Alzheimer’s has affected me, indirectly, in ways I still can’t understand, but am trying.

My grandfather died of Alzheimer’s in the 1980s, when I was a 20-something.

My grandfather died of Alzheimer’s in the 1980s, when I was a 20-something.

It wasn’t pretty, so stark that my grandmother took her own life rather than spend winter days going to a hospital where the man she had been with for all those years increasingly didn’t recognize her.

Glen Campbell’s death yesterday from Alzheimer’s, and Gene Wilder’s before that, rekindled lots of conflicting emotions.

In 1995, I was a cocky PhD student and about to be a father for the fourth time, when I was summoned to a meeting with, Ken Murray.

I rode my bike to a local golf club, met the former long-time president of Schneiders Meats, and established a lifelong friendship.

When Ken told me about a project he had established at the University of Waterloo in 1993, the Murray Alzheimer Research and Education Program (MAREP), after his wife’s demise from the disease, I said, I can’t understand the hell of being the primary caregiver for so long, but I know of the side-effects.

Ken had heard I might know something of science-and-society stuff, and he actually funded my faculty position at the University of Guelph for the first two years.

Sure, other weasels at Guelph tried to appropriate the money, but Ken would have none of it.

For over 20 years now, I’ve tried to promote Ken’s vision, of making the best technology available to enhance the safety of the food supply.

I’ve got lots of demons, and what I’ve learned is that it’s best to be public about them. It removes the stigma. It makes one recognize they are not alone. It’s humbling (and that is good).

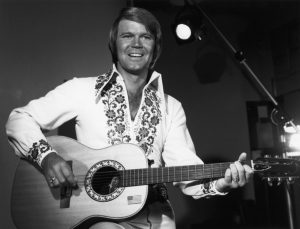

In addition to being an unbelievably gifted songwriter, session player, and hit maker, Glen Campbell was – directly or not – an outstanding advocate of awareness about Alzheimer’s.

In addition to being an unbelievably gifted songwriter, session player, and hit maker, Glen Campbell was – directly or not – an outstanding advocate of awareness about Alzheimer’s.

Michael Pollack writes in The New York Times obituary that Glen Campbell, the sweet-voiced, guitar-picking son of a sharecropper who became a recording, television and movie star in the 1960s and ’70s, waged a publicized battle with alcohol and drugs and gave his last performances while in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, died on Tuesday in Nashville. He was 81.

Tim Plumley, his publicist, said the cause was Alzheimer’s.

Mr. Campbell revealed that he had the disease in June 2011, saying it had been diagnosed six months earlier. He also announced that he was going ahead with a farewell tour later that year in support of his new album, “Ghost on the Canvas.” He and his wife, Kimberly Campbell, told People magazine that they wanted his fans to be aware of his condition if he appeared disoriented onstage.

What was envisioned as a five-week tour turned into 151 shows over 15 months. Mr. Campbell’s last performance was in Napa, Calif., on Nov. 30, 2012, and by the spring of 2014 he had moved into a long-term care and treatment center near Nashville.

Mr. Campbell released his final studio album, “Adiós,” in June. The album, which included guest appearances by Willie Nelson, Vince Gill and three of Mr. Campbell’s children, was recorded after his farewell tour.

That tour and the way he and his family dealt with the sometimes painful progress of his disease were chronicled in a 2014 documentary, “Glen Campbell: I’ll Be Me,” directed by the actor James Keach. Former President Bill Clinton, a fellow Arkansas native, appears in the film and praises Mr. Campbell for having the courage to become a public face of Alzheimer’s.

At the height of his career, Mr. Campbell was one of the biggest names in show business, his appeal based not just on his music but also on his easygoing manner and his apple-cheeked, all-American good looks. From 1969 to 1972 he had his own weekly television show, “The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour.” He sold an estimated 45 million records and had numerous hits on both the pop and country charts. He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2005.

