Friend of the barfblog, Michéle Samarya-Timm, with the Somerset County Department of Health (Jersey, represent), writes:

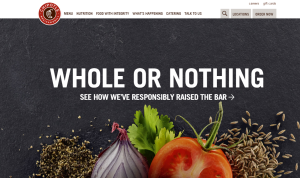

With 39 confirmed E. coli O26 illnesses linked to Chipotle, the restaurant has information on its homepage (paradoxically under a banner of “See how we’ve responsibly raised the bar”). However, Chipotle is verbally minimizing this outbreak, as they choose to call it a “restaurant closure update.”

With 39 confirmed E. coli O26 illnesses linked to Chipotle, the restaurant has information on its homepage (paradoxically under a banner of “See how we’ve responsibly raised the bar”). However, Chipotle is verbally minimizing this outbreak, as they choose to call it a “restaurant closure update.”

The words “outbreak,” “illness” and similar are not used. Chipotle prefers to call it a “situation” and an “issue” (I sense attorneys).

The best folks in risk communication have regularly counseled that corporations experiencing a crisis should communicate regularly with their customers, and not minimize an issue. Considering their previous experiences with Salmonella and Norovirus, Chipotle is still fairly inadequate in this area.

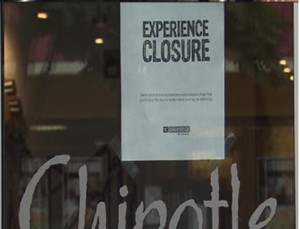

With this in mind, the signs on the doors of their closed stores: “FYI”, “Outage”, “Don’t Panic” and “Experience Closure” sound more like an admonishment to their corporate administration, then they do words of acknowledgement and updates to loyal fans.

At least they have an empathy statement, “We offer our deepest sympathies to those who have been affected by this situation,” but I’m not feeling it.

The most glaring aspect of failing to reach out to those who are loyal to their burritos: Chipotle’s Twitter & Facebook feeds are silent on the issue. For a company with 715,000 followers, and 407,000 marketing tweets, that’s a huge omission.

The most glaring aspect of failing to reach out to those who are loyal to their burritos: Chipotle’s Twitter & Facebook feeds are silent on the issue. For a company with 715,000 followers, and 407,000 marketing tweets, that’s a huge omission.

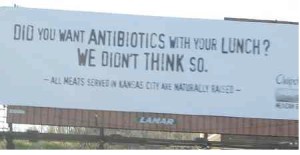

In the absence of corporate messaging, people will make it up. Too bad Chipotle isn’t spending as much effort talking to their customers during this outbreak, as they do reaching out with their slick marketing campaigns.

When the company finally decides to jump back on the social media platform, they may have a hard time overcoming the current circulating meme: You can’t spell Chipotle without E. coli.

.jpg) with O157 should be excluded until at least two consecutive stool samples are negative. Because limited data on O26 are available for O26 infection, no consensus exists on whether similar exclusion should occur.”

with O157 should be excluded until at least two consecutive stool samples are negative. Because limited data on O26 are available for O26 infection, no consensus exists on whether similar exclusion should occur.”.jpeg) the Carrefour Discount brand in Carrefour, Carrefour Market, Carrefour City, Carrefour Contact and Carrefour Montagne stores.

the Carrefour Discount brand in Carrefour, Carrefour Market, Carrefour City, Carrefour Contact and Carrefour Montagne stores. Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) announced today.

Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) announced today.  of an E. coli O26 cluster of illnesses. In conjunction with the Maine Department of Health and Human Services, Maine Department of Agriculture, Food and Rural Resources, the New York State Department of Health, and New York State Department of Agriculture & Markets, two (2) case-patients have been identified in Maine, as well as one (1) case-patient in New York with a rare, indistinguishable PFGE pattern as determined by PFGE subtyping in PulseNet. PulseNet is a national network of public health and food regulatory agency laboratories coordinated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Illness onset dates range from June 24, 2010, through July 16, 2010.

of an E. coli O26 cluster of illnesses. In conjunction with the Maine Department of Health and Human Services, Maine Department of Agriculture, Food and Rural Resources, the New York State Department of Health, and New York State Department of Agriculture & Markets, two (2) case-patients have been identified in Maine, as well as one (1) case-patient in New York with a rare, indistinguishable PFGE pattern as determined by PFGE subtyping in PulseNet. PulseNet is a national network of public health and food regulatory agency laboratories coordinated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Illness onset dates range from June 24, 2010, through July 16, 2010.