Kathleen Glass started working at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Food Research Institute 30 years ago, studying various microbes — primarily those turning up in the meat and dairy industries — and assisting with food safety investigations.

She added her first fruit case last year with a Listeria monocytogenes outbreak in caramel apples.

She added her first fruit case last year with a Listeria monocytogenes outbreak in caramel apples.

Now, Glass and other researchers are working to better understand the needs of the tree fruit industry in order to help growers, packers and retailers meet new food safety regulations and ensure the safety of their products.

“The meat and dairy industries had problems 20 years ago. That’s really when we found our religion when it comes to food safety,” Glass said.

Fruit growers didn’t have as much to worry

A couple of consecutive outbreaks with ready-to-eat meat products led to significant changes in cleaning and sanitation in that industry, Glass said, as well as the addition of growth inhibitors to meat products so that Listeria can’t grow during the normal shelf life.

The changes sparked a 42 percent decrease in cases from 1996 to 2012.

The World Health Organization estimates an infectious dose of Listeria at about 10,000 cells or more.

“Just a couple of Listeria in our food products probably is not going to make us sick. That means we need to focus on foods that support growth — perishable things you should refrigerate, those with the right amount of moisture and the right acidity level,” Glass told growers and packers at December’s Washington State Tree Fruit Association Annual Meeting in Yakima, Washington.

Investigators eventually tied the Jan. 6, 2015, Listeria outbreak to a specific supplier of Granny Smith and Gala apples in California, marking the first direct tie of fresh whole apples to a serious food safety outbreak.

But there were some novel things about the case, Glass said. Healthy children were getting sick from an unusual food source: caramel apples.

But there were some novel things about the case, Glass said. Healthy children were getting sick from an unusual food source: caramel apples.

The apples were sanitized, dipped in hot caramel, and the pH of the apples was too low for minimum growth of the pathogen, which raised several questions.

Is this the work of a superbug? Are conditions present to allow growth? Could damage to the apple contribute?

Preliminary studies suggest that damage to apples could encourage microbial growth, Glass said. In this case, puncturing the apple with a stick allowed Listeria to translocate to the core.

In addition, deep depressions in apples may protect Listeria from hot caramel. Storage temperature also is an issue, with the apples stored at room temperature at retail, enabling Listeria growth.

Glass said it’s clear the industry is stepping up its efforts in the food safety arena and in environmental testing, which is the best way to determine if there’s an area of concern.

The problem is knowing if disinfectants are as effective as hoped.

“We have to try things that have been done elsewhere and apply things in different ways,” she said. “It’s a tough, tough thing, because they don’t have a great kill step. We don’t have any magic at this point, and more research is needed.”

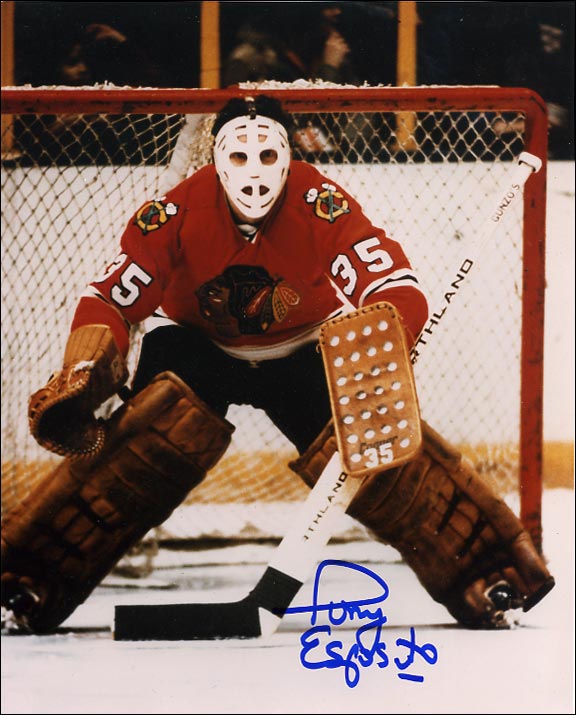

hockey for a bit, and home to the greatest NHL goaltender ever and my teenage-idol,

hockey for a bit, and home to the greatest NHL goaltender ever and my teenage-idol,

OK,

OK,.png)