On 4/19/2016, the Wood County Health Department (WCHD) notified the Wisconsin Division of Public Health (DPH), Communicable Diseases Epidemiology Section (CDES) of two ill individuals who had both attended a company (Company A) banquet event at the Hotel Marshfield in Marshfield, WI on 4/16/16.

Onset of gastrointestinal symptoms in these individuals began early morning 4/18/2016. Appetizers, snacks, and entrees served during the event were prepared by Hotel Marshfield staff. Cupcakes were purchased from Bakery A, and cookies were provided by Company B. Leftover entrees from the banquet were boxed up immediately after the event and donated to Organization A (12 boxed meals total) where some were eaten by staff and residents of that organization.

Onset of gastrointestinal symptoms in these individuals began early morning 4/18/2016. Appetizers, snacks, and entrees served during the event were prepared by Hotel Marshfield staff. Cupcakes were purchased from Bakery A, and cookies were provided by Company B. Leftover entrees from the banquet were boxed up immediately after the event and donated to Organization A (12 boxed meals total) where some were eaten by staff and residents of that organization.

Upon recognition of a suspected outbreak, Organization A was asked by WCHD to hold the leftover food in their refrigerator and not serve it to anyone. WCHD collected a list of food and drink items served at the banquet from both the Hotel Marshfield manager and the Employee Relations Officer for Company A. CDES began creation of an investigation questionnaire, as well as an online survey to collect food and hotel exposure information from attendees. WCHD began dissemination of stool kits to ill banquet attendees and Hotel Marshfield employees to submit for laboratory testing.

This investigation identified a foodborne outbreak of norovirus gastroenteritis associated with consuming food from a banquet event held at the Hotel Marshfield banquet facility in Marshfield, WI on 4/16/2016. The causative agent was Norovirus genogroup II.17B (Kawasaki). Confirmed and probable cases were identified among banquet attendees and employees of Hotel Marshfield.

Based on the epidemiologic, laboratory, and environmental evidence gathered during this outbreak, improper food handling by a Hotel Marshfield employee who was infected with norovirus is the most likely cause of this outbreak. Because specific food items were identified that were associated with higher risk of illness and all of these items were served on the same plate, this suggests the ill employee was a chef rather than a server or bartender. The challenge of being short-staffed in the banquet kitchen on the day of the banquet may have contributed to a breakdown in hand hygiene or glove use.

The pattern of illness onset dates and times in the epidemic curve supports the conclusion that exposure to the virus occurred at the same time among banquet attendees and hotel staff. This means that the virus was not introduced to the hotel by an ill banquet attendee. Although one banquet attendee reported becoming ill during the event, the epidemic curve indicates a point source exposure consistent with a foodborne outbreak, rather than the pattern of illnesses typically seen with person-to-person transmission from an ill attendee. Since ill attendees do not come in contact with kitchen staff, outbreaks where both food workers and attendees are ill at the same time generally indicate the food worker was the source, rather than a victim.

Additionally, the same strain of norovirus, norovirus GII.17B (Kawasaki) was isolated from both food workers and banquet attendees. The Kawasaki strain is a rare strain of norovirus only recently introduced to the United States in the last five years.7 In Wisconsin, it tends to be associated with foodborne outbreak settings rather than person-to-person transmission in the community; during 2015- 2016, 62.5% of the outbreaks caused by the Kawasaki strain in Wisconsin were foodborne.8 The rarity of the strain, its recovery from both employees (including Chef A) and attendees, and the fact that the same strain was identified in all norovirus positive specimens support the conclusion the illnesses were all acquired from a single source.

Chef A reported illness onset at 1:45am on the night of the banquet (4/16/16) while the majority of other illnesses began in the evening of the next day. The length of Chef A’s incubation period (time between exposure and start of symptoms) was 7.75 hours, which is shorter than the range of 10‐50 hours observed during volunteer studies of norovirus infection where exact time of exposure is known,9,10 as well as the median incubation period length of 32.5 hours observed in this outbreak. Assuming the onset date and time of Chef A’s illness was accurately reported, this indicates Chef A was likely exposed to the virus 1-2 days prior to the banquet (not at the same time as banquet attendees and other staff). Although Chef A’s symptoms did not begin until after the banquet was over, shedding of norovirus in the stool of infected asymptomatic individuals has been documented11 and it was likely Chef A was shedding virus at the time he/she was preparing and plating the food for the banquet. Additionally, carriage and shedding of norovirus has been documented in individuals who never develop symptoms.12 It is also possible that an unidentified asymptomatic shedding employee could have served as a source of contamination during food prep, or that an ill employee did not accurately disclose his/her illness status and onset date/time.

