Timothy D. Lytton, Associate Dean for Research & Faculty Development and Distinguished University Professor & Professor of Law at Georgia State University College of Law writes in this contributed op-ed that:

The Trump administration on June 21 unveiled an ambitious plan to consolidate federal food safety efforts within the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Currently, 15 agencies throughout the federal government administer 35 different laws related to food safety under the oversight of nine congressional committees.

Currently, 15 agencies throughout the federal government administer 35 different laws related to food safety under the oversight of nine congressional committees.

The administration calls this system “illogical” and “fragmented.”

“While [the USDA’s Food Safety Inspection Service] has regulatory responsibility for the safety of liquid eggs, [the Food and Drug Administration in the Department of Health and Human Services] has regulatory responsibility for the safety of eggs while they are inside of their shells,” the document explains. “FDA regulates cheese pizza, but if there is pepperoni on top, it falls under the jurisdiction of FSIS; FDA regulates closed-faced meat sandwiches, while FSIS regulates open-faced meat sandwiches.”

Concern about this state of affairs has been fueling similar consolidation proposals for decades.

But my research for a forthcoming book on the U.S. food safety system suggests that the Trump administration plan faces a number of challenges that make a major reorganization of federal food safety regulation both impractical and undesirable.

The curious division of labor between the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Food and Drug Administration dates back to the passage of two laws enacted in 1906.

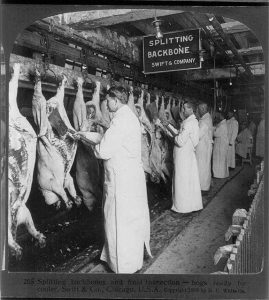

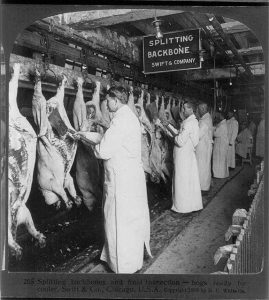

The Meat Inspection Act mandated inspection of all beef carcasses. The Pure Food and Drug Act prohibited the sale of adulterated food in interstate commerce.

Initially, both laws were implemented by officials at the USDA. Its Bureau of Animal Industry placed inspectors trained in veterinary science at every meat plant. Meanwhile, its Bureau of Chemistry employed laboratory scientists to test foods for adulteration.

In 1940, Franklin Roosevelt moved the Bureau of Chemistry, by then renamed the Food and Drug Administration, out of the USDA and into the Federal Security Agency, which later became the Department of Health and Human Services. Today, the FDA is responsible for overseeing the production of most foods other than meat and poultry.

Separately, the Bureau of Animal Industry was renamed the Food Safety Inspection Service, which is still responsible for all meat and poultry inspections.

Concerns about regulatory fragmentation grew as Congress assigned new tasks related to food safety to a variety of other agencies.

Concerns about regulatory fragmentation grew as Congress assigned new tasks related to food safety to a variety of other agencies.

For example, Congress instructed the Federal Trade Commission to regulate food advertising, the Environmental Protection Agency to set pesticide tolerances and the National Marine Fisheries Service to inspect seafood.

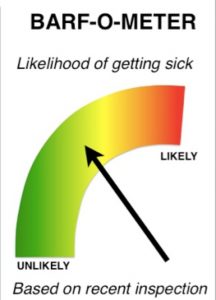

Proponents of putting food safety under the roof of a single agency have argued that the current system causes confusion because different agencies produce inconsistent standards.

They further allege that overlapping jurisdictions create inefficiencies and that inadequate coordination leaves gaps in coverage. They also worry that the involvement of so many different actors diffuses political accountability.

The first high-profile proposal to consolidate federal food safety regulation was made in 1949, during the Truman administration, when a presidential commission recommended transferring food safety oversight to the USDA, just as the Trump administration has.

In 1972, consumer activist Ralph Nader advocated creating a new consumer safety agency to oversee food safety. And a few years later, a Senate committee recommended moving the USDA’s food safety responsibilities to the FDA.

Those are just three examples of more than 20 such proposals from both sides of the political aisle, including one by President Barack Obama in 2015.

None of these consolidation efforts succeeded for the same reasons the current one is unlikely to work now.

First of all, the many congressional committees that currently oversee agencies that regulate food safety are unlikely to support any reorganization that would reduce their power. Congressional oversight affords lawmakers who serve on committees opportunities to help interest groups and constituents in exchange for political support.

Similarly, industry associations are unlikely to support a reorganization that would disrupt their relationships with existing agencies. Consolidation threatens to reduce their access and influence over agency decisions.

In addition to the political obstacles to consolidation, there are practical problems. Merely merging the 5,000 food safety officials in the FDA and the 9,200 officials in the FSIS under the oversight of a single administrator would not eliminate the differences in jurisdiction, powers and expertise responsible for the current bureaucratic fragmentation. Meaningful consolidation would require a complete overhaul of federal food safety laws and regulations, a task of extraordinary legal and political complexity.

Moreover, consolidating food safety efforts in a single agency might create new forms of fragmentation. For example, transferring the FDA Center for Veterinary Medicine’s program for regulating drug residues in beef and poultry to the USDA would separate it from the FDA’s veterinary drug approval program.

And finally, reorganization is costly and would take years for the different agency teams newly working together to develop bonds of trust and cooperation. And these costs would have to be paid upfront, without a clear idea of whether the expected gains will ever pay off.

Consolidation need not be all or nothing.

For example, some have proposed more modest consolidation of inspection services, policy planning and communications that would be less costly and not so difficult.

Nonetheless, Congress has shown little interest in considering any bureaucratic reorganization of federal food safety regulation, even a partial consolidation.

In other words, the Trump administration may have to settle for the less ambitious goal of better interagency coordination, which offers an alternative way to address concerns about duplication and coverage gaps. This more modest approach would not, however, address the persistent problem of fragmentation.

In food safety, as in other regulatory reform arenas, it may turn out that half a loaf is better than none.

So me and Chapman and this student had a chat this morning about how she wants to do more work for us over the summer.

So me and Chapman and this student had a chat this morning about how she wants to do more work for us over the summer.