Whenever a group says the public needs to be educated about food safety, biotechnology, trans fats, organics or anything else, that group has utterly failed to present a compelling case for their cause.

I cringe, and remember a Lewis Lapham column I read in Harper’s magazine in the mid-1980s about how individuals can choose to educate themselves about all sorts of interesting things, but the idea of educating someone is doomed to failure. Oh, and it’s sorta arrogant to state that others need to be educated; to imply that if only you understood the world as I understand the world, we would agree and dissent would be minimized.

.jpg) What nonsense.

What nonsense.

Yet millions are wasted weekly on such campaigns.

Industry, government, academia, activists, they all resort to the same language when it comes to providing information: them folks need to get edumacated.

In the past year:

• the American Ag & Energy Council said it believed in promoting all the good the industry does through education;

• Shell Malaysia chairman Datuk Saw Choo Boon told Malaysians efforts should concentrate on educating the public to become twice as efficient in energy use by 2050;

• an industry type said food irradiation is safe, but its adoption by the industry would require a massive consumer education campaign;

• the U.S. beef checkoff supported the efforts of federal agencies in promoting beef safety through educational activities;

• the Canadian Partnership for Consumer Food Safety Education has it right in their horribly bureaucratic name;

• as does the U.S. Partnership for Food Safety Education, dedicated to improving public health through research-based, actionable consumer food safety education; and,

• retailers are joining the group effort to educate millions of consumers about food safety.

A long time ago, I wrote,

There is a dearth of scientific studies applying proven risk communication concepts to issues of microbial food safety. There is, however, an abundance of academic, industrial and government pronouncements on how to improve communications activities related to food safety, based on anecdotal evidence and almost always citing the need for “educated consumers” or “a better-educated public.”

Such proposals invoke a one-way, authoritarian model of communication that is characteristic of scientists and engineers in general. Further, exactly how this mythical consumer will become better educated remains a mystery. What is known is that the traditional approach of scientists clearly explaining the facts is “naive—and probably a recipe for failure. … Effective communication

“Too often, risk communicators are more concerned with educating the public, rather than first listening to them and then developing communication policies.”

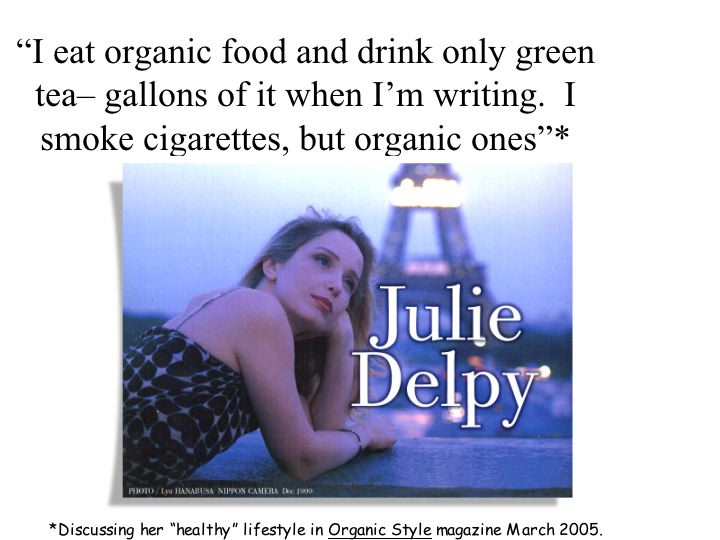

So it’s not surprising that the organic industry is also lacking in imagination and has launched a national consumer education and marketing campaign.

The Organic Agriculture and Products Education Institute (Organic Institute) has launched "Organic. It’s worth it."

The Organic Agriculture and Products Education Institute (Organic Institute) has launched "Organic. It’s worth it."

"The mission of this campaign is to answer consumer questions about organic with the clear message that organic is worth it in every way from health care and economics to farming and the environment. It will increase consumer trust, knowledge and purchase of organic products," said Christine Bushway, president of the Organic Institute and executive director of the Organic Trade Association (OTA), the sponsor of the campaign.

Designed to be of service to families with young children at home, the campaign especially seeks to reach new mothers, the primary gateways to organic, according to OTA Marketing Director Laura Batcha, who developed the campaign with Haberman, the Minneapolis brand public relations firm, on behalf of the Organic Institute.

"Helping mothers make the connection between the personal health of their families and the health of the environment is key to this education and marketing initiative," explained Batcha. "It gives them the rationale they need to make the organic purchase."

Of course, as the N.Y. Times points out this morning, organic has nothing to do with food safety. It’s a production standard, and a porous one at that. But consumers believe that organic is healthier and safer, according to surveys. The organic industry will never come out and say it’s safer, but they hint at it through marketing (see above).

So it’s a shock to some that Peanut Corporation of America plants in Virginia and Texas were certified organic, revealing the same Ponzi scheme of inspection and auditing that failed to catch Salmonella problems in the plants.

