With an appeal to the simplistic, Barbara Laino says, “We know processed foods are wrong for us. It has to be wrong for them. If you can feed yourself healthily and your children, then you can feed your pets healthily, too. It really isn’t that hard.”

Laino is talking about the standard recipe she uses to feed her Alaskan malamute, another dog and three cats in her house for around 10 days: grind 40 pounds of pasture-raised chicken necks with another 20 pounds of chicken giblets. To this, she adds five .jpg) pounds of carrots, a whole cabbage and several other fruits, all from the organic fields of Midsummer Farm, Ms. Laino’s farm in Warwick, N.Y. Finally, she blends the mix with herbs and supplements.

pounds of carrots, a whole cabbage and several other fruits, all from the organic fields of Midsummer Farm, Ms. Laino’s farm in Warwick, N.Y. Finally, she blends the mix with herbs and supplements.

She tells the New York Times in a piece of pet food porn that she wants for her pets what she wants for herself: a healthy diet of unprocessed organic foods. And now she teaches others.

Cesar Millan, host of the television show “The Dog Whisperer,” says, “The dog has always been a mirror of the human style of life. Organic has become a new fashion, a new style of living.”

Cesar got the lifestyle bit right, because that is all it is; as for microbiological safety, the cross-contamination risks alone in the food prep sound daunting.

Nancy K. Cook, the vice president at the Pet Food Institute, a trade association for commercial pet food makers, cautions pet owners that it is hard to create a balanced diet at home, since dogs and cats have specific nutritional requirements.

Joseph J. Wakshlag, a clinical nutritionist at the Baker Institute for Animal Health at Cornell University, said that if pets are not fed the correct balance of proteins, fats,  minerals and vitamins, they can experience several health disorders, including anemia, broken bones and loss of teeth from lack of calcium.

minerals and vitamins, they can experience several health disorders, including anemia, broken bones and loss of teeth from lack of calcium.

Korinn Saker, a clinical nutritionist at the College of Veterinary Medicine at North Carolina State University, who treats animals at the school’s teaching hospital, said she was not against people cooking for their pets, but that if it was not done correctly, the consequences could be harmful.

She has seen several dogs with adverse effects from unbalanced homemade pet food diets, including a German shepherd puppy “who was walking on its elbows because it had no strength in its bones,” she said. The dog, it turned out, was not getting enough calcium.

Dr. Saker, asked to analyze the recipe from Ms. Laino’s workshop, found that it was lacking in a number of nutrients recommended by the Association of American Feed Control Officials.

Ms. Laino said she rejects the standards recommended by the feed association, and .jpg) suggested that her recipe might be richer in certain nutrients because the ingredients are organic.

suggested that her recipe might be richer in certain nutrients because the ingredients are organic.

Hucksterism is alive and well for Barbara Laino and the N.Y. Times.

The Whole Story blog of Whole Foods

The Whole Story blog of Whole Foods Why? Is it safer? No. Do the production methods extract less of a toll on the soil? No.

Why? Is it safer? No. Do the production methods extract less of a toll on the soil? No. Christine Bushway, Executive Director of the Organic Trade Association (OTA) says “organic agriculture is the most highly regulated system of agricultural production in the U.S., and the USDA-accredited verification system, especially its recordkeeping and inspection requirements, should be recognized and considered by FDA when drafting rules requiring similar features.”

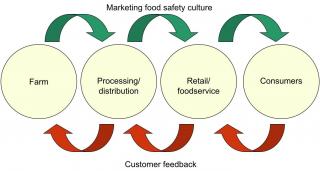

Christine Bushway, Executive Director of the Organic Trade Association (OTA) says “organic agriculture is the most highly regulated system of agricultural production in the U.S., and the USDA-accredited verification system, especially its recordkeeping and inspection requirements, should be recognized and considered by FDA when drafting rules requiring similar features.”.jpg) Increased attention has been focused on fresh fruits and vegetables, especially raw or minimally processed, as a significant source of foodborne illness. Outbreaks have been linked to both conventionally and organically grown produce. This paper outlines the risks associated with fresh produce, common pathways of contamination, and current trends in organic agriculture. The primary objective was to determine whether the Canadian General Standards Board (CGSB) organic standard is consistent with the production of microbiologically safe produce and to examine the potential for the CGSB organic standard to include considerations for microbial food safety. This objective was achieved by examining information gaps between the US Food and Drug Administration on-farm food safety guidelines and the organic standard developed by the CGSB. This examination showed a significant degree of commonality and, in some cases, it was demonstrated that microbial food safety standards are achieved indirectly under organic production. The main difference between the U.S. guidelines and the CGSB standard is the focus on the process rather than the safety of the final product,and the lack of discussion of microbial considerations in the CGSB standard. Specific omissions include worker hygiene and recommendations for safe use of processing and irrigation water. The production of safe food is the responsibility of everyone in the farm-to-fork chain. With established relationships between growers and regulatory infrastructure, the CGSB organic standard would be an ideal vehicle for providing organic growers with information and guidelines on identifying and controlling microbial hazards on their produce.

