Every time some government type says there are more cases of E. coli O157:H7 and other dangerous bacteria in the summertime because people barbeque more, I cringe. It’s one of those blame-the-consumer comments when the reality is more complicated.

.jpg) Most food safety interventions are designed to reduce or eliminate pathogen loads – to lower the number of harmful bugs from farm-to-fork. A piece of highly-contaminated meat can wreck cross-contamination havoc in a food service or home kitchen.

Most food safety interventions are designed to reduce or eliminate pathogen loads – to lower the number of harmful bugs from farm-to-fork. A piece of highly-contaminated meat can wreck cross-contamination havoc in a food service or home kitchen.

Elizabeth Weise writes in USA Today today that animals carry higher levels of E. coli O157:H7 and friends during the summer months, and summarizes efforts to lower bacterial loads on animals entering slaughter plants.

Jerold Mande, USDA deputy undersecretary for food safety, said last month,

"To take the next big step forward on food safety, we need to do more to have fewer pathogens on food animals when they arrive at the slaughterhouse gate.”

Jim Marsden of Kansas State University said that microbiologically, the biggest "bang for the buck" is cleaning the bacteria off the hide or the carcass to keep it from coming into contact with the meat.

Weise writes that a number of possible interventions are in the works. Each, it is hoped, might take down the incidence of E. coli O157:H7 by a factor of 100. Below is the edited list.

Vaccines: Gut warfare

Probably the most hopeful are vaccines that lower the amount of O157:H7 in cattle’s guts. Two are furthest along, one from a Minnesota company called Epitopix and one by a Canadian company called Bioniche Life Sciences. Epitopix’s vaccine has received preliminary approval from the USDA and is being tested in the USA. Bioniche’s vaccine was approved in Canada last year and is in the approval process in the USA. In addition, scientists at the USDA’s National Animal Disease Center in Ames, Iowa, have developed two more vaccines.

Field trials of the Epitopix vaccine showed that 86% of vaccinated cattle stopped shedding O157:H7 bacteria in their feces. Of those that still were shedding bacteria, there was a 98% reduction in the amount, says Daniel Thomson (left, photo from USA Today), a veterinarian and professor of Production Medicine at Kansas State University in Manhattan, Kan., who has studied the effectiveness of vaccine for the company.

Field trials of the Epitopix vaccine showed that 86% of vaccinated cattle stopped shedding O157:H7 bacteria in their feces. Of those that still were shedding bacteria, there was a 98% reduction in the amount, says Daniel Thomson (left, photo from USA Today), a veterinarian and professor of Production Medicine at Kansas State University in Manhattan, Kan., who has studied the effectiveness of vaccine for the company.

The issue for cattlemen will be the costs of the two or three shots necessary to create immunity and the wear and tear on the cattle caused by bringing them in to be vaccinated. Going through the chute that holds them still while they’re given the shot, necessary to safeguard workers, can cause some cattle to become agitated.

Phages: A spray of bacteria fighters

Cattle walking through a car-wash-like spray of bacteria-eating viruses called phages sounds more science fiction than feedlot, but it’s actually in use across the USA. In cattle, a phage that is specific to E. coli O157:H7 is sprayed on the animals one to four hours before they’re slaughtered. "They like to have them soak," says Dan Schaefer, director of beef research and development at in Wichita. Cargill is testing the spray at one of its plants.

Probiotics: ‘Exclusion’ cultures

Basically these are bacterial cultures much like those in yogurt, given to cattle in their feed. They’re called "competitive exclusion" cultures because they out-compete the bad bacteria and exclude them in the animals’ guts. Michael Doyle, director of the Center for Food Safety at the University of Georgia in Griffin, spent years investigating them.

One for E. coli O157:H7 "worked really well for a while and then it stopped working for a while," he says. Doses required are often higher than those claimed by the companies that sell them, he says. Currently these aren’t approved by USDA or FDA as E. coli reduction methods, so the companies that market them can’t make any specific claims for them.

Sodium chlorate: A ‘suicide pill’

This chemical is used in part to do environmentally safe paper bleaching. But administered in extremely small amounts, it also plays a deadly trick on E. coli O157:H7 and salmonella.

In the oxygen-free environment of a cow’s gut, these bacteria are able to obtain energy from nitrogen. But they can’t tell the difference between nitrogen and chlorate, so if there’s chlorate present, they try to use that. This turns the chlorate into bleach, killing the bacteria from the inside without harming the animal.

Grain vs. high-quality hay

Research in Texas, Kansas and Idaho has shown that switching cattle from grain to a more expensive diet of high quality hay before slaughter may lower E. coli O157:H7 rates, though the findings have not always been consistent.

From an epidemiologic standpoint, it’s clear that these pre-slaughter interventions lower the E. coli O157:H7 burden in the cattle, says Guy Loneragan, a professor of animal science and expert in O157:H7 in cattle at West Texas A&M University in Canyon, Texas.

The question is whether investing money on the ranch and feedlot will save money at the packing plant.

After public health and animal welfare experts inspected them, council officials ordered them to be shot dead.

