be kept in peoples’ homes for a long time. Consumers unaware of the recall could continue to eat these recalled flours and potentially get sick. If consumers have any of these recalled flours in their homes, they should throw them away.

(this is bad)

People usually get sick from STEC O121 2-8 days (average of 3-4 days) after swallowing the bacteria. Most people develop diarrhea (often bloody) and abdominal cramps. Most people recover within a week.

People usually get sick from STEC O121 2-8 days (average of 3-4 days) after swallowing the bacteria. Most people develop diarrhea (often bloody) and abdominal cramps. Most people recover within a week.

Some illnesses last longer and can be more severe, resulting in a type of kidney failure called hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). HUS can occur in people of any age, but is most common in young children under 5 years, older adults, and people with weakened immune systems.

Restaurants and retailers should throw away any recalled General Mills flour. Some ill people reported handling raw dough at restaurants prior to eating their meal. Restaurants that allow their customers to handle raw dough should evaluate whether this practice is appropriate.

Restaurants and retailers should be aware that flour may be a source of pathogens and should control the potential for cross-contamination of food processing equipment and the food processing environment. They should follow the steps below:

Wash and sanitize display cases and refrigerators where potentially contaminated products were stored.

Wash and sanitize cutting boards, surfaces, and utensils used to prepare, serve, or store potentially contaminated products.

Wash hands with hot water and soap following the cleaning and sanitation process.

Retailers, restaurants, and other food service operators who have processed and packaged any potentially contaminated products need to be concerned about cross contamination of cutting surfaces and utensils through contact with the potentially contaminated products.

Regular frequent cleaning and sanitizing of food contact surfaces and utensils used in food preparation may help to minimize the likelihood of cross-contamination.

(this is bad)

What Do Consumers Need To Do?

What Do Consumers Need To Do?

The recalled General Mills products have a long shelf-life, and they may be in peoples’ homes. Consumers unaware of the recall could continue to eat these products and potentially get sick.

If consumers have these products in their homes, they should throw it away. As a precaution, flour no longer stored in its original packaging should be discarded if it could be covered by this recall, and the containers used to store this flour should be thoroughly washed and sanitized.

Three people who became ill reported handling raw dough at restaurants prior to eating their meal. As a precaution, consumers, especially children, should not handle raw dough at home or at restaurant locations.

FDA warns against eating raw dough products made with any brand of flour or baking mix before cooking. Consumers should always practice safe food handling and preparation measures when handling flour. The FDA recommends following these safe food-handling practices to stay healthy:

Do not eat or play with any raw cookie dough or any other raw dough product made with flour that is intended to be cooked or baked.

Follow package directions on baking mixes and other flour-containing products for proper cooking temperatures and for specified times.

Wash hands, work surfaces, and utensils thoroughly after contact with raw dough products containing flour.

Keep raw foods separate from other foods while preparing them to prevent any contamination that might be present from spreading.

Eight cases of the E. coli O26 infection have been identified in children who attend the nursery.

Eight cases of the E. coli O26 infection have been identified in children who attend the nursery.