Michael Pollan is an entertainer from a long line of American hucksters.

He’s not a professor, he’s a decent writer of food porn.

(Those with the least qualifications most actively seek the perceived credibility of a title.)

(Those with the least qualifications most actively seek the perceived credibility of a title.)

When his biggest soundbite is “I’d never eat a refrigerated tomato,” the absolutism shines through like any other spoiled demagogue.

Dan Charles of NPR fell into the gotta-be-cool trap without knowing shit, but eventually admitted it.

Charles says, There’s a laboratory at the University of University of Florida, in Gainesville, that has been at the forefront of research on tomato taste. Scientists there have been studying the chemical makeup of great-tasting tomatoes, as well as the not-so-great tasting ones at supermarkets.

“There’s a lot of things wrong with tomatoes right now,” says Denise Tieman, a research associate professor there. “We’re trying to fix them, or at least figure out what’s going wrong.”

These researchers studied this refrigeration question. They looked at what happened when a tomato goes into your kitchen fridge, or into the tomato industry’s refrigerated trucks and storage rooms.

Some components of a tomato’s flavor were unaffected, such as sugars and acids. But they found that after seven days of refrigeration, tomatoes had lower levels of certain chemicals that Tieman says are really important. These so-called aroma compounds easily vaporize. “That’s what gives the tomato its distinctive aroma and flavor,” she says.

The researchers also gave chilled and unchilled tomatoes to dozens of people to evaluate, in blind taste tests, “and they could definitely tell the difference,” says Tieman. The tomatoes that weren’t chilled got better ratings.

The scientists also figured out how chilling reduced flavor; cold temperatures actually turned off specific genes, and that, in turn cut down production of these flavor compounds.

Tieman speculates that someday scientists will figure out how to keep those genes turned on, even when chilled, so the tomato industry can have it both ways: They can refrigerate tomatoes to extend shelf life, without losing flavor.

Thankfully, chilling didn’t seem to affect nutrition – the chilled tomatoes were just as nutritious as the non-refrigerated ones.

Thankfully, chilling didn’t seem to affect nutrition – the chilled tomatoes were just as nutritious as the non-refrigerated ones.

The new findings appear in this week’s issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

As significant as the results are, they probably won’t end the great tomato refrigeration debate.

“It’s not so clear cut,” says Daniel Gritzer, culinary director at SeriousEats.com, a food website. Two years ago, he did a series of blind taste tests with many different tomatoes, in New York and in California.

“Sometimes I found that the refrigerator is, in fact, your best bet,” says Gritzer.

That’s especially true for a tomato that’s already ripe and at peak flavor, he says. If you let that tomato sit on your counter, it’ll end up tasting worse.

Gritzer wrote a long blog post, detailing his results, and got a flood of reaction. “Some people wrote to say, ‘Hey, this is what I’ve always found, I’m so glad you wrote this,'” Gritzer says. “And then, a lot of people pushed back saying, ‘You’re insane, you don’t know what you’re talking about.'”

And when the hockey kids call me Doug, I say that’s Dr. Doug, I didn’t spend six years in evil hockey coaching land to be called Mister.

.jpg) a Salt Lake City restaurant/deli.

a Salt Lake City restaurant/deli.

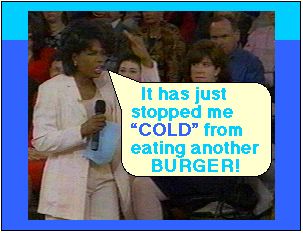

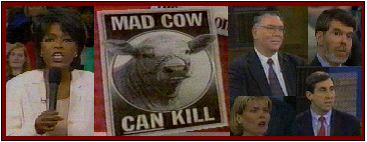

commercial. Such was the power of Oprah.

commercial. Such was the power of Oprah. expediting regulations prohibiting ruminant protein in ruminant feeds, boosting

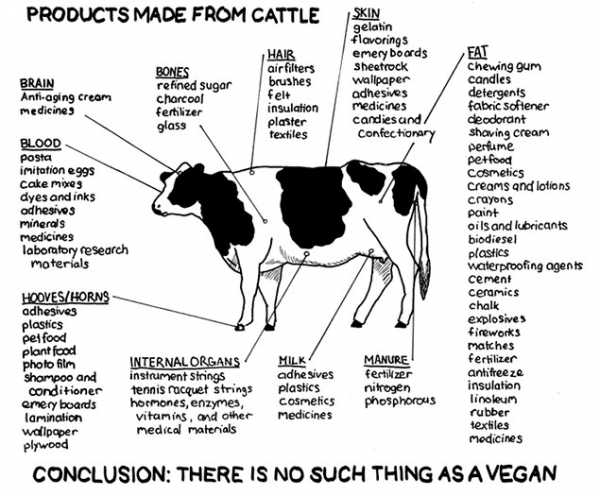

expediting regulations prohibiting ruminant protein in ruminant feeds, boosting longer stand) were rendered and fed to other cattle, and that BSE could make AIDS look like a common cold. The chief scientist for the U.S. National Cattleman’s Beef Association, rather than stressing the risk management actions that had been taken, was left arguing that cows were not vegetarians because they drank milk.

longer stand) were rendered and fed to other cattle, and that BSE could make AIDS look like a common cold. The chief scientist for the U.S. National Cattleman’s Beef Association, rather than stressing the risk management actions that had been taken, was left arguing that cows were not vegetarians because they drank milk. immediately washed, the skin is removed, and within minutes, the workers also remove the hooves, the hide and the head. The carcass is then moved to a giant cooler, where it stays for up to two days. After it’s been inspected and graded, it’s packaged, loaded on trucks and soon ends up in our local restaurants and stores.

immediately washed, the skin is removed, and within minutes, the workers also remove the hooves, the hide and the head. The carcass is then moved to a giant cooler, where it stays for up to two days. After it’s been inspected and graded, it’s packaged, loaded on trucks and soon ends up in our local restaurants and stores. committed to doing it right. And I believe that when animals are handled with dignity and harvested carefully, that’s the natural order of things,’ says Nicole.

committed to doing it right. And I believe that when animals are handled with dignity and harvested carefully, that’s the natural order of things,’ says Nicole.

What’s worse is that sustainably-minded Michael Pollan is stiffing students for $25,000 to come and share his menu planner.

What’s worse is that sustainably-minded Michael Pollan is stiffing students for $25,000 to come and share his menu planner..jpg) But over time, my own knowledge increased, and I realized that several of these exposes were really just literary clichés, citing a few sources here and there, usually to validate a pre-existing ideal.

But over time, my own knowledge increased, and I realized that several of these exposes were really just literary clichés, citing a few sources here and there, usually to validate a pre-existing ideal..jpg) Anyone can be a poser and critic; Frank actually tries to make change.

Anyone can be a poser and critic; Frank actually tries to make change.