On June 12, 1996, Dr. Richard Schabas, chief medical officer of Ontario (that’s a province in Canada), issued a public health advisory on the presumed link between consumption of California strawberries and an outbreak of diarrheal illness among some 40 people in the Metro Toronto area. The announcement followed a similar statement from the Department of Health and Human Services in Houston, Texas, which was investigating a cluster of 18 cases of cyclospora illness among oil executives.

Turns out it was Guatemalan raspberries, and no one was happy.

The initial, and subsequent, links between cyclospora and strawberries or raspberries in 1996 was based on epidemiology, a statistical association between consumption of a particular food and the onset of disease. The Toronto outbreak was first identified because some 35 guests .jpg) attending a May 11, 1996 wedding reception developed the same severe, intestinal illness, seven to 10 days after the wedding, and subsequently tested positive for cyclospora. Based on interviews with those stricken, health authorities in Toronto and Texas concluded that California strawberries were the most likely source. However, attempts to remember exactly what one ate two weeks earlier is an extremely difficult task; and larger foods, like strawberries, are recalled more frequently than smaller foods, like raspberries.

attending a May 11, 1996 wedding reception developed the same severe, intestinal illness, seven to 10 days after the wedding, and subsequently tested positive for cyclospora. Based on interviews with those stricken, health authorities in Toronto and Texas concluded that California strawberries were the most likely source. However, attempts to remember exactly what one ate two weeks earlier is an extremely difficult task; and larger foods, like strawberries, are recalled more frequently than smaller foods, like raspberries.

By July 18, 1996, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control declared that raspberries from Guatemala — which had been sprayed with pesticides mixed with water that could have been contaminated with sewage containing cyclospora — were the likely source of the cyclospora outbreak, which ultimately sickened about 1,000 people across North America. Guatemalan health authorities and producers vigorously refuted the charges. The California Strawberry Commission estimated it lost $15-20 million in reduced strawberry sales.

The California strawberry growers decided the best way to minimize the effects of an outbreak – real or alleged – was to make sure all their growers knew some food safety basics and there was some verification mechanism. The next time someone said, “I got sick and it was your strawberries,” the growers could at least say, “We don’t think it was us, and here’s everything we do to produce the safest product we can.”

That was essentially the prelude for FDA publishing its 1998 Guidance for Industry: Guide to Minimize Microbial Food Safety Hazards for Fresh Fruits and Vegetables. We had already started down the same path, and took those guidelines, as well as others, and created an on-farm food safety program for all 220 growers producing tomatoes and cucumbers under the Ontario Greenhouse Vegetable Growers banner. And set up a credible verification system.

In Aug. 2011, Oregon health officials confirmed that deer droppings caused an E. coli O157:H7 outbreak traced to strawberries that sickened 14 people and killed one. William Keene, senior  epidemiologist with Oregon Public Health, said the outbreak strain turned up in samples from fields in three separate locations.

epidemiologist with Oregon Public Health, said the outbreak strain turned up in samples from fields in three separate locations.

So, in the same way spinach, lettuce and tomato growers have reinvented their food safety pasts, commissions representing berry growers in Oregon, Washington and California have banded together to promote good food safety practices.

The efforts begin this spring with education and training of growers and farm workers on proper handling of fresh fruit, according to a news release.

The best producers or manufacturers can do is diligently manage and mitigate risks and be able to prove such diligence in the court of public opinion; and they’ll do it before the next outbreak.

Jeff also was a stalwart for on-farm food safety for fresh produce, long before it was fashionable.

Jeff also was a stalwart for on-farm food safety for fresh produce, long before it was fashionable.

.jpg) as good as its worst grower.

as good as its worst grower..jpg) attending a May 11, 1996 wedding reception developed the same severe, intestinal illness, seven to 10 days after the wedding, and subsequently tested positive for cyclospora. Based on interviews with those stricken, health authorities in Toronto and Texas concluded that California strawberries were the most likely source. However, attempts to remember exactly what one ate two weeks earlier is an extremely difficult task; and larger foods, like strawberries, are recalled more frequently than smaller foods, like raspberries.

attending a May 11, 1996 wedding reception developed the same severe, intestinal illness, seven to 10 days after the wedding, and subsequently tested positive for cyclospora. Based on interviews with those stricken, health authorities in Toronto and Texas concluded that California strawberries were the most likely source. However, attempts to remember exactly what one ate two weeks earlier is an extremely difficult task; and larger foods, like strawberries, are recalled more frequently than smaller foods, like raspberries. epidemiologist with Oregon Public Health, said the outbreak strain turned up in samples from fields in three separate locations.

epidemiologist with Oregon Public Health, said the outbreak strain turned up in samples from fields in three separate locations. pre-farm gate stage. A more comprehensive and integrated approach to risk management is arguably needed. A call for HACCP on the farm or farm food safety management system may be warranted in future if fresh produce outbreaks continue to rise. However, further research is needed to establish the guidelines of HACCP adoption at the farm level. At present, the rigorous adoption of GAP as a pre-requisite and the practice of HACCP-based plans is a good indicator of the importance of pre-harvest safety.

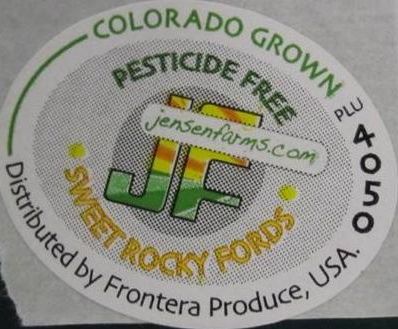

pre-farm gate stage. A more comprehensive and integrated approach to risk management is arguably needed. A call for HACCP on the farm or farm food safety management system may be warranted in future if fresh produce outbreaks continue to rise. However, further research is needed to establish the guidelines of HACCP adoption at the farm level. At present, the rigorous adoption of GAP as a pre-requisite and the practice of HACCP-based plans is a good indicator of the importance of pre-harvest safety..jpg) departments and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. But it had no problem fingering Jensen Farms? Maybe because the Food and Drug Administration named Jensen Farms on Sept. 14 it was open season after that. Maybe CDC was trying to protect other cantaloupe growers. Maybe they’d like to protect other Romaine lettuce growers? Is there a written policy on when to finger a farm? Consistency in communications helps build trust.)

departments and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. But it had no problem fingering Jensen Farms? Maybe because the Food and Drug Administration named Jensen Farms on Sept. 14 it was open season after that. Maybe CDC was trying to protect other cantaloupe growers. Maybe they’d like to protect other Romaine lettuce growers? Is there a written policy on when to finger a farm? Consistency in communications helps build trust.).jpg) sickened at least 123 people and killed 25 in the deadliest outbreak in a quarter-century.

sickened at least 123 people and killed 25 in the deadliest outbreak in a quarter-century.

.jpg) Gladwell would call a

Gladwell would call a .jpg) turned around. Our future depends on it.”

turned around. Our future depends on it.” in 2008 – 24 dead.

in 2008 – 24 dead.