So it’s a shock to some that Peanut Corporation of America plants in Virginia and Texas were certified organic, revealing the same Ponzi scheme of inspection and auditing that failed to catch Salmonella problems in the plants.

As the Times states,

Although the rules governing organic food require health inspections and pest-management plans, organic certification technically has nothing to do with food safety. …

A private certifier took nearly seven months to recommend that the U.S.D.A. revoke the organic certification of the peanut company’s Georgia plant, and then did so only after the company was in the thick of a massive food recall. So far, nearly 3,000 products have been recalled, including popular organic items from companies like Clif Bar and Cascadian Farm. Nine people have died and almost 700 have become ill.

The private certifier, the Organic Crop Improvement Association, sent a notice in July to the peanut company saying it was no longer complying with organic standards, said Jeff See, the association’s executive director. He would not say why his company wanted to pull the certification.

A second notice was sent in September, but it wasn’t until Feb. 4 that the certifier finally told the agriculture department that the company should lose its ability to use the organic label.

A second notice was sent in September, but it wasn’t until Feb. 4 that the certifier finally told the agriculture department that the company should lose its ability to use the organic label.

To emphasize that reporting basic health violations is part of an organic inspector’s job, Barbara C. Robinson, acting director of the agriculture department’s National Organic Program, last week issued a directive to the 96 organizations that perform foreign and domestic organic inspections that they are obligated to look beyond pesticide levels and crop management techniques.

Potential health violations like rats — which were reported by federal inspectors and former workers at the Texas and Georgia plants — must be reported to the proper health and safety agency, the directive said.

Wow. Organic inspectors have to be told by the feds that rats may pose a health risk and should be reported.

Arthur Harvey, a Maine blueberry farmer who does organic inspections, said agents have an incentive to approve companies that are paying them.

“Certifiers have a considerable financial interest in keeping their clients going,” he said.

OMG. Organic, like other food systems, is about making money.

Is there a better way? Yes, market microbial food safety and hold producers and processors – conventional, organic or otherwise – to a standard of producing food that doesn’t make people barf. That’s something shoppers will support, instead of being told they have to become better educated about someone else’s limited perspective.

I don’t think it’s sustainable to drive 11,000 miles to brag about it. I just like my garden. And I have an excellent crop of blackberries and raspberries coming in.

.jpg) As the Times story put it,

As the Times story put it,.jpg) What can be said is that local/small/organic is a lifestyle choice. And like any lifestyle choice, go for it but play safe. Try not to make people barf and even embrace evidence-based microbiologically safe food. Sales will probably increase.

What can be said is that local/small/organic is a lifestyle choice. And like any lifestyle choice, go for it but play safe. Try not to make people barf and even embrace evidence-based microbiologically safe food. Sales will probably increase..jpg) The best and most dangerous mythology in the story is this:

The best and most dangerous mythology in the story is this:(1).jpg) “Health professionals are adamant that all fresh produce should be cleaned to remove potential pathogens. … Even produce sold as ‘pre-washed’ needs to be washed. … As organic produce has been annexed by big commercial enterprises, it is increasingly scrubbed up in huge pack houses that bring together produce from large numbers of farms for a good dousing.”

“Health professionals are adamant that all fresh produce should be cleaned to remove potential pathogens. … Even produce sold as ‘pre-washed’ needs to be washed. … As organic produce has been annexed by big commercial enterprises, it is increasingly scrubbed up in huge pack houses that bring together produce from large numbers of farms for a good dousing.” That’s why they use pictures like the one, right, to portray the organic industry. I look at the picture and wonder where those hands have been and what kind of poop is being spread on that fresh produce.

That’s why they use pictures like the one, right, to portray the organic industry. I look at the picture and wonder where those hands have been and what kind of poop is being spread on that fresh produce..jpg) What nonsense.

What nonsense. The Organic Agriculture and Products Education Institute (Organic Institute) has launched "

The Organic Agriculture and Products Education Institute (Organic Institute) has launched " So it’s a shock to some that Peanut Corporation of America plants in Virginia and Texas were certified organic, revealing the same Ponzi scheme of inspection and auditing that failed to catch Salmonella problems in the plants.

So it’s a shock to some that Peanut Corporation of America plants in Virginia and Texas were certified organic, revealing the same Ponzi scheme of inspection and auditing that failed to catch Salmonella problems in the plants. A second notice was sent in September, but it wasn’t until Feb. 4 that the certifier finally told the agriculture department that the company should lose its ability to use the organic label.

A second notice was sent in September, but it wasn’t until Feb. 4 that the certifier finally told the agriculture department that the company should lose its ability to use the organic label. All lots of Farmer John’s Herbs brand Organic Basil Leaf, sold in 6 gram packages, bearing UPC 7 73353 50002 1 are affected by this recall.

All lots of Farmer John’s Herbs brand Organic Basil Leaf, sold in 6 gram packages, bearing UPC 7 73353 50002 1 are affected by this recall. In a

In a

The Norwegian Food Safety Authority

The Norwegian Food Safety Authority But we’re all experts cause we all eat.

But we’re all experts cause we all eat.