After public health and animal welfare experts inspected them, council officials ordered them to be shot dead.

with the consultation process ahead of their publication.

with the consultation process ahead of their publication.

commercial. Such was the power of Oprah.

commercial. Such was the power of Oprah. expediting regulations prohibiting ruminant protein in ruminant feeds, boosting

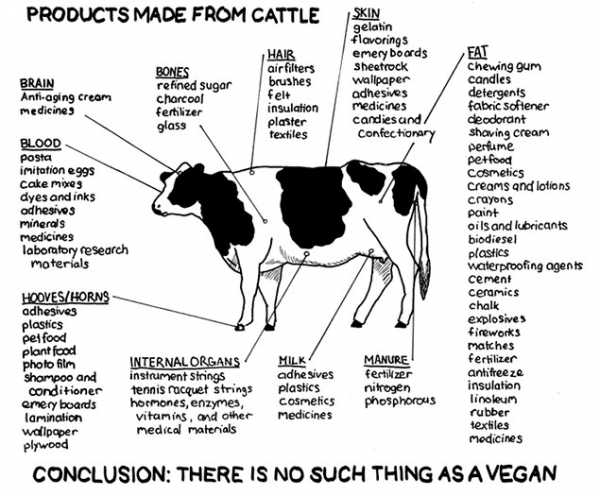

expediting regulations prohibiting ruminant protein in ruminant feeds, boosting longer stand) were rendered and fed to other cattle, and that BSE could make AIDS look like a common cold. The chief scientist for the U.S. National Cattleman’s Beef Association, rather than stressing the risk management actions that had been taken, was left arguing that cows were not vegetarians because they drank milk.

longer stand) were rendered and fed to other cattle, and that BSE could make AIDS look like a common cold. The chief scientist for the U.S. National Cattleman’s Beef Association, rather than stressing the risk management actions that had been taken, was left arguing that cows were not vegetarians because they drank milk. immediately washed, the skin is removed, and within minutes, the workers also remove the hooves, the hide and the head. The carcass is then moved to a giant cooler, where it stays for up to two days. After it’s been inspected and graded, it’s packaged, loaded on trucks and soon ends up in our local restaurants and stores.

immediately washed, the skin is removed, and within minutes, the workers also remove the hooves, the hide and the head. The carcass is then moved to a giant cooler, where it stays for up to two days. After it’s been inspected and graded, it’s packaged, loaded on trucks and soon ends up in our local restaurants and stores. committed to doing it right. And I believe that when animals are handled with dignity and harvested carefully, that’s the natural order of things,’ says Nicole.

committed to doing it right. And I believe that when animals are handled with dignity and harvested carefully, that’s the natural order of things,’ says Nicole.

Gert Hahne, a ministry spokesman in Hannover, said

Gert Hahne, a ministry spokesman in Hannover, said government succeeded by not only saying the right things, but by removing potentially contaminated product from commerce in a timely manner. Actions and words must be consistent to manage any crisis and garner public support.”

government succeeded by not only saying the right things, but by removing potentially contaminated product from commerce in a timely manner. Actions and words must be consistent to manage any crisis and garner public support.” food supply. All you had to do, according to Karen Selick, was grow up on a farm, hunt, join the Armed Forces and get a degree in biomedical toxicology.

food supply. All you had to do, according to Karen Selick, was grow up on a farm, hunt, join the Armed Forces and get a degree in biomedical toxicology.  adjectives. It comes free-range, cage-free, antibiotic-free, raised on vegetarian feed, organic, even air-chilled.

adjectives. It comes free-range, cage-free, antibiotic-free, raised on vegetarian feed, organic, even air-chilled. With the slaughter system, David Pitman, whose family owns Mary’s Chickens, said,

With the slaughter system, David Pitman, whose family owns Mary’s Chickens, said,.jpg) name by Horace McCoy. It focuses on a disparate group of characters desperate to win a Depression-era dance marathon and the opportunistic emcee who urges them on to victory.

name by Horace McCoy. It focuses on a disparate group of characters desperate to win a Depression-era dance marathon and the opportunistic emcee who urges them on to victory..jpg)

Apparently, Tijssen’s house had been under surveillance for several days last November before officers from the Ministry of Natural Resources and Ottawa police stopped a car leaving the property and confiscated 18 kilograms of pork. Tijssen and a friend had jointly bought a pig and slaughtered it.

Apparently, Tijssen’s house had been under surveillance for several days last November before officers from the Ministry of Natural Resources and Ottawa police stopped a car leaving the property and confiscated 18 kilograms of pork. Tijssen and a friend had jointly bought a pig and slaughtered it. Brent Ross, a spokesman for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, said the ministry moderates its enforcement of meat handling rules for religious or ethnic reasons, for example, when Muslims slaughter animals for religious reasons.

Brent Ross, a spokesman for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, said the ministry moderates its enforcement of meat handling rules for religious or ethnic reasons, for example, when Muslims slaughter animals for religious reasons..jpg) Most food safety interventions are designed to reduce or eliminate pathogen loads – to lower the number of harmful bugs from farm-to-fork. A piece of highly-contaminated meat can wreck cross-contamination havoc in a food service or home kitchen.

Most food safety interventions are designed to reduce or eliminate pathogen loads – to lower the number of harmful bugs from farm-to-fork. A piece of highly-contaminated meat can wreck cross-contamination havoc in a food service or home kitchen.  Field trials of the Epitopix vaccine showed that 86% of vaccinated cattle stopped shedding O157:H7 bacteria in their feces. Of those that still were shedding bacteria, there was a 98% reduction in the amount, says Daniel Thomson (left, photo from USA Today), a veterinarian and professor of Production Medicine at Kansas State University in Manhattan, Kan., who has studied the effectiveness of vaccine for the company.

Field trials of the Epitopix vaccine showed that 86% of vaccinated cattle stopped shedding O157:H7 bacteria in their feces. Of those that still were shedding bacteria, there was a 98% reduction in the amount, says Daniel Thomson (left, photo from USA Today), a veterinarian and professor of Production Medicine at Kansas State University in Manhattan, Kan., who has studied the effectiveness of vaccine for the company.