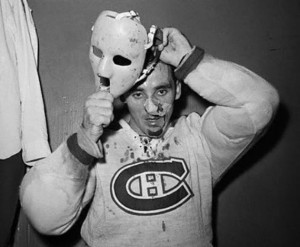

I have a drill I do weekly with the goalies at hockey practice.

I’ll have three of them, each in front of a net, and I tell them, pay attention, you never know where I’m going to shoot the puck (neither do I, but I’m a goalie).

Their job is to know where the puck is and predict where it’s going to be so they can better position themselves. I can look one way but shoot another. The goalie is the last line of defense when others mess up.

Their job is to know where the puck is and predict where it’s going to be so they can better position themselves. I can look one way but shoot another. The goalie is the last line of defense when others mess up.

Much of food safety is, pay attention – especially to the checks that are supposed to reduce risk.

In 2009, the operator of a yakiniku barbecue restaurant chain linked to four deaths and 70 illnesses from E. coli O111 in raw beef in Japan admitted it had not tested raw meat served at its outlets for bacteria, as required by the health ministry.

“We’d never had a positive result [from a bacteria test], not once. So we assumed our meat would always be bacteria-free.”

That’s like telling goalies, unless the shooter is staring at you, the puck will stay out of the net.

Those who study engineering failures –the BP oil well in the Gulf, the space shuttle Challenger, Bhopal – say the same thing: human behavior can mess things up.

In most cases, an attitude prevails that is, “things didn’t go bad yesterday, so the chances are, things won’t go bad today.”

And those in charge begin to ignore the safety systems.

And those in charge begin to ignore the safety systems.

Beginning August 2, 1998, over 80 Americans fell ill, 15 were killed, and at least six women miscarried due to listerosis. On Dec. 19, 1998, the outbreak strain was found in an open package of hot dogs partially consumed by a victim. The manufacturer of the hot dogs, Sara Lee subsidiary Bil Mar Foods, Inc., quickly issued a recall of what would become 35 million pounds of hot dogs and other packaged meats produced at the company’s only plant in Michigan. By Christmas, testing of unopened packages of hot dogs from Bil Mar detected the same genetically unique L. monocytegenes bacteria, and production at the plant was halted.

A decade later, the deaths of two Toronto nursing home residents in the summer of 2008 were attributed to listeriosis infections. These illnesses eventually prompted an August 17, 2008 advisory to consumers by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) and Maple Leaf Foods, Inc. to avoid serving or consuming certain brands of deli meat as the products could be contaminated with L. monocytogenes. When genetic testing determined a match between contaminated meat products and listeriosis patients, all products manufactured at a Toronto Maple Leaf Foods plant were recalled and the facility closed. An investigation by the company determined that organic material trapped deep inside the plant’s meat slicing equipment harbored L. monocytogenes, despite routine sanitization that met specifications of the equipment manufacturer. In total, 57 cases of listeriosis as well as 22 deaths were definitively connected to the consumption of the plant’s contaminated deli meats.

In both Listeria cases, the companies had data that showed an increase in Listeria-positive samples.

In both Listeria cases, the companies had data that showed an increase in Listeria-positive samples.

Pay attention.

One Canadian academic dean-thingy said the 2008 Listeria outbreak was a real eye-opener.

This person should not be in charge of anything to do with microbial food safety.

Food safety culture has been talked about a lot, but it seems so much talk and not so much data.

Food producers should truthfully market their microbial food safety programs, coupled with behavioral-based food safety systems that foster a positive food safety culture from farm-to-fork. The best producers and processors will go far beyond the lowest common denominator of government and should be rewarded in the marketplace.

They should pay attention.

Kellogg’s was taking Salmonella-contaminated peanut paste based on paperwork? Pay attention.

Nestle did.

Australians are so laid back, or so I’m told, they don’t bother to look both ways when driving. Stop signs seem optional.

So I’m always telling my younger and older kids (when they visit) you have to pay attention, because that car will not stop for you.

So I’m always telling my younger and older kids (when they visit) you have to pay attention, because that car will not stop for you.

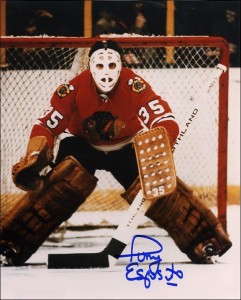

I coach hockey in Australia, where 5-year-olds and 10-year-olds are on the ice at the same time, and I say, pay attention. Because that 10-year-old can wipe you out.

Just like some unexpected bug.

Dr. Douglas Powell is a former professor of food safety who shops, cooks and ferments from his home in Brisbane, Australia.