Increased attention has been focused on fresh fruits and vegetables, especially raw or minimally processed, as a significant source of foodborne illness. Outbreaks have been linked to both conventionally and organically grown produce. This paper outlines the risks associated with fresh produce, common pathways of contamination, and current trends in organic agriculture. The primary objective was to determine whether the Canadian General Standards Board (CGSB) organic standard is consistent with the production of microbiologically safe produce and to examine the potential for the CGSB organic standard to include considerations for microbial food safety. This objective was achieved by examining information gaps between the US Food and Drug Administration on-farm food safety guidelines and the organic standard developed by the CGSB. This examination showed a significant degree of commonality and, in some cases, it was demonstrated that microbial food safety standards are achieved indirectly under organic production. The main difference between the U.S. guidelines and the CGSB standard is the focus on the process rather than the safety of the final product,and the lack of discussion of microbial considerations in the CGSB standard. Specific omissions include worker hygiene and recommendations for safe use of processing and irrigation water. The production of safe food is the responsibility of everyone in the farm-to-fork chain. With established relationships between growers and regulatory infrastructure, the CGSB organic standard would be an ideal vehicle for providing organic growers with information and guidelines on identifying and controlling microbial hazards on their produce. Powell, an associate professor of food safety, is the co-author of "Coverage of organic agriculture in North American newspapers: Media — linking food safety, the environment, human health and organic agriculture," just published in the British Food Journal.

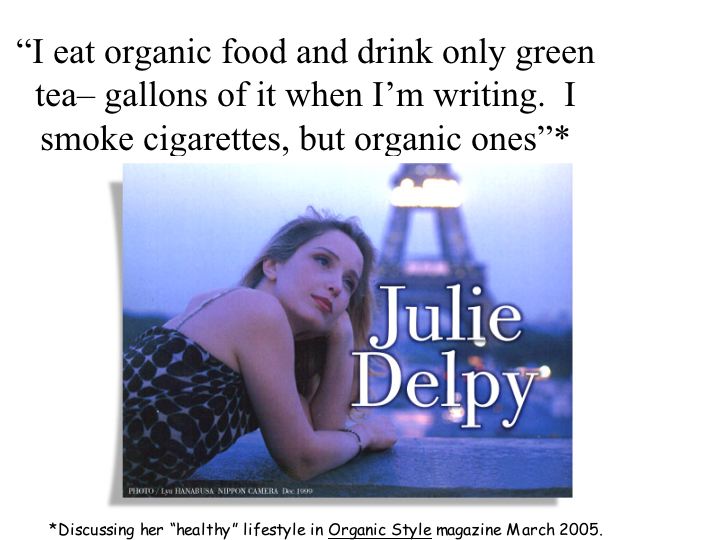

Powell, an associate professor of food safety, is the co-author of "Coverage of organic agriculture in North American newspapers: Media — linking food safety, the environment, human health and organic agriculture," just published in the British Food Journal. "Food safety was the least important in the media discussion of organic agriculture," Powell said. "The finding that 50 percent of food safety-themed statements in news articles were positive with respect to organic agriculture, while 81 percent of health-themed statements and 90 percent of environment-themed statements were positive toward organic food, indicates an uncritical press."

"Food safety was the least important in the media discussion of organic agriculture," Powell said. "The finding that 50 percent of food safety-themed statements in news articles were positive with respect to organic agriculture, while 81 percent of health-themed statements and 90 percent of environment-themed statements were positive toward organic food, indicates an uncritical press." There wasn’t a lot of data.

There wasn’t a lot of data. data from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and found that many products such as maple syrup and eggs did not meet safety standards. The article stated that, “to avoid health problems, Mary McGrath, the group’s director of research, suggested consumers consider purchasing organic or ecologically grown produce” (Sokoloff, 2002). Such unsubstantiated comments have become endemic in media coverage of all things organic.

data from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and found that many products such as maple syrup and eggs did not meet safety standards. The article stated that, “to avoid health problems, Mary McGrath, the group’s director of research, suggested consumers consider purchasing organic or ecologically grown produce” (Sokoloff, 2002). Such unsubstantiated comments have become endemic in media coverage of all things organic. best producers use techniques – regardless of political ideology – that fit best in their production system in their geographic location.

best producers use techniques – regardless of political ideology – that fit best in their production system in their geographic location. first time I lived close to a downtown market (right, San Francisco market, 2009). For my third year as an undergraduate university student — what Americans would call my junior year — I had a room that used to be the garage in a semi-detached sorta house and was exceedingly cold in the winter. I lived with a mom and her 8-year-old son, and got free rent in exchange for a couple of hours of child care in the early evenings.

first time I lived close to a downtown market (right, San Francisco market, 2009). For my third year as an undergraduate university student — what Americans would call my junior year — I had a room that used to be the garage in a semi-detached sorta house and was exceedingly cold in the winter. I lived with a mom and her 8-year-old son, and got free rent in exchange for a couple of hours of child care in the early evenings.