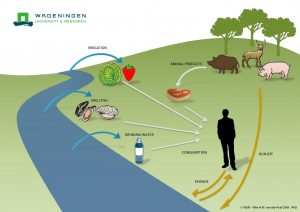

Nearly one-half of foodborne illnesses in the United States can be attributed to fresh produce consumption. The preharvest stage of production presents a critical opportunity to prevent produce contamination in the field from contaminating postharvest operations and exposing consumers to foodborne pathogens. One produce-contamination route that is not often explored is the transfer of pathogens in the soil to edible portions of crops via splash water.

We report here on the results from multiple field and microcosm experiments examining the potential for Salmonella contamination of produce crops via splash water, and the effect of soil moisture content on Salmonella survival in soil and concentration in splash water. In field and microcosm experiments, we detected Salmonella for up to 8 to 10 days after inoculation in soil and on produce. Salmonella and suspended solids were detected in splash water at heights of up to 80 cm from the soil surface. Soil-moisture conditions before the splash event influenced the detection of Salmonella on crops after the splash events—Salmonella concentrations on produce after rainfall were significantly higher in wet plots than in dry plots (geometric mean difference = 0.43 CFU/g; P = 0.03). Similarly, concentrations of Salmonella in splash water in wet plots trended higher than concentrations from dry plots (geometric mean difference = 0.67 CFU/100 mL; P = 0.04).

We report here on the results from multiple field and microcosm experiments examining the potential for Salmonella contamination of produce crops via splash water, and the effect of soil moisture content on Salmonella survival in soil and concentration in splash water. In field and microcosm experiments, we detected Salmonella for up to 8 to 10 days after inoculation in soil and on produce. Salmonella and suspended solids were detected in splash water at heights of up to 80 cm from the soil surface. Soil-moisture conditions before the splash event influenced the detection of Salmonella on crops after the splash events—Salmonella concentrations on produce after rainfall were significantly higher in wet plots than in dry plots (geometric mean difference = 0.43 CFU/g; P = 0.03). Similarly, concentrations of Salmonella in splash water in wet plots trended higher than concentrations from dry plots (geometric mean difference = 0.67 CFU/100 mL; P = 0.04).

These results indicate that splash transfer of Salmonella from soil onto crops can occur and that antecedent soil-moisture content may mediate the efficiency of microbial transfer. Splash transfer of Salmonella may, therefore, pose a hazard to produce safety. The potential for the risk of splash should be further explored in agricultural regions in which Salmonella and other pathogens are present in soil. These results will help inform the assessment of produce safety risk and the development of management practices for the mitigation of produce contamination.

Salmonella survival in soil and transfer onto produce via splash events

December 2019

Journal of Food Protection vol. 82 no. 12

DEBBIE LEE,1 MOUKARAM TERTULIANO,2 CASEY HARRIS,2† GEORGE VELLIDIS,2 KAREN LEVY,1* and TIMOTHY COOLONG3

https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-19-066

https://jfoodprotection.org/doi/abs/10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-19-066?af=R