Between August and December 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and multiple state and federal partners were involved in an outbreak investigation related to E. coli O157:H7 illnesses and the consumption of leafy greens. The outbreak, which caused 40 reported domestic illnesses, was linked via whole genome sequencing (WGS) and geography to outbreaks traced back to the California growing region associated with the consumption of leafy greens in 2019 and 2018. FDA, alongside state and federal partners, investigated the outbreak to identify potential contributing factors that may have led to leafy green contamination with E. coli O157:H7. The E. coli O157:H7 outbreak strain was identified in a cattle feces composite sample taken alongside a road approximately 1.3 miles upslope from a produce farm with multiple fields tied to the outbreaks by the traceback investigations. In addition, several potential contributing factors to the 2020 leafy greens outbreak were identified.

Isolates within this cluster of illnesses are part of a reoccurring strain of concern and are associated with outbreaks that have occurred in leafy greens each fall since 2017. The two most recent outbreaks associated with this strain were an outbreak in 2018 (linked to romaine lettuce from the Santa Maria growing region of California) and an outbreak in 2019 (linked to romaine lettuce from the Salinas growing region of California). Clinical isolates from cases in this 2020 outbreak appear more closely related to those from the 2019 outbreak than the 2018 outbreak. In addition, several specific food and environmental isolates that appear to be highly related to this 2020 outbreak include a fecal-soil composite sample collected by FDA in February 2020 from the Salinas growing region and two leafy green samples collected in 2019 by state partners as a part of the 2019 investigation that traced back to the Salinas growing region.

Isolates within this cluster of illnesses are part of a reoccurring strain of concern and are associated with outbreaks that have occurred in leafy greens each fall since 2017. The two most recent outbreaks associated with this strain were an outbreak in 2018 (linked to romaine lettuce from the Santa Maria growing region of California) and an outbreak in 2019 (linked to romaine lettuce from the Salinas growing region of California). Clinical isolates from cases in this 2020 outbreak appear more closely related to those from the 2019 outbreak than the 2018 outbreak. In addition, several specific food and environmental isolates that appear to be highly related to this 2020 outbreak include a fecal-soil composite sample collected by FDA in February 2020 from the Salinas growing region and two leafy green samples collected in 2019 by state partners as a part of the 2019 investigation that traced back to the Salinas growing region.

As part of this investigation, tracebacks of leafy greens consumed by ten ill individuals from eleven points of service were conducted. Although that traceback investigation was based on a relatively small number of the total cases, it was based on those cases which presented the strongest evidence via purchase card information, invoices, bills of lading, and electronic data. The traceback investigation identified the Salinas growing region of California as a geographical region of interest.

In light of this most recent finding, combined with previous outbreak investigation findings in the region, FDA has identified key trends regarding the issues of a reoccurring strain, a reoccurring region, and reoccurring issues around adjacent and nearby land use of primary importance in understanding the contamination of leafy greens by E. coli O157:H7 that occurred in 2020 and previous years.

FDA also recognizes the interconnection between people, animals, plants, and their shared environment when it comes to public health outcomes. As such, we strongly encourage collaboration among various groups in the broader agricultural community (i.e. livestock owners; leafy greens growers, state and federal government agencies, and academia) to address this issue. With this collaboration, the agricultural community, alongside academic and government partners, can work to identify and implement measures to prevent contamination of leafy greens. FDA recommends that these parties participate in efforts to understand and address the challenge of successful coexistence of various types of agricultural industries to ensure food safety and protect consumers against foodborne illnesses.

Frank Yiannas, Deputy Commissioner for Food Policy and Response – Food and Drug Administration said in a release that as part of our ongoing efforts to combat foodborne illness, today the U.S. Food and Drug Administration published a report on the investigation into the Fall 2020 outbreak of Shiga Toxin-Producing E. coli (STEC) O157:H7 illnesses linked to the consumption of leafy greens grown in the California Central Coast. The report describes findings from the investigation, as well as trends that are key to understanding leafy green outbreaks that are linked to the California Central Coast growing region, specifically encompassing the Salinas Valley and Santa Maria growing areas every fall since 2017.

Frank Yiannas, Deputy Commissioner for Food Policy and Response – Food and Drug Administration said in a release that as part of our ongoing efforts to combat foodborne illness, today the U.S. Food and Drug Administration published a report on the investigation into the Fall 2020 outbreak of Shiga Toxin-Producing E. coli (STEC) O157:H7 illnesses linked to the consumption of leafy greens grown in the California Central Coast. The report describes findings from the investigation, as well as trends that are key to understanding leafy green outbreaks that are linked to the California Central Coast growing region, specifically encompassing the Salinas Valley and Santa Maria growing areas every fall since 2017.

