The voluntary quality control system widely used in the nation’s $1 trillion domestic food industry is rife with conflicts of interest, inexperienced auditors and cursory inspections that produce inflated ratings, according to food retail executives and other industry experts.

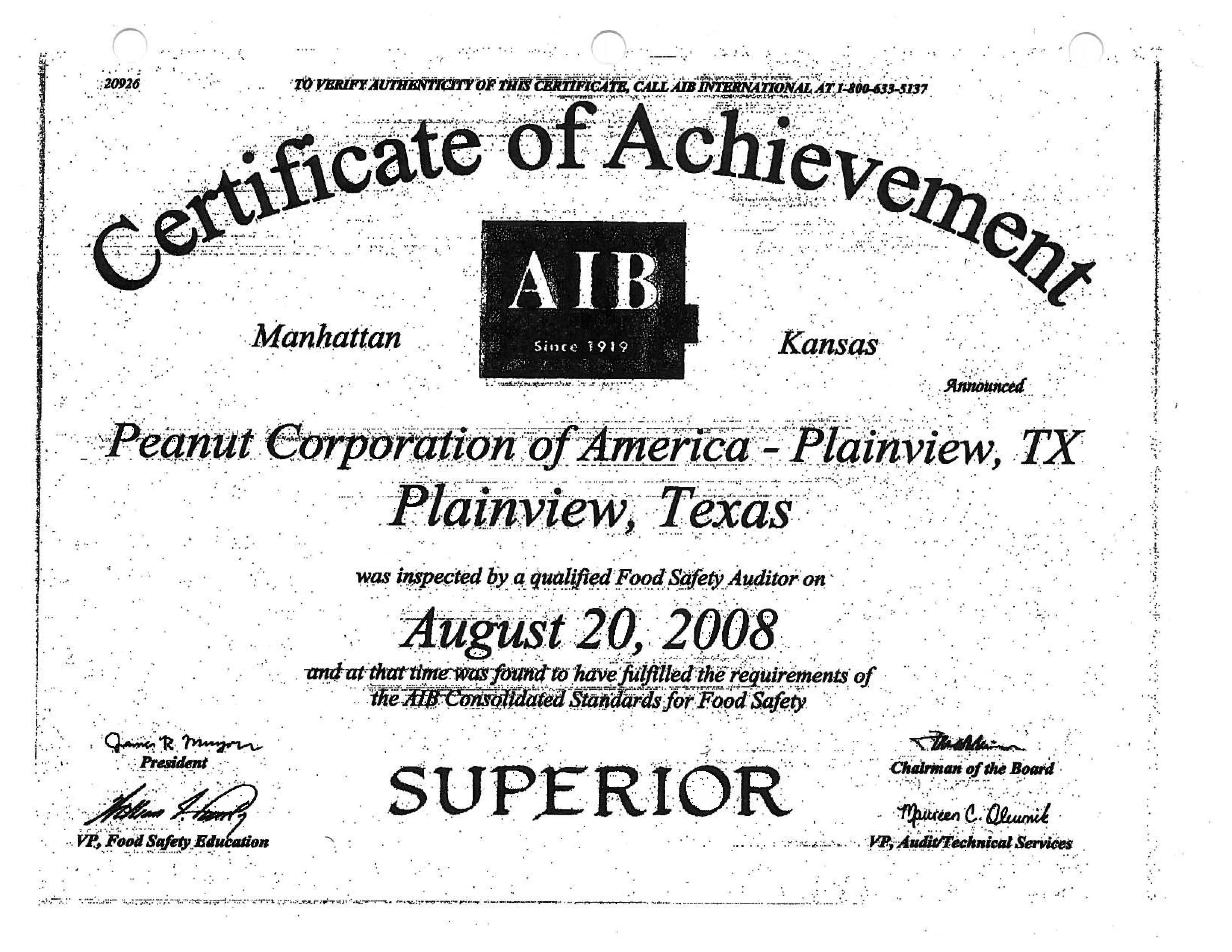

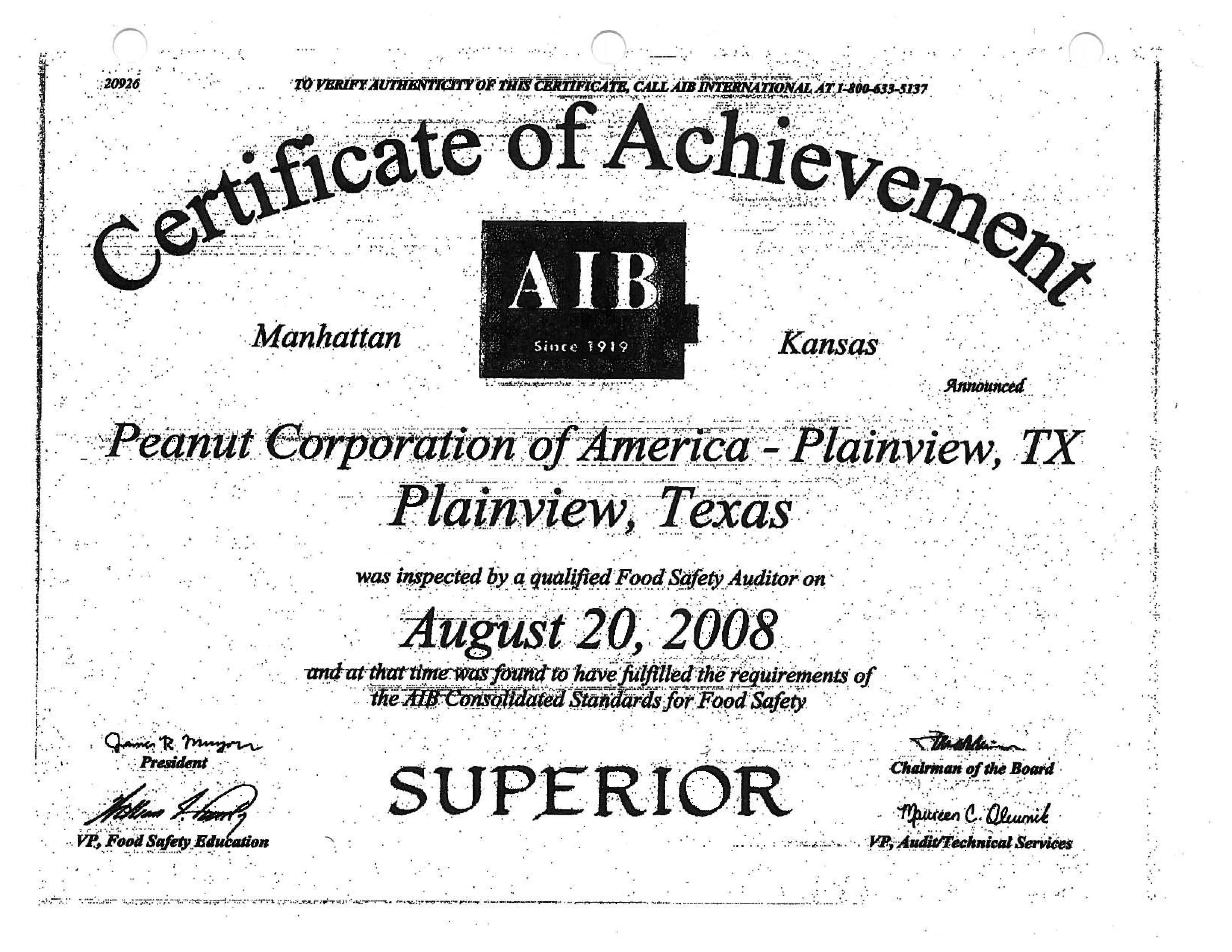

I’ve been saying that for a long time, but this is the Washington Post version, published this morning. I especially like the pictures of the  Montgomery Burns Awards for Outstanding Achievement in the Field of Excellence, courtesy of AIB, the Manhattan, Kansas-based audiots that gave a stellar rating to PCA and Wright Eggs just prior to terrible food safety outbreaks and revelations of awful production conditions (see below).

Montgomery Burns Awards for Outstanding Achievement in the Field of Excellence, courtesy of AIB, the Manhattan, Kansas-based audiots that gave a stellar rating to PCA and Wright Eggs just prior to terrible food safety outbreaks and revelations of awful production conditions (see below).

The system has developed primarily because large chain stores and food producers, such as Kellogg’s, want assurances about the products they place on their shelves and the ingredients they use in making food. To get that, they often require that their suppliers undergo regular inspections by independent auditors. This all takes place outside any government involvement and without any signals – stamps of approval, for instance – to consumers. (That’s four-year-old Zoe Warren, right, of Bethesda, who was hospitalized in 2007 after contracting salmonella poisoning after eating a chicken pot pie. The photo is by Susan Biddle for the Washington Post.)

The third-party food safety audit scheme that processors and retailers insisted upon is, in many cases, no better than a financial Ponzi scheme. .jpg) The vast number of facilities and suppliers means audits are required, but people have been replaced by paper.

The vast number of facilities and suppliers means audits are required, but people have been replaced by paper.

In fact, most foodmakers, even those with problems, sail through their inspections, said Mansour Samadpour, who owns a food-testing firm that does not perform audits. "I have not seen a single company that has had an outbreak or recall that didn’t have a series of audits with really high scores.”

Third-party food audits, like restaurant inspection, are a snapshot in time. Given the international sourcing of ingredients, audits are a requirement, but so is internal food safety intelligence to make sense of audits that are useful and audits that are chicken poop.

Industry experts say some "third-party" inspections can be rigorous. Those that audit using internationally recognized private benchmarks "are much  more thorough," said Robert Brackett, former senior vice president of the Grocery Manufacturers Association. "But they’re less likely to be used because they are much more expensive."

more thorough," said Robert Brackett, former senior vice president of the Grocery Manufacturers Association. "But they’re less likely to be used because they are much more expensive."

