Several types of mettwurst, manufactured by a South Australian Company, have been recalled after it was discovered the products may be contaminated with harmful bacteria.

Wintulichs, based in Gawler, recalled their Metwurst Garlic 300g, 375g, 500g, 700g, Mettwurst Plain 700g and Mettwurst Pepperoni 375g products.

Wintulichs, based in Gawler, recalled their Metwurst Garlic 300g, 375g, 500g, 700g, Mettwurst Plain 700g and Mettwurst Pepperoni 375g products.

Food Standards Australia New Zealand say the products have been sold at Woolworths, IGA and independent stores across SA.

The recall is due to incorrect pH and water activity levels, which may lead to microbial contamination and could cause illness if consumed.

Customers should return the products to the place of purchase for a full refund.

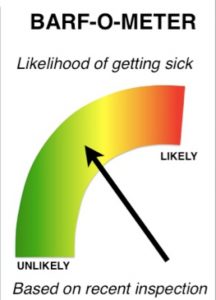

In Australia and around the world, the incidence of reported foodborne illness is on the increase. Regularly cited estimates suggest that Australia is plagued with over two million cases of foodborne illness each year, costing the community in excess of $1 billion annually.

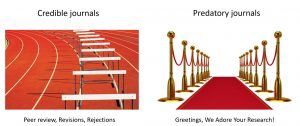

Based on the case studies cited here and a thorough examination of a variety of documents disseminated for public consumption, government and industry in Australia are well aware of the challenges posed by greater public awareness of foodborne illness. They are also well aware of risk communication basics and seem eager to enter the public fray on contentious issues. The primary challenge for government and industry will be to provide evidence that approaches to managing microbial foodborne risks are indeed mitigating and reducing levels of risk; that actions are matching words.

Based on the case studies cited here and a thorough examination of a variety of documents disseminated for public consumption, government and industry in Australia are well aware of the challenges posed by greater public awareness of foodborne illness. They are also well aware of risk communication basics and seem eager to enter the public fray on contentious issues. The primary challenge for government and industry will be to provide evidence that approaches to managing microbial foodborne risks are indeed mitigating and reducing levels of risk; that actions are matching words.

There is a further challenge in impressing upon all producers and processors the importance of food safety vigilance, as well as the need for a comprehensive crisis management plan for critical food safety issues.

On Feb. 1, 1995, the first report of a food poisoning outbreak in Australia involving the death of a child from hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) after eating contaminated mettwurst reached the national press. The next day, the causative organism was identified in news stories as E. coli 0111, a Shiga-toxin E. coli (STEC) which was previously thought to be destroyed by the acidity in fermented sausage products like mettwurst, an uncooked, semi-dry fermented sausage. By Feb. 3, 1995, the child was identified as a four-year-old girl and the number sickened in the outbreak was estimated at 21.

The manager of the company that allegedly produced the contaminated mettwurst had to hire security guards to protect his family home as threats continued to be made on his life, and the social actors began jockeying for position in the public discourse. The company, Garibaldi, blamed a slaughterhouse for providing the contaminated product, while the State’s chief meat hygiene officer insisted that meat inspections and slaughtering techniques in Australian abattoirs were “top class and only getting better.”

On Feb. 4, just three days after the initial, national report, the South Australian state government announced it was implementing new food regulations effective March 1, 1995. The federal government followed suit the next day, announcing intentions to bolster food processing standards and launching a full inquiry. Even the coroner investigating the death of the girl said on Feb. 9 that investigations relating to inquests usually took about three months to complete, but he would start the hearing the next day if possible.

By Feb. 6, 1995, Garibaldi Smallgoods declared bankruptcy. Sales of smallgoods like mettwurst were down anywhere from 50 to 100 per cent according to the National Smallgoods Council.

The outbreak of E. coli O111 and the reverberations fundamentally changed the public discussion of foodborne illness in Australia, much as similar outbreaks of STEC in Japan, the U.K. and the U.S. subsequently altered public perception, regulatory efforts and industry pronouncements in those countries. The pattern of public reporting and response followed a similar pattern of reporting on the medical implications of the illness, attempts to determine causation and finger pointing. Such patterns of reporting are valid; when people are sick and in some cases dying from the food they consume, people want to know why. The results altered both the scientific and public landscapes regarding microbial foodborne illness, and can inform future risk communication and management efforts.

In all, 173 people were stricken by foodborne illness linked to consumption of mettwurst manufactured by Garibaldi smallgoods. Twenty-three people, mainly children, developed HUS, and one died. Although sporadic cases of HUS had been previously reported, this was the first outbreak of this condition recognized in Australia.

Once public attention focused on Garibaldi as the source of the offending foodstuff, the company quickly deflected criticism, blaming an unnamed Victorian-based company of supplying contaminated raw meat, and citing historical precedent as proof of safety. Garibaldi’s administration manager Neville Mead was quoted as saying that he was confident hygiene and processing at the plant were up to standard, adding, “We stand by our processing. We’ve done this process now for 24 years and it’s proved successful.” Such blind faith in tradition, even in the face of changing science-based recommendations, even in the face of tragedy, is often a hallmark of outbreaks of foodborne illness, reflecting the deep cultural and social mythologies that are associated with food.

However, given the uncertainties at the time, a spokesman with the Australian Meat and Livestock Association appropriately rejected such allegations, saying, “I believe it is irresponsible of them (Garibaldi) to make that statement when there is absolutely no evidence of that at all.” Likewise, Victorian Meat Authority chairman John Watson said his officers were investigating Garibaldi’s claims, but that even if the raw meat had come from

Victoria, the supplier may not necessarily be the source of the disease, but rather it could be based in Garibaldi’s processing techniques.

Similarly, when Garibaldi accused the watchdog South Australian Health Commission of dragging its feet with investigations, Health Minister, Dr. Michael Armitage responded by publicly stating that, “They indicated to us that they wanted their lawyers first to be involved before they provided us with information (concerning the mettwurst). It was only (after) earlier this week, under the Food Act, we issued a demand for that information, that we got it. So indeed, I would put it to Garibaldi that the boot is completely on the other foot.”

Likewise, South Australia’s chief meat hygiene officer, Robin Van de Graaff rejected such claims, saying that, “These organisms are part of a large family of bugs that are normal inhabitants of the gut of farm animals … If a tragedy like this occurs it is usually because, and it no doubt is in this case, not because of a small amount of contamination at the point of slaughter but because of the method of handling and processing after that.” The statements of government regulators would be subsequently validated.