Decades after Mr. Campbell recorded his biggest hits — including “Wichita Lineman,” “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” and “Galveston” (all written by Jimmy Webb, his frequent collaborator for nearly 40 years) and “Southern Nights” (1977), written by Allen Toussaint, which went to No. 1 on pop as well as country charts — a resurgence of interest in older country stars brought him back onto radio stations.

Like Bobbie Gentry, with whom he recorded two Top 40 duets, and his friend Roger Miller, Mr. Campbell was a hybrid stylist, a crossover artist at home in both country and pop music.

Although he never learned to read music, Mr. Campbell was at ease not just on guitar but also on banjo, mandolin and bass. He wrote in his autobiography, “Rhinestone Cowboy” (1994) — the title was taken from one of his biggest hits — that in 1963 alone his playing and singing were heard on 586 recorded songs.

He could be a cut-up in recording sessions. “With his humor and energetic talents, he kept many a record date in stitches as well as fun to do,” the electric bassist Carol Kaye, who often played alongside Mr. Campbell, said in an interview in 2011. “Even on some of the most boring, he’d stand up and sing some off-color country song — we’d almost have a baby trying not to bust a gut laughing.”

He could be a cut-up in recording sessions. “With his humor and energetic talents, he kept many a record date in stitches as well as fun to do,” the electric bassist Carol Kaye, who often played alongside Mr. Campbell, said in an interview in 2011. “Even on some of the most boring, he’d stand up and sing some off-color country song — we’d almost have a baby trying not to bust a gut laughing.”

After playing on many Beach Boys sessions, Mr. Campbell became a touring member of the band in late 1964, when its leader, Brian Wilson, decided to leave the road to concentrate on writing and recording. He remained a Beach Boy into the first few months of 1965.

Mr. Campbell had his most famous movie role in 1969, in the original version of “True Grit.” He had the non-singing part of a Texas Ranger who joins forces with John Wayne and Kim Darby to hunt down the killer of Ms. Darby’s father. (Matt Damon had the role in a 2010 remake.) The next year, Mr. Campbell and the New York Jets quarterback Joe Namath played ex-Marines in “Norwood,” based on a novel by Charles Portis, the author of “True Grit.”

Mr. Campbell made his Las Vegas debut in 1970 and, a year later, performed at the White House for President Richard M. Nixon and for Queen Elizabeth II in London.

But his life in those years had a dark side. “Frankly, it is very hard to remember things from the 1970s,” he wrote in his autobiography. Though his recording and touring career was booming, he began drinking heavily and later started using cocaine. He would annoy his friends by quoting from the Bible while high. “The public had no idea how I was living,” he recalled.

In 1980, after his third divorce, he said: “Perhaps I’ve found the secret for an unhappy private life. Every three years I go and marry a girl who doesn’t love me, and then she proceeds to take all my money.” That year, he had a short, tempestuous and very public affair with the singer Tanya Tucker, who was about half his age.

He credited his fourth wife, the former Kimberly Woollen, with keeping him alive and straightening him out — although he would continue to have occasional relapses for many years. He was arrested in November 2003 in Phoenix and charged with extreme drunken driving and leaving the scene of an accident. He pleaded guilty and served 10 nights in jail in 2004.

I cried with many emotions when I first watched his documentary, I’ll Be Me.

And I’ll watch it again today with humility, respect and gratitude, to people like Glen and Ken.

.jpg) conducted to provide improved and updated estimates of the cost of foodborne illness by adding a replication of the 2011 CDC model to existing cost-of-illness models. The basic cost-of-illness model includes economic estimates for medical costs, productivity losses, and illness-related mortality (based on hedonic value-of-statistical-life studies).

conducted to provide improved and updated estimates of the cost of foodborne illness by adding a replication of the 2011 CDC model to existing cost-of-illness models. The basic cost-of-illness model includes economic estimates for medical costs, productivity losses, and illness-related mortality (based on hedonic value-of-statistical-life studies).