I’ve got a new gig.

I’m the head of food safety for the school tuck shop that is run by volunteers at daughter Sorenne’s school.

I’m the head of food safety for the school tuck shop that is run by volunteers at daughter Sorenne’s school.

The pay is lousy (non-existent) but the discussions are gold, and gets me back into what my friend Tanya deemed reality research – and that’s what my group has always been good at, going out and talking with people.

More practice than preaching.

The tuck shop serves meals for about 200 students, one day a week. It’s run by volunteers, and all profits go to the school.

It used to be run by a school employee, and the meals were purchased and then resold, at a loss. When that person moved on, some parents decided, we can do better that that.

Sorenne said she wanted relief from the drudgery of everyday school lunches, and I said, not until I check it out.

I put my hand up, and now am in charge of food safety.

Things happen that way.

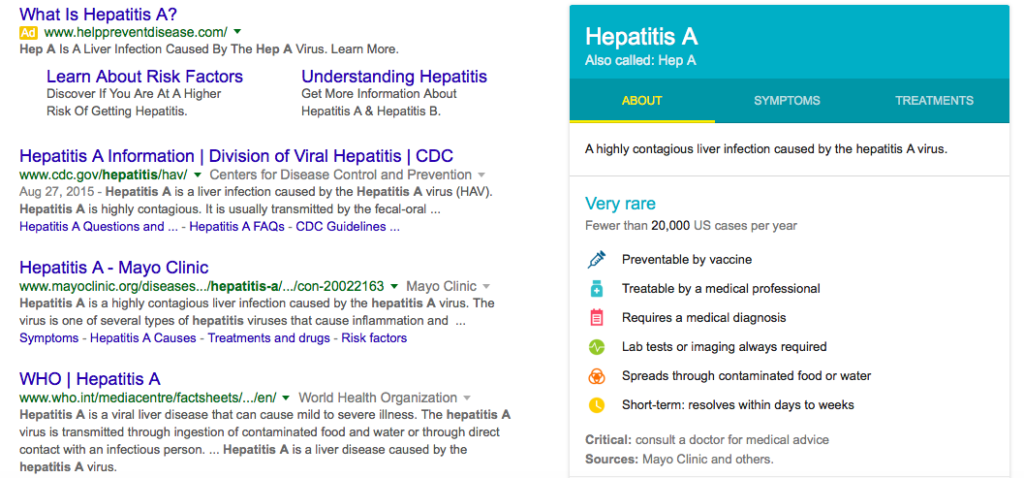

But there were no state resources for volunteers running a tuck shop.

We’ve been making it up as we go.

The questions at my kid’s school can be expanded to the larger community, especially with holiday potlucks.

I avoid the food at potlucks, church dinners and other community meals. I relish the social interaction, but I have no idea of the hand sanitation, the cooking methods, and other food safety factors that can make people barf and sometimes kill them.

I avoid the food at potlucks, church dinners and other community meals. I relish the social interaction, but I have no idea of the hand sanitation, the cooking methods, and other food safety factors that can make people barf and sometimes kill them.

Typically, health types will insist on some level of competency for people providing food, and they will get overruled by politicians who say things like, it’s common sense, and, we’ve always done things this way and never made anyone sick.

No one inspects the tuck shop I volunteer at.

But volunteers aren’t magically immune from making people sick.

The outbreaks are happening weekly at this point, tragically resulting in the death of an elderly woman in New Brunswick, Canada.

Over 15 years ago Rob Tauxe described the traditional foodborne illness outbreak as a scenario that ‘often follows a church supper, family picnic, wedding reception, or other social event.’

This scenario involves an acute and highly local outbreak, with a high inoculum dose and a high attack rate. The outbreak is typically immediately apparent to those in the local group, who promptly involve medical and public health authorities. The investigation identifies a food-handling error in a small kitchen that occurs shortly before consumption. The solution is also local.

Community gatherings around food awaken nostalgic feelings of the rural past — times when an entire town would get together on a regular basis, eat, enjoy company, and work together.

Public health regulations for community-based meals are inconsistent at best, and these events may or may not fall under inspection regulations. Additionally, in areas where community-based meals are inspected by public health there is pressure from the community to deregulate these events due to their volunteer nature.

Food handlers at CMEs are usually volunteers preparing food outside of their own home, often in a communal kitchen. They may not be accustomed to preparing food for a large group, the time constraints associated with food service, or even the tools, foods and processes used for the meal. These informal event infrastructures, as well as volunteer food handlers with no formal food safety training and a lack of commercial food preparation skills, provide a climate for potential food safety problems.

Foods prepared at home and then brought to CMEs also pose a hazard, as research has shown that poor food handling practices in the home often contribute to foodborne illness.

The tuck shop at Sorenne’s school has been running for six months, and we’re now on summer break, did a deep clean, and planning how best to go forward, in a way we can recruit future volunteers.

We also just ended the (ice) hockey season this past weekend and Sorenne told her teacher she wants to be a professional hockey player when she gets older.

There’s no money in that, or food safety, but it’s great to be part of a community.

I needed 40 hours of training to coach a rep girls hockey team in Canada, and 16 hours to coach in Australia.

I don’t need nothing to make people sick.

Dr. Douglas Powell is a former professor of food safety who shops, cooks and ferments from his home in Brisbane, Australia.

DISCLAIMER: The views and opinions expressed in this blog are those of the original creator and do not necessarily represent that of the Texas A&M Center for Food Safety or Texas A&M University.

Once the perfect human pathogen is in a restaurant, grocery store, or cruise ship – or school – it’s tough to get it out without some illnesses.

Once the perfect human pathogen is in a restaurant, grocery store, or cruise ship – or school – it’s tough to get it out without some illnesses.