My latest from Texas A&M’s Center for Food Safety:

The UK Food Standards Agency, created in the aftermath of the bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) mess, has sunk to new science-based lows and should be abolished.

The UK Food Standards Agency, created in the aftermath of the bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) mess, has sunk to new science-based lows and should be abolished.

This is not an evidence-based agency, but rather a lapdog for British arrogance.

For years I have criticized the FSA for their endorsement of piping hot as a safe cooking standard.

It is a regulators job to promote policies based on the best scientific evidence, not to appeal to cooking-show inspired public opinion.

For all the taxpayer-supplied millions provided to FSA the best they can do is appeal to the lowest common denominator.

FSA has published details of a proposed new approach to the preparation and service of rare (pink) burgers in food outlets.

The increased popularity of burgers served rare has prompted the FSA to look at how businesses can meet this consumer demand while ensuring public health remains protected.

The FSA’s long-standing advice has been that burgers should be cooked thoroughly until they are steaming hot throughout, the juices run clear and there is no pink meat left inside.

The FSA’s long-standing advice has been that burgers should be cooked thoroughly until they are steaming hot throughout, the juices run clear and there is no pink meat left inside.

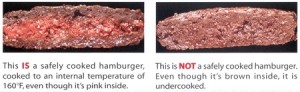

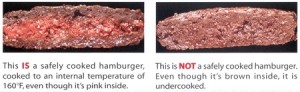

This long-standing advice is stupid, because hamburgers can appear pink yet safely cooked, or brown and undercooked. It has to do with myoglobin in the animal at the age it was slaughtered.

This research was published by Melvin Hunt of Kansas State University in 1998.

But FSA knows better.

They say controls should be in place throughout the supply chain and businesses will need to demonstrate to their local authority officer that the food safety procedures which they implement are appropriate. Examples of some of these controls are:

- sourcing the meat only from establishments which have specific controls in place to minimise the risk of contamination of meat intended to be eaten raw or lightly cooked;

- ensuring that the supplier carries out appropriate testing of raw meat to check that their procedures for minimising contamination are working;

- strict temperature control to prevent growth of any bugs and appropriate preparation and cooking procedures; and,

- providing consumer advice on menus regarding the additional risk from burgers which aren’t thoroughly cooked.

Maybe British inspectors have special bacteria-vision goggles.

Professor Guy Poppy, Chief Scientific Adviser for the Food Standards Agency, said: ‘We are clear that the best way of ensuring burgers are safe to eat is to cook them thoroughly but we acknowledge that some people choose to eat them rare. The proposals we will be discussing with the FSA board in September strike a balance between protecting public health and maintaining consumer choice.’

Not once was a thermometer mentioned. And that’s standard procedure in the U.S., Canada and Australia.

It didn’t take the Daily Mail long to point out that under the proposal, people can eat burgers that are cooked rare and pink in the middle in restaurants, but not at home or on the barbecue.

The move follows pressure from some gourmet burger, pub and restaurant chains who argue that the meat tastes better if it is still pink in the middle.

The move follows pressure from some gourmet burger, pub and restaurant chains who argue that the meat tastes better if it is still pink in the middle.

The proposal, which will have to be approved by the FSA board next month, will also lift the risk of prosecution of food outlets by council environmental health officers.

Officials at the FSA say consumers should be allowed to take an adult decision when eating out whether they want to eat a burger that is pink in the middle.

But it is also arguing that people cannot take this same adult decision when cooking burgers at home.

‘The FSA’s long-standing advice has been that burgers should be cooked thoroughly until they are steaming hot throughout, the juices run clear and there is no pink meat left inside.

These piping hot morons should not be taken seriously by any scientist and should be turfed.

Color sucks. Stick it in and use a thermometer.

Dr. Douglas Powell is a former professor of food safety who shops, cooks and ferments from his home in Brisbane, Australia.

DISCLAIMER: The views and opinions expressed in this blog are those of the original creator and do not necessarily represent that of the Texas A&M Center for Food Safety or Texas A&M University.

Raw egg aioli and mayo is bad enough, and leads to monthly outbreaks of Salmonella across Australia, but to decide that color is a reliable indicator of safety in chicken is stupid beyond belief.

Raw egg aioli and mayo is bad enough, and leads to monthly outbreaks of Salmonella across Australia, but to decide that color is a reliable indicator of safety in chicken is stupid beyond belief. Viewers quickly dubbed the dish “chicken a la salmonella”, with John telling marketing manager Ottilie: “I think you’ve got to know when to stop. It’s all over the place.”

Viewers quickly dubbed the dish “chicken a la salmonella”, with John telling marketing manager Ottilie: “I think you’ve got to know when to stop. It’s all over the place.”

By cooking the livers properly and ensuring good hygiene in the kitchen these episodes can be avoided. However, some celebrity chefs and many recipes advocate only partially cooking chicken liver to ensure that it is pink in the middle.”

By cooking the livers properly and ensuring good hygiene in the kitchen these episodes can be avoided. However, some celebrity chefs and many recipes advocate only partially cooking chicken liver to ensure that it is pink in the middle.”.jpg) brown and an instant-read thermometer inserted into the meaty part of the thigh reads 155 to 165 degrees.”

brown and an instant-read thermometer inserted into the meaty part of the thigh reads 155 to 165 degrees.”