The coverage of extension associate Katrina Levine’s research on cookbook food safety messages took an unexpected turn yesterday. Gwyneth Paltrow’s ‘people’ weighed in.

By ‘people’ I think it’s the folks who published her cookbooks.

It started with a string of emails from some folks in the UK who saw the NC State press release about the research. After analyzing 1700+ recipes from cookbooks on the New York Times best seller list we found that safe endpoint temperatures only appeared in just over 8% of the instructions.

A few journalists want to know who are the biggest offenders are (quick answer: it’s pretty well everyone we looked at – but not all the time).

One of the books included in our study was Paltrow’s It’s All Good. In a flurry of questions, and without being able to find all the recipes online, I sent one of the enquiring minds a recipe from another book, My Father’s Daughter as an example of what we were looking at, with this note:

“Here’s one from chef Paltrow that does not have a safe endpoint temperature included (165F or 74C).

Heat oven to 400°. Mix butter, garlic salt, paprika, pepper and salt in a bowl. Rinse chicken inside and out; pat dry. Insert fingers between skin and breast to separate the two. Rub seasoned butter over chicken and under skin. Tuck wings underneath bird and tie together with a piece of twine. Tie legs together with another piece of twine. Place chicken on its side in a heavy roasting pan and roast 25 minutes. Turn onto its other side and sprinkle with several tbsp water; roast 25 minutes more. Turn chicken on its back; roast 10 minutes more. Turn on its breast; roast until skin is crispy and chicken is golden brown, 10 minutes more. Remove from pan and let rest, breast side down, 15 minutes, before carving (remove skin).”

The Paltrow folks responded, through the journalist with this:

“The recipe for “Roast Chicken, Rotisserie Style” was published in MY FATHER’S DAUGHTER in April 2011. While it did not have an endpoint temperature included, the directions called for the chicken to be roasted at 400F for 70 minutes, which is ample time to cook a 3-4 pound chicken.

IT’S ALL GOOD, which was published in April 2013, does include endpoint temperatures. “Super-Crispy Roast Chicken” in IT’S ALL GOOD is baked for 1-1/2 hours at 425 degrees and the recipe advises “The chicken thigh should register 165 degrees F on a digital thermometer at the very least (I usually let it get to 180 Degrees F just to be completely sure it’s cooked all the way through the bone).”

So we went back to the data – and yep, we noted that the Super-Crispy Roast Chicken had a safe end point temperature. What they omitted was that the first instruction in the recipe was to wash the chicken; one of the steps that can increase the risk of foodborne illnesses.

There were these other recipes from It’s All Good that don’t have the safe endpoint temperatures (and tell the reader to do non science-based things like touch it, look for clear juices or color to ensure doneness):

- Japanese chicken meatballs

- Turkey meatballs

- Two-pan chicken with harissa, preserved lemons and green (not online)

- Chicken Burgers, Thai-Style

- Tandoori turkey kabobs (not online)

The row (I think that’s the correct colloquial British term) made the front page of the Daily Mail (above, exactly as shown).

As for this comment, ‘the directions called for the chicken to be roasted at 400F for 70 minutes, which is ample time to cook a 3-4 pound chicken.’

Maybe, show me the data. Lots of variables that can impact the final temperature – starting temperature of the chicken, thickness, oven heat calibration.

Isn’t it just easier to tell folks what the safe temperature is and tell them to stick it in?

Food and Wine points out exactly what we found. It’s not just Gwyneth.

But for once, let’s cut Paltrow some slack. Out of the whopping 29 best-selling cookbooks these experts analyzed, only nine percent of them included specific temperature information. She’s in good company. Meanwhile, only 89 — 89! — of the 1,497 recipes included in the study were deemed instructionally safe.

Honestly, none of this seems too egregious, and we almost wish Paltrow didn’t have to deal with the PR headache.

Oh well.

.jpg) my departmental colleagues — we don’t really know what Powell does.

my departmental colleagues — we don’t really know what Powell does. with public stakeholders and enhance their engagement with interested individuals, groups, and subject matter experts.

with public stakeholders and enhance their engagement with interested individuals, groups, and subject matter experts.

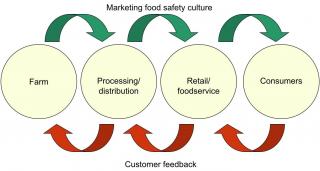

.jpg) regulations and inspections, or their food safety culture, is often overlooked.

regulations and inspections, or their food safety culture, is often overlooked.

(1).jpg) However, it remains a challenge to compel food producers, processors, distributors, retailers, foodservice outlets and home meal preparers to adopt scientifically validated safe food handling behaviors, especially in the absence of an outbreak.

However, it remains a challenge to compel food producers, processors, distributors, retailers, foodservice outlets and home meal preparers to adopt scientifically validated safe food handling behaviors, especially in the absence of an outbreak. • stay up-to-date on emerging food safety issues;

• stay up-to-date on emerging food safety issues;.jpg) encouragement and enforcement to foster a food safety culture; and use technology to be transparent – whether it’s live webcams in the facility or real-time test results on the website – to help restore the shattered trust with the buying public.

encouragement and enforcement to foster a food safety culture; and use technology to be transparent – whether it’s live webcams in the facility or real-time test results on the website – to help restore the shattered trust with the buying public.(1)(1).jpg) demonstrable way. In an organization with a good food safety culture, individuals are expected to enact practices that represent the shared value system and point out where others may fail. By using a variety of tools, consequences and incentives, businesses can demonstrate to their staff and customers that they are aware of current food safety issues, that they can learn from others’ mistakes, and that food safety is important within the organization. The three case studies presented in this paper demonstrate that creating a culture of food safety requires application of the best science with the best management and communication systems, including compelling, rapid, relevant, reliable and repeated food safety messages using multiple media.

demonstrable way. In an organization with a good food safety culture, individuals are expected to enact practices that represent the shared value system and point out where others may fail. By using a variety of tools, consequences and incentives, businesses can demonstrate to their staff and customers that they are aware of current food safety issues, that they can learn from others’ mistakes, and that food safety is important within the organization. The three case studies presented in this paper demonstrate that creating a culture of food safety requires application of the best science with the best management and communication systems, including compelling, rapid, relevant, reliable and repeated food safety messages using multiple media.