Chef A reported illness onset at 1:45am on the night of the banquet (4/16/16) while the majority of other illnesses began in the evening of the next day. The length of Chef A’s incubation period (time between exposure and start of symptoms) was 7.75 hours, which is shorter than the range of 10‐50 hours observed during volunteer studies of norovirus infection where exact time of exposure is known,9,10 as well as the median incubation period length of 32.5 hours observed in this outbreak. Assuming the onset date and time of Chef A’s illness was accurately reported, this indicates Chef A was likely exposed to the virus 1-2 days prior to the banquet (not at the same time as banquet attendees and other staff). Although Chef A’s symptoms did not begin until after the banquet was over, shedding of norovirus in the stool of infected asymptomatic individuals has been documented11 and it was likely Chef A was shedding virus at the time he/she was preparing and plating the food for the banquet. Additionally, carriage and shedding of norovirus has been documented in individuals who never develop symptoms.12 It is also possible that an unidentified asymptomatic shedding employee could have served as a source of contamination during food prep, or that an ill employee did not accurately disclose his/her illness status and onset date/time.

While Front of House staff were involved in adding croutons to salads, none of these items were statistically associated with illness. Only items that were prepared and finished in the kitchen were statistically associated with illness, increasing the likelihood the contamination event occurred during banquet meal preparation. If a banquet server was the source, we would expect to see no statistically significant association with a specific food item because all types of entrée plates would be handled by the ill individual.

Results of the case-control study showed that individuals who consumed the New York strip steak (served with a red wine reduction), buttery garlic chive mashed potatoes, and glazed carrots were more than two times more likely to become ill than those who did not. These three items were plated together on the same plate. A significant statistical association with illness existed for each item individually and for all three items combined. No other food or beverage items were statistically associated with illness. The fact that all food items with a significant association with illness were cooked items (except the chopped parsley garnish and honey glaze) suggests that contamination occurred after the items were cooked. Foodborne norovirus outbreaks commonly involve food items that are handled and served raw, such as salads and fruit. The only raw ingredients on the steak plates reported by the establishment were chopped fresh parsley used as garnish and the honey squeezed onto the carrots after reheating. Since the chef stated that the same parsley was used as garnish for all three entrees, if the parsley was contaminated at its source (in the field), we would expect to see no statistically significant food item, since all entrees would have contained the same parsley. However, the fact that only the steak plate was statistically associated with illness suggests contamination by food worker during kitchen prep is more likely than contamination in the field. Contamination could have been introduced if parsley was chopped while wearing gloves, but then added to the steak plates by an ungloved hand. Alternatively, the parsley may have only been added to the steak plates. Also, contamination could have also been introduced if the honey squeeze bottle or bottle nozzle was contaminated with norovirus.

Although no additional illnesses were reported among attendees of subsequent banquets, one secondary case occurred in an employee, suggesting person-to-person transmission or transmission from contact with contaminated environmental surfaces also occurred among staff the day after the banquet. Chef A continued to work the next couple days while symptomatic with diarrhea and could have contaminated surfaces or transferred the virus via contact, serving as the source of infection for the secondary case identified among staff. Hotel employees with primary cases who became ill but did not consume banquet food may have been exposed to contaminated food during serving, table clearing, or cleaning, or to contaminated surfaces such as tables in kitchen prep areas, sinks, bathrooms, or door handles.

Several contributing factors were identified during this outbreak investigation, and multiple violations of Wisconsin Food Code which could contribute to the likelihood of an outbreak occurring were observed during the on-site assessments conducted by WCHD sanitarians. Bare-handed contact of ready-to-eat food items by food workers was observed multiple times during the same visit, suggesting that bare- handed contact occurs frequently during routine food prep activities at the facility. The facility did not have any formal written employee illness, hand washing, or glove use policies. Review of the employees’ work schedules in conjunction with their illness onset and resolution dates indicated that Chef A worked preparing food for more banquets at the facility while symptomatic with diarrhea, which violates Wisconsin Food Code. Additionally, hotel employee restrooms did not have functioning fans and are located near (approx. 15ft) food preparation areas. While the case-control study results point to contamination of specific food items as the source of illness during this outbreak, the close proximity of the employee bathrooms to prep areas could contribute to kitchen contamination and future outbreaks.

RECOMMENDATIONS

According to the CDC, while there is no vaccine to prevent norovirus infection, illness can be prevented through proper hand hygiene; washing fruits and vegetables and cooking seafood thoroughly before consuming; avoiding food preparation and caring for others when sick; cleansing and disinfecting contaminated surfaces; and carefully washing laundry.

