We’re going to a birthday party Saturday a.m. at the park across the street from us.

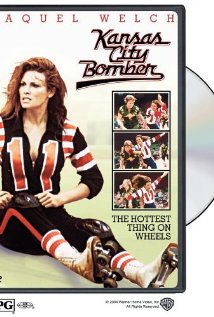

I got to know the mom by hanging out at Sorenne’s school – in a drop-off-and-pick-up way, not a creepy way – and at some point heard she was into roller derby, with her two daughters.

With my 5 daughters in (ice) hockey, I sparked up a conversation.

With my 5 daughters in (ice) hockey, I sparked up a conversation.

Seems that Unforgiving Bunny – that’s her roller derby handle – is a lawyer by day, and avid roller woman by night.

I thought of Unforgiving Bunny when I read the health authority of the district Mainz-Bingen is currently investigating several diseases of humans with the exciter of the hare plague (tulareämie).

And that’s our other roller derby friend, Abby of Manhattan, Kansas, (left) who got into the game once she moved to France (she was a student of Amy’s and great with little, bald Sorenne. Girl power.)

Hare plague can be transmitted from the animal to humans. A human-to-human transplant is nearly impossible and not known. Tularemia is highly treatable, but can take more severe curves in the individual case.

A common feature of the six affected that they had participated in early October on a vintage in the northern district. A few days later they got high fever and complained of a severe general feeling of illness. Three people had to be treated in the hospital. All have now been released as well again.

The case is unusual because infection with the pathogen in Germany are very rare and heaped even more rarely occur. Man is infected by direct contact with diseased animals, their organs or excretions. The pathogen can also be transferred through contaminated food.

The Health Authority is assisted in the search for causes of Landesuntersuchungsamt (LUA). It is investigated how the villagers could have come into contact with the pathogen. In parallel, the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) examines samples from the vineyard. The focus is on food, rabbits, rabbits and other environmental samples. The bacterium Francisella tularensis triggers a tularemia disease. It usually begins with an ulcer at the entrance of the pathogen, followed by flu-like symptoms such as fever, lymph node swelling, chills, malaise as well as headache and limb pain. The disease can be treated with antibiotics.

The Health Authority is assisted in the search for causes of Landesuntersuchungsamt (LUA). It is investigated how the villagers could have come into contact with the pathogen. In parallel, the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) examines samples from the vineyard. The focus is on food, rabbits, rabbits and other environmental samples. The bacterium Francisella tularensis triggers a tularemia disease. It usually begins with an ulcer at the entrance of the pathogen, followed by flu-like symptoms such as fever, lymph node swelling, chills, malaise as well as headache and limb pain. The disease can be treated with antibiotics.

Doctors in Mainz-Bingen district are asked also to consider tularemia in patients with high fever and swollen lymph nodes into consideration, especially if the cause of these symptoms is unclear. Suspected cases are also subject to reporting under the Infection Protection Act at the Health Authority.