Audits, inspections, training and systems are no substitute for developing a strong food safety culture, farm-to-fork, and marketing food safety directly to consumers rather than the local/natural/organic hucksterism is a way to further reinforce the food safety culture.

Will Daniels, who oversees food safety for Earthbound Farm, the folks who brought E. coli O157:H7 in bagged spinach in 2006 that sickened 199 and killed four, said, Earthbound regularly received top ratings in third-party audits, including one exactly a month before the tainted spinach was processed, adding,

"No one should rely on third-party audits to insure food safety."

“… if the incentive is to pass with flying colors, it creates a disincentive to air your dirty laundry and get dinged and lose a customer over it.”

After the E. coli outbreak, Earthbound put in place an aggressive testing and safety program that includes outside audits but also requires Earthbound’s own inspectors to show up unannounced to check suppliers. The company tests its greens for pathogens when they arrive from farms and again when they are packaged.

Too bad Earthbound didn’t figure all this out after the 28 other outbreaks involving leafy greens prior to the deadly 2006 outbreak.

Cost is another factor.

Food companies often choose the cheapest auditors to minimize the added expense of inspections, which range from about $1,000 to more than $25,000.

The foodmakers can prepare for audits because they often know when inspectors will show up.

And auditors have a range of experience and qualifications, from recent college graduates to retired food industry veterans. They sometimes walk through a plant, ticking off a checklist to produce a score, Samadpour said. Basic inspections do not typically include microbial sampling for bacteria.

In a written response to questions, Brian Soddy, AIB‘s vice president of marketing and sales, said company audits are intended to give food  manufacturers "guidance and education for improvement."

manufacturers "guidance and education for improvement."

Producers have the ultimate responsibility, he said, adding that the audits are voluntary and not intended to replace any FDA regulatory inspections.

AIB said last week that it is reevaluating its "superior" and "excellent" rating systems because they "have led to confusion in the wake of recent incidents," Soddy wrote.

Some retailers include inspections as just one piece of their safety programs.

Costco, for example, has its own inspectors but also requires its estimated 4,000 food vendors to have their products inspected according to a detailed 10-page list of criteria. Private auditors must X-ray all products for "sticks and stones, bones in seafood – anything you can think of that might be in hot dogs, baked goods, outside of produce," said Craig Wilson, Costco’s assistant vice president for food safety and quality assurance.

Costco maintains an approved list of about nine audit firms. The list does not include AIB.

Wal-Mart requires suppliers of private-label food products sold in its stores and Sam’s Club to be audited using private internationally recognized standards.

In addition to conducting its own product testing, Giant Food requires its vendors to be audited from a list of about a dozen approved firms.

Maybe Australians haven’t heard about that one: sometimes the news takes awhile by steamship.

Maybe Australians haven’t heard about that one: sometimes the news takes awhile by steamship.

present, illness can result, according to the USDA. So using a microwave that delivers even heating is important.

present, illness can result, according to the USDA. So using a microwave that delivers even heating is important. .jpg)

Montgomery Burns Awards for Outstanding Achievement in the Field of Excellence, courtesy of AIB, the Manhattan, Kansas-based audiots that gave a stellar rating to PCA and Wright Eggs just prior to terrible food safety outbreaks and revelations of awful production conditions (see below).

Montgomery Burns Awards for Outstanding Achievement in the Field of Excellence, courtesy of AIB, the Manhattan, Kansas-based audiots that gave a stellar rating to PCA and Wright Eggs just prior to terrible food safety outbreaks and revelations of awful production conditions (see below)..jpg) The vast number of facilities and suppliers means audits are required, but people have been replaced by paper.

The vast number of facilities and suppliers means audits are required, but people have been replaced by paper. more thorough," said Robert Brackett, former senior vice president of the Grocery Manufacturers Association. "But they’re less likely to be used because they are much more expensive."

more thorough," said Robert Brackett, former senior vice president of the Grocery Manufacturers Association. "But they’re less likely to be used because they are much more expensive." manufacturers "guidance and education for improvement."

manufacturers "guidance and education for improvement."(1).jpg) On June 22, 2010, Ontario’s Chief Medical Officer of Health said

On June 22, 2010, Ontario’s Chief Medical Officer of Health said(1).jpg) sick from a microwaved chicken nugget and represent the folks they work for and ask:

sick from a microwaved chicken nugget and represent the folks they work for and ask: Marie Callender‘s Cheesy Chicken & Rice frozen meal.

Marie Callender‘s Cheesy Chicken & Rice frozen meal. to be the kill step.”

to be the kill step.” A quest to find what he calls

A quest to find what he calls

(BTW,

(BTW, .jpg) And in a staggering example of corporate arrogance coupled with blame-the-consumer, Jim Seiple, a food safety official with the Blackstone unit that makes Swanson and Hungry-Man pot pies, said pot pie instructions have built-in margins of error, and the risk to consumers depended on

And in a staggering example of corporate arrogance coupled with blame-the-consumer, Jim Seiple, a food safety official with the Blackstone unit that makes Swanson and Hungry-Man pot pies, said pot pie instructions have built-in margins of error, and the risk to consumers depended on