On Christmas Eve, 2009, the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced some 248,000 pounds of tenderized beef were being recalled and was eventually linked to 21 E. coli O157:H7 infections in 16 states.

In Sept. 2012, at least four people in Canada were sickened by E. coli O157:H7 in needle or blade tenderized meat linked to the XL outbreak and sold at Costco.

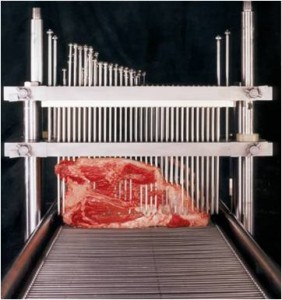

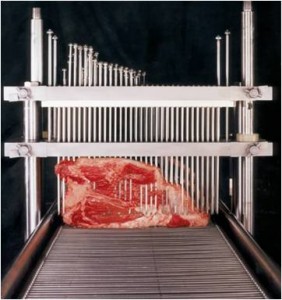

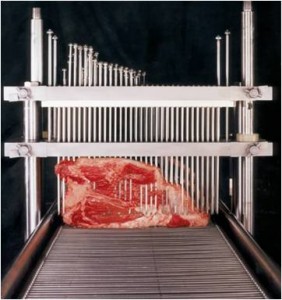

Needle or blade tenderized beef is typically used on tougher cuts of beef or pork to break down muscle fibers or to inject marinade into meat. About 50 million pounds of needle- or  blade-tenderized meat is produced in the U.S. each month, according to a federal study, but it’s not required to be labeled.

blade-tenderized meat is produced in the U.S. each month, according to a federal study, but it’s not required to be labeled.

All hamburger should be cooked to a thermometer-verified 160F because it’s all ground up – the outside, which can be laden with poop, is on the inside. With steaks, the thought has been that searing on the outside will take care of any poop bugs like E. coli and the inside is (sorta?) clean. But what if needles pushed the E. coli on the outside of the steak to the inside?

Luchansky et al. wrote in the July 2009 Journal of Food Protection that based on inoculation studies, cooking on a commercial gas grill is effective at eliminating relatively low levels of the pathogen that may be distributed throughout a blade-tenderized steak. But others recommend such meat be labeled because it may require a higher cooking temperature.

In Aug. 2012, U.S. consumer groups wrote to U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack urging him to immediately approve a proposal to label mechanically tenderized beef products. Without labeling to identify these products as mechanically tenderized and non-intact products, and information on how to properly cook these products, consumers may be unknowingly at risk for foodborne illness. Labeling of mechanically tenderized products would allow consumers to identify these products in the supermarket.

As early as 1999, USDA/FSIS publicly stated that mechanically tenderized meat products were considered non-intact products because the product had been pierced and surface pathogens could have been translocated to the interior of the product.

USDA/FSIS further stated, “As a result, customary cooking of these products may not be adequate to kill the pathogens.” At that time, USDA/FSIS said that they would not require a label for these products but strongly encouraged industry to label all non-intact, mechanically tenderized meat products with safe food handling guidance. To date, industry labeling of these products is rare.

In June 2010, the Conference for Food Protection petitioned FSIS to put forward regulations that would require mechanically tenderized products to be labeled.

Now, with glacial haste, Health Canada has started a review of the science around the safe handling and cooking of beef products that are mechanically tenderized, to identify what advice should be communicated to consumers and the food industry.

Some meat handlers and even some Canadians at home tenderize cuts of beef, including steaks and roasts, using machines or tools made for this process.

While this review is ongoing, and to make sure that any bacteria that may be present in the meat are killed, Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada are encouraging Canadians to cook mechanically tenderized steak and beef cuts to an internal temperature of at least 71 degrees Celsius (160 degrees Fahrenheit).

Why buy expensive steak if it has to be cooked to 160F? Buy cheap hamburger.

And how would consumers know what’s a needle tenderized cut of meat? There’s no labeling.

Health Canada is also actively working with the retail and food industry to support its efforts to identify mechanically tenderized beef for consumers through labels, signage or other means. The industry expects to start putting these measures in place over the next two to three weeks. In the meantime, should consumers be uncertain if a product has been mechanically tenderized, they are encouraged to ask the food seller or food service provider.

Matthew, a child “full of life, very intelligent despite his disability ” according to his mother, Angélique Gervraud, died February 22, 2019 at the Children’s Hospital of Bordeaux. He had been sick for more than a month after eating an undercooked burger at the beginning of January 2019 says his mom in a forum posted on his Facebook page.

Matthew, a child “full of life, very intelligent despite his disability ” according to his mother, Angélique Gervraud, died February 22, 2019 at the Children’s Hospital of Bordeaux. He had been sick for more than a month after eating an undercooked burger at the beginning of January 2019 says his mom in a forum posted on his Facebook page.