Of the U.S.’s 10 largest cities, Philadelphia is the only one that does not allow the public to see restaurant inspection reports for 30 days, time in which diners could unknowingly patronize restaurants with serious hygiene problems.

With the exception of Phoenix, which takes 72 hours to process its reports, the remaining major cities – including New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles – publish restaurant inspections immediately, according to a survey by Philly.com.

With the exception of Phoenix, which takes 72 hours to process its reports, the remaining major cities – including New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles – publish restaurant inspections immediately, according to a survey by Philly.com.

Pittsburgh posts its reports immediately. So do the counties of Bucks, Montgomery, and Chester, the last of which posts its findings on the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture database. That database includes most of the state, including many Delaware County municipalities, and it posts them without delay.

In New Jersey, Camden County posts results online within three to five business days; Burlington County does so at least as fast. Gloucester County’s website is updated monthly, with limited details.

The Philadelphia policy puzzles experts who wonder why the city would keep restaurant inspections private for so long.

“Give the restaurant a month to fix [the problems]?” asked Jim Chan, recently retired manager of Toronto’s DineSafe program.

“Is that fair to the public? Is that good health policy? No.”

“This seems like a strange protocol,” said Michael P. Doyle, director of the Center for Food Safety at the University of Georgia. “It certainly doesn’t help the customer.”

Andres Marin, professor of culinary arts at Community College of Philadelphia, said a weeklong delay might be acceptable to fix minor problems.

“But the question should be: What is the reason that we’re making these public?” Marin said. “We want to let the public know about the restaurant’s cleanliness and the way they’re handling the food. Withholding a report for 30 days makes no sense.”

Philadelphia Public Health Department spokesman Jeff Moran said reports are kept under wraps so owners of food establishments can challenge a sanitarian’s findings.

Philadelphia Public Health Department spokesman Jeff Moran said reports are kept under wraps so owners of food establishments can challenge a sanitarian’s findings.

How did the policy begin?

“My understanding is that this has been a long-standing policy, that it arose from [the] fact that [the] proprietor has [a] 30-day period to appeal an inspection,” city Health Commissioner James Buehler wrote via email Monday.

On Feb. 10, a city health employee inspected Joy Tsin Lau, a dim sum eatery with a banquet hall on Arch Street, and found improperly stored food, no soap in the employees’ restroom, and mouse droppings.

Her findings were kept secret. Seventeen days later, on Feb. 27, about 100 lawyers and law students were stricken with food poisoning after attending a banquet at the restaurant. Many were treated in city emergency rooms for what turned out to be norovirus, the leading cause of disease outbreaks from contaminated food in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. City inspectors do not test specifically for norovirus and other pathogens.

“No one would have gone there knowing about mouse droppings and the other sanitation violations,” said lawyer Richard Kim, who represents one of the sickened lawyers in a lawsuit against Joy Tsin Lau. “Nobody would have done that.”

Catherine Adams Hutt, a consultant for the National Restaurant Association, said the city’s 30-day policy was not responsible for sickening the lawyers.

“It doesn’t matter when an inspection report is posted,” Hutt said. “It’s the responsibility of the restaurant owner to correct the violations. There’s no excuse for a restaurant for food poisoning 17 days after an inspection.”

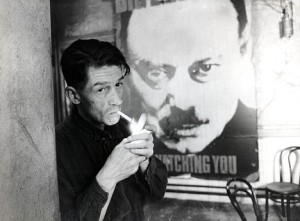

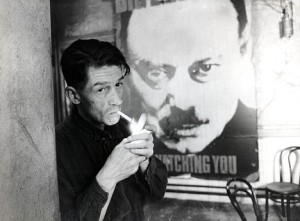

In a subsequent editorial, the disclosure this week by Philly.com that the city’s Health Department keeps its food-inspection reports secret for 30 days is the latest example of why the department is the Kremlin of local government.

Information is released on a need-to-know basis, if you can negotiate the maze set up to keep the public in the dark.

When it comes to food inspections, for instance, the department boasts of its transparency and posts online the full inspection reports on every institution it inspects, including the city’s 5,000 eat-in restaurants.

Now, Philly.com reveals that those reports are kept offline for 30 days, which happens to be just enough time for a restaurant to pass a reinspection.

Even if you do find the inspection reports (phila.gov/health/foodprotection) the department tells us too little by telling us too much. The raw reports are posted online, noting whether an establishment is in or out of compliance in 56 categories.

A regular member of the eating public would have trouble making sense of the reports, which are a jumble of bureaucratese.

One thing evident is that some restaurants are inspected again and again yet never can get their act together to pass an inspection.

Simpler public disclosure and enforcement with teeth would go a long way toward giving the public confidence – and that would benefit the entire food industry.

The Hoi Kee in Pinner, Middlesex, was temporarily shut and owner Shuai Zhang told to pay £800 costs.

The Hoi Kee in Pinner, Middlesex, was temporarily shut and owner Shuai Zhang told to pay £800 costs.