In 2012, XL Foods in Alberta sickened 18 people with E. coli O157:H7, led to the largest beef recall in Canadian history, and the plant was subsequently bought by JBS of Brazil.

Following in the tradition of Walkerton’s E. coli O157 outbreak and Maple Leaf’s Listeria outbreak, an independent review panel has concluded the outbreak was caused by mediocrity.

Following in the tradition of Walkerton’s E. coli O157 outbreak and Maple Leaf’s Listeria outbreak, an independent review panel has concluded the outbreak was caused by mediocrity.

The largest beef recall in Canadian history happened because a massive Alberta producer regularly failed to clean its equipment properly, reacted too slowly once it realized it was shipping contaminated meat, and on-site government inspectors failed to notice key problems at the plant.

“It was all preventable,” concludes an independent review of the 2012 XL Foods Inc. beef recall, in which 1,800 products were removed from the Canadian and U.S. markets and 18 consumers became sick.

According to the report, the company did not practice what to do in the event of a major recall, and its staff failed to ensure equipment was regularly and properly cleaned. Canadian Food Inspection Agency workers at the plant failed to notice the problems. These and many other issues persisted four years after the government promised sweeping food-safety reforms in response to the 2008 listeria bacteria contamination at Maple Leaf Foods that took the lives of 23 Canadians and led to serious illness in 57 others who ate tainted meat products.

“It was not that long ago,” the report notes in reference to the 2008 recall. “Canada’s food-safety system – then, as now – is recognized as one of the best in the world. Yet, a mere four years later, Canadians found themselves asking how this could have happened once again.”

No, Canada exists in a bubble, with comfortable fairy tales about the best health care in the world and the safest food in the world.

Any outside observer could look at the available data and say, What ….?

Now, documents obtained by CTV News through an Access to Information request show that in one instance in 2014, E. coli was found in meat exported to the United States from the Brooks, Alta. plant now owned by JBS Food Canada.

U.S. food inspectors detected the tainted meat before it ended up on store shelves.

Unsafe meat was exported in three other instances, documents show, but the exact problem is blanked out in the report.

In one instance, a plant worker didn’t do proper testing for E. coli.

The person responsible for on-site verification of the sampling said she “wasn’t really paying attention.”

For its part, JBS Foods said any problems indicated in the inspections have been resolved.

Some of the reports documents made note of instances where employees were standing in two to three inches of pooling blood, contaminated water, and were splashing product when walking.

Employee hygiene was also a concern. Inspectors found:

- No running water in the women’s and men’s bathroom sinks

- No running water in men’s urinal

- Toilets let unflushed with fecal matter

- No paper towels

In a follow-up statement to CTV News, JBS Food said the company “is meeting all relevant food safety standards.”

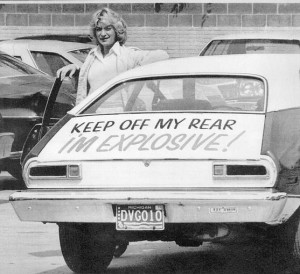

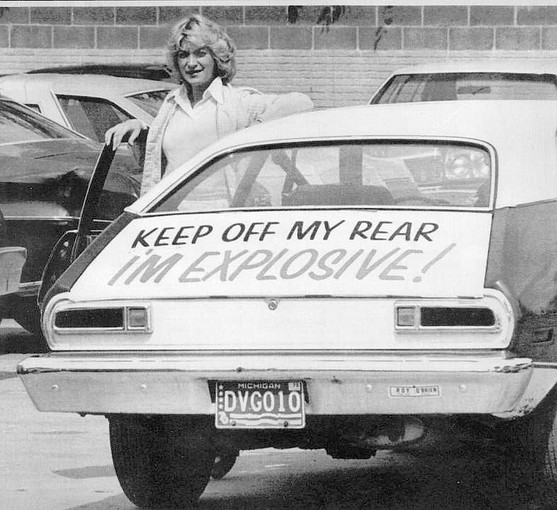

Pinto defense (which was close to a Vega).

create distrust. But, watching the food industry is sometimes like watching the History Channel, a mix of fact, extraterrestrials and the perils of ignoring history.

create distrust. But, watching the food industry is sometimes like watching the History Channel, a mix of fact, extraterrestrials and the perils of ignoring history.