Darin Detwiler, a senior policy coordinator for food safety at STOP Foodborne Illness in Chicago and a graduate lecturer in regulatory affairs of the food industry at Northeastern University in Boston, writes in this op-ed:

I am deeply saddened to read about the deaths this year of a two young girls (one in Whatcom County and another in Portland,) both caused by E.coli.

I am deeply saddened to read about the deaths this year of a two young girls (one in Whatcom County and another in Portland,) both caused by E.coli.

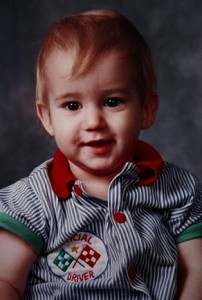

My 16-month-old son, Riley Detwiler, died from E.coli during the 1993 “Jack in the Box” outbreak. He became ill just as the Whatcom County Health Department warned of a child with E. coli at his daycare. The other child ate an undercooked, contaminated hamburger at the Bellingham restaurant. After noticing symptoms, I took Riley to St. Joseph’s Hospital where, after two days, doctors decided to airlift him to Children’s Hospital in Seattle.

Doctors removed most of his intestines, destroyed by foodborne pathogens, and collaborated with experts to make him healthy. I stood every day beside Riley’s little toddler body — dwarfed by wires and tubes. He laid in a coma for weeks until I held him one last time after he died. His poisoning and death made national headlines — even gaining the attention of President Clinton.

The 1993 “Jack in the Box” outbreak sickened over 650 people and took the lives of four young children. Today, many experts refer to that event as the “9/11” for the meat industry.

A pivotal moment in history, the attacks on 9/11 killed almost 3,000 people and resulted in sweeping changes in our national concept of homeland safety and our day to day security practices. The 1993 Jack in the Box E.coli outbreak should have been a pivotal moment in food safety. However, foodborne pathogens, according to the CDC, still cause 3,000 to 5,000 Americans to die each year. Even worse is the fact that Americans’ perception of food safety has not changed dramatically since then.

Two decades ago I hoped Riley’s death would lead to important national changes in industry, federal regulations, and in American’s awareness and behaviors. Unfortunately, I was wrong. Rarely has a week gone by when I have not heard or read about a food recall, an illness or a death from foodborne pathogens. Changes may be coming, but they will have come too late for the families of nearly 50,000 Americans who have died from food pathogens since Riley’s passing.

The CDC reports that at least 48 million Americans each year become ill from contaminated food leading to at least 128,000 hospitalizations. The CDC also stresses that for every single case of foodborne illness that gets reported, 38 cases go unreported.

Clearly, only the tip of this crisis is seen and reported. The majority of those made ill or who die from food poisoning are young children with immune systems not yet capable of fighting off the variety of foodborne pathogens found in America’s food supply.

Over the last 21 years, every time I see a news report of food recalls or of new illnesses and deaths from foodborne pathogens, I think about Riley — his smiling face, his few words and his few steps, his life cut short by problems in our food supply that persist to this day. These echoes of a needless loss come with the reminder that more needs to be done to prevent tragedies like this from erasing any sense of security and safety in the foods we eat and serve to our families.

Today, foodborne illnesses and deaths are associated with not only meat, but also with many other foods once considered completely safe. Foodborne pathogens are dangerous for all consumers and especially dangerous for those most susceptible to foodborne pathogens: the very young, elderly, pregnant, and those who are immune-compromised.

We may never understand exactly how the young girls from Lynden and Portland became sick and died from presumably safe food. What we should learn from these tragic deaths is that all foods pose the threat of illness or even death and that young consumers are most at risk. Also, foodborne pathogens are spread not only by consuming contaminated food, but also through physical contact with pathogens. My son died from E. coli without ever having eaten a hamburger in his life. Hand washing and prevention of cross-contamination are important. If we as a country can keep this in mind and stay vigilant, together we can minimize the spread and the threat of foodborne pathogens.