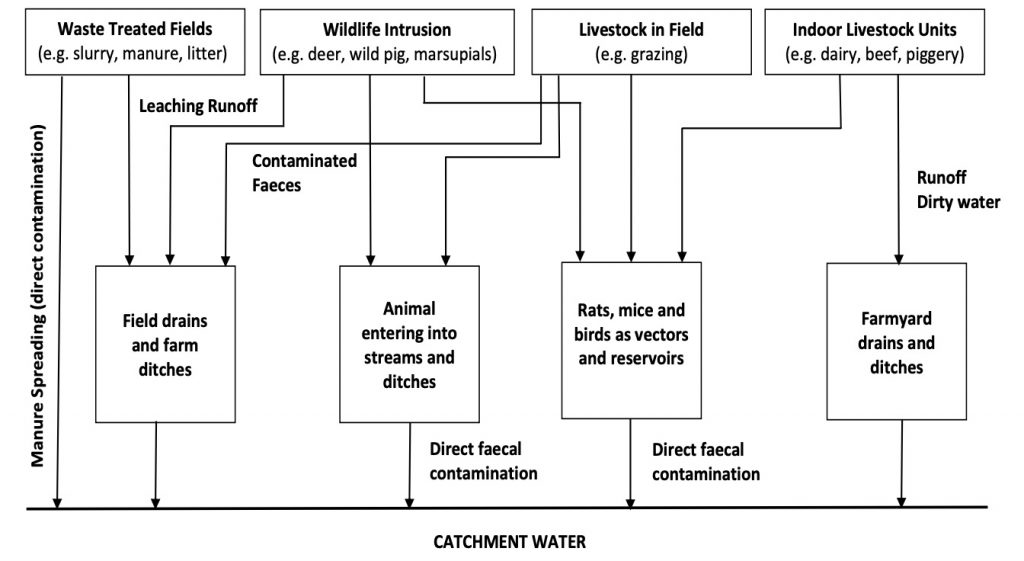

We released our preliminary findings earlier this year that noted this investigation found the outbreak strain in a sample of cattle feces collected on a roadside about a mile upslope from a produce farm. This finding drew our attention once again to the role that cattle grazing on agricultural lands near leafy greens fields could have on increasing the risk of produce contamination, where contamination could be spread by water, wind or other means. In fact, the findings of foodborne illness outbreak investigations since 2013 suggest that a likely contributing factor for contamination of leafy greens has been the proximity of cattle. Cattle have been repeatedly demonstrated to be a persistent source of pathogenic E. coli, including E. coli O157:H7.

Considering this, we recommend that all growers be aware of and consider adjacent land use practices, especially as it relates to the presence of livestock, and the interface between farmland, rangeland and other agricultural areas, and conduct appropriate risk assessments and implement risk mitigation strategies, where appropriate. Increasing awareness around adjacent land use is one of the specific goals of the Leafy Greens Action Plan we released last March, which we’re also announcing is being updated today to include new activities for 2021.

During our analysis of outbreaks that have occurred each fall since 2017, we have determined there are three key trends in the contamination of leafy greens by E. coli O157:H7 in recent years: a reoccurring strain, reoccurring region and reoccurring issues with activities on adjacent land. The 2020 E. coli O157:H7 outbreak associated with leafy greens represents the latest in a repeated series of outbreaks associated with leafy greens that originated in the Central Coast of California (encompassing Salinas Valley and Santa Maria) growing region (that’s me and Frank and the woman who wants to divorce me in our Kansas kitchen, 10 years ago)

During our analysis of outbreaks that have occurred each fall since 2017, we have determined there are three key trends in the contamination of leafy greens by E. coli O157:H7 in recent years: a reoccurring strain, reoccurring region and reoccurring issues with activities on adjacent land. The 2020 E. coli O157:H7 outbreak associated with leafy greens represents the latest in a repeated series of outbreaks associated with leafy greens that originated in the Central Coast of California (encompassing Salinas Valley and Santa Maria) growing region (that’s me and Frank and the woman who wants to divorce me in our Kansas kitchen, 10 years ago)

In the investigation, the FDA recommends that growers of leafy greens in the California Central Coast Growing Region consider this reoccurring E. coli strain a reasonably foreseeable hazard, and specifically of concern in the South Monterey County area of the Salinas Valley. It is important to note that farms covered by the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) Produce Safety Rule are required to implement science and risk-based preventive measures in the rule, which includes practices that prevent the introduction of known or reasonably foreseeable hazards into or onto produce.

The FDA also recommends that the agricultural community in the California Central Coast growing region work to identify where this reoccurring strain of pathogenic E. coli is persisting and the likely routes of leafy green contamination with STEC. Specifically, we have outlined specific recommendations in our investigation report for growers in the California Central Coast leafy greens region. Those recommendations include participation in the California Longitudinal Study and the California Agricultural Neighbors workgroup. When pathogens are identified through microbiological surveys, pre-harvest or post-harvest testing, we recommend growers implement industry-led root cause analyses to determine how the contamination likely occurred and then implement appropriate prevention and verification measures.

In response, Tim York wrote in The Packer that on April 16 the California LGMA Board took decisive action to endorse pre-harvest testing guidance. The guidance recommends pre-harvest testing specifically when leafy greens are being farmed in proximity to animal operations.

It’s the intention of the board to include pre-harvest testing as part of the LGMA audit checklist so the government can verify that all LGMA members are in compliance.

This is the first time an entire commodity group will be required to conduct pre-harvest testing.

This is a big deal, but a necessary response to the recent U.S. Food and Drug Administration report on outbreaks associated with lettuce in 2020. The findings and regulatory language used by FDA in this report were nothing short of a warning shot that calls on our industry to do more to stop outbreaks.

And so, we must do more.

Updating LGMA’s required food safety practices is an involved process that seeks input from scientists, food safety experts and the public. No other entity is capable of making such widespread change as quickly as we can.<

Some weeks ago, in the first piece I wrote for The Packer as CEO of the California LGMA, I stressed the need for collaboration with the retail and foodservice buying community, noting that we must lean on each other to make needed improvements together. And now, I am asking for your help.

Updating LGMA’s required food safety practices is an involved process that seeks input from scientists, food safety experts and the public. No other entity is capable of making such widespread change as quickly as we can.