People in the hospital are invariably immunocompromised. They shouldn’t be fed things like deli meats that may harbor Listeria.

And it shouldn’t be the patient’s responsibility to ask if their doctor or nurse washed their hands.

And it shouldn’t be the patient’s responsibility to ask if their doctor or nurse washed their hands.

A February audit shows more than 40 per cent of health-care workers and support staff at hospitals in the Regina area (that’s in Canada) failed to wash their hands properly.

A follow-up report in June also reveals that 67 per cent of 204 doctors observed didn’t follow regional handwashing rules before patient contact.

Regina Qu’Appelle Health Region (RQHR) requires all staff to wash their hands with soapy water or alcohol-based gels for a minimum of 20 seconds before and after contact with patients. They’re not allowed to wear excessive jewellery on their hands or wrists and can’t have gel nails.

Kateri Singer, the woman in charge of infection prevention for RQHR said the region’s goal is 100 per cent compliance with handwashing rules “because it is the single most important thing we can do as health-care workers.”

CBC’s iTeam has combed through RQHR’s February and June reports and has highlighted some of the least compliant facilities. The following percentages indicate non-compliance rates:

Broadview Union Hospital (February) – 94.8%

Grenfell Health Centre (June) – 77.4%

Regina Lutheran Home (June) – 77.8%

Wolseley Memorial Hospital (June) – 66.7%

Regina General Hospital – Day Surgery (February) – 86.7%

Regina General Hospital – Labour and Birth (June) – 94%

Pasqua Hospital – Day Surgery (February) – 100%

Pasqual Hospital – Short Stay (February) – 95.2%

Pasqua Hospital – Operating Room (February) – 68%

Pasqual Hospital – 3A (June) – 97%

Transparency is a key to change

Singer said though these numbers look bad, she’s committed to disclosure because “the public has the right to know” whether or not their doctor or nurse is keeping their hands clean. And she said patients have the right to hold them to account.

Singer said though these numbers look bad, she’s committed to disclosure because “the public has the right to know” whether or not their doctor or nurse is keeping their hands clean. And she said patients have the right to hold them to account.

RQHR seems to have taken the lead in Saskatchewan when it comes to transparency regarding handwashing practices. Its public reports are far more comprehensive than any other region in the province.

Singer said transparency can be a catalyst to change behavior.

Michael Gardam, director of infection, prevention and control at Toronto’s University Health Network, told CBC Saskatchewan’s Morning Edition host Sheila Coles patients often do not feel they can stand up for themselves.

“I have seen patients get screamed at by health care providers,” Gardam said. “I’ve seen patients be told, ‘Don’t come back to my clinic. How dare you challenge me.'”

.story.jpg)

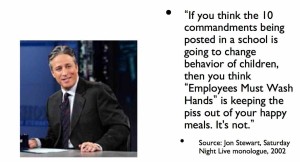

.jpg) patients in hospitals and other clinics in the U.S. every year.

patients in hospitals and other clinics in the U.S. every year. out of your ear, you don’t know where that finger’s been (or where it’s going).

out of your ear, you don’t know where that finger’s been (or where it’s going). The unannounced inspection of the Royal Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital by health watchdog, the Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA), concluded it had "not maintained its level of performance in relation to the delivery of hygiene services" since it was inspected in 2008.

The unannounced inspection of the Royal Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital by health watchdog, the Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA), concluded it had "not maintained its level of performance in relation to the delivery of hygiene services" since it was inspected in 2008.