Individuals who work in the food service industry should be aware of practices that can prevent the spread of noroviruses:

- not preparing food for others when sick and for at least 48 hours after symptoms stop,

- practicing proper hand hygiene,

- rinsing fruits and vegetables and cooking shellfish,

- regularly cleaning and sanitizing kitchen utensils, counters, and surfaces, and

- carefully washing table linens, napkins, and other laundry.

It is particularly important for food establishment employees to inform their manager when they are ill and to not work while sick with gastroenteritis and for at least 48 hours following recovery. Complying with this recommendation means that employees need to be both aware of it and have the motivation and responsibility to comply with it.

The following recommendations were developed for Hotel Marshfield following the assessment conducted on 4/20 and 4/21/2016:

- Review internal procedures regarding employee illness, glove use, and hand washing to ensure they are consistent with standard food safety regulations, and create written policies outlining these procedures.

- Review and update sick leave policy for management and employees.

- All personnel, including management, should undergo comprehensive food handling training that includes at a minimum: personal hygiene, proper use of disposable gloves, and employee illness policies to ensure complete understanding.

Consider installing negative pressure ceiling fans in employee restrooms to minimize movement of aerosolized particles into the kitchen, or, discontinue use of the employee restrooms in the kitchen area.

As a result of these recommendations, the hotel has reviewed their procedures for reporting illness, glove use, and hand washing with all staff. The sick leave policy has been reviewed with all staff, and the fact that all staff that earn paid time off (sick leave) has been reinforced. The WCHD conducted an onsite food safety training at Hotel Marshfield that discussed personal hygiene, glove use, and employee illness, as well as other risk factors for foodborne illness. The information provided during the training presentation and via brochures has been incorporated into the hotel’s employee training program.

The employee restroom fans were verified operational (low-flow, constant-on fans) and the employee restroom doors have had spring hinges installed to self-close and keep closed. Ready-to-use spray bottles of bleach solution have been added as an additional option for sanitizing in the kitchen.

Norovirus Outbreak Associated with a Banquet at Hotel Marshfield

4.nov.16

Wood County Health Department , Wisconsin Division of Public Health Bureau of Communicable Diseases

https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/3190897/Final-Investigation-Report-Wood-Hotel-Marshfield.pdf

There was some totally unscientific answer about how these sprouts were special because they came from a different place and they disappeared from the sick persons menu for a few weeks.

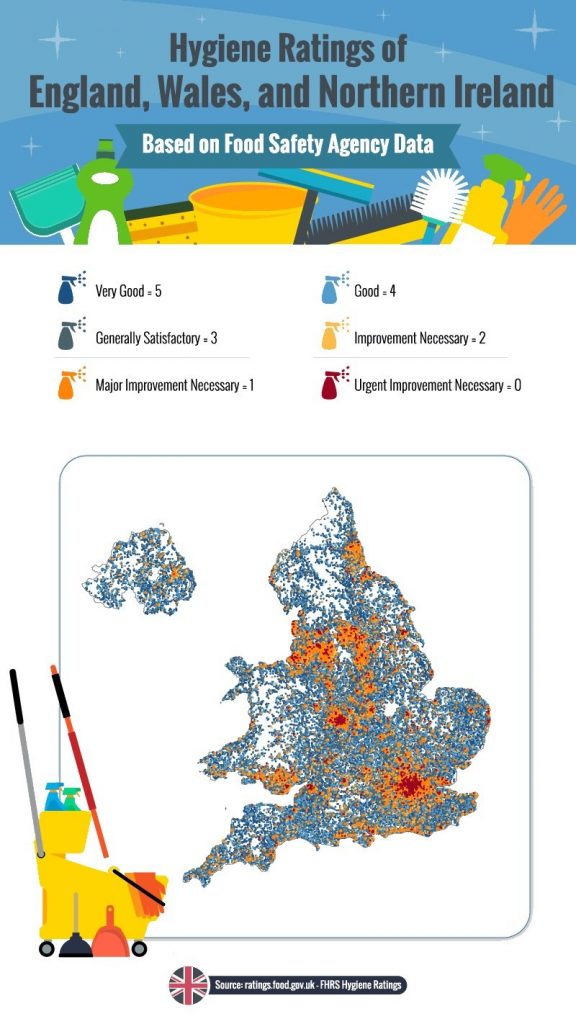

There was some totally unscientific answer about how these sprouts were special because they came from a different place and they disappeared from the sick persons menu for a few weeks. And 205 are ranked as two – improvement necessary. They include six hospitals and about 100 care homes. Among those given the ranking of two was Glenfield Hospital in Leicester.

And 205 are ranked as two – improvement necessary. They include six hospitals and about 100 care homes. Among those given the ranking of two was Glenfield Hospital in Leicester.