This would be a stirring endorsement for the Yosemite Sam mudflap industry if they existed for bikes.

But mudguards are readily available and are being touted by Norwegian and Swedish researchers as a way to reduce the risk of gastroenteritis related to bicycle races over courses  with animal feces and mud.

with animal feces and mud.

The researchers write that Birkebeinerrittet is one of the world’s largest mountain bike races, taking place every year in the mountains in the southeast of Norway. The track is 95 km and around 19,000 participants are expected each year, divided into two races on consecutive days.

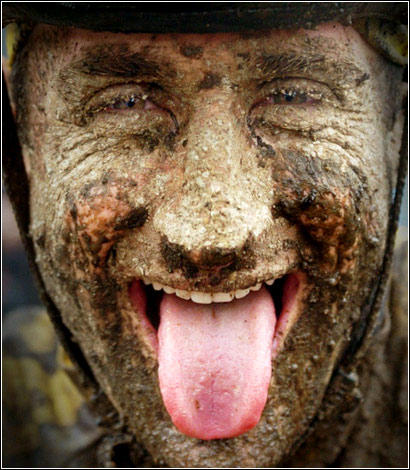

The Birkebeinerrittet track crosses an area where many grazing animals are present. Feces from grazing animals can contain enteropathogens and in wet and muddy conditions, mud splashes to the face during cycling may cause infection.

In 2009, the race took place under severe weather conditions, with heavy rainfall during the previous days. That year, an outbreak of gastrointestinal illness affected an estimated 3,800 participants, resulting in one of the largest diarrheal outbreaks in Norway, with significant media coverage and a heavy socioeconomic toll (more than 2500 days of absence from work). A retrospective

cohort study using web-based questionnaires was performed after the race in order to identify any potential common sources. No single food or drink item was identified as the source; however, mud splashes to the face were associated with gastrointestinal illness.

The study also showed that spitting out the first sip when drinking from a bottle or ‘camelbak’ and using mudguards had some protective effect.

Based on the findings from the 2009 study, the organizers recommended that the participants use mudguards and spit out the first sip of water from drinking bottles during the race in 2010. They also implemented environmental control measures, by draining parts of the track and  spreading gravel in the sareas more prone to get muddy, and asking sheepowners to gather their animals earlier than the previous year, so fewer animals were close to the tracks.

spreading gravel in the sareas more prone to get muddy, and asking sheepowners to gather their animals earlier than the previous year, so fewer animals were close to the tracks.

In 2010 around 19,000 people registered to take part in the races that took place on 27–28 August. Although slightly colder, weather conditions were similar to the previous year. The average temperature was 13.1 C in 2009 and 10.1 C in 2010. Rainfall during the 5 days preceding the races was 43.7 mm in 2009 and 36.6 mm in 2010.

A retrospective cohort study using web-based questionnaires was conducted to measure the use of preventive measures and to assess risk factors associated with gastrointestinal illness. A 69% response rate was achieved and 11,721 records analyzed, with 572 (attack rate 4.9%) matching the case definition, i.e. participants reporting diarrhea within 10 days of race. There was a clear increase in the use of mudguards (96.7% reported access to/receiving information on preventive measures) and a significant decrease in gastrointestinal illness. This may indicate that the measures have been effective and should be considered, both in terms of environmental control measures as well as individual measures.

The complete abstract and paper are available from Epidemiology and Infection at http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=8577676

research evaluating measures on farms and in slaughterhouses to reduce levels of dangerous E. coli.

research evaluating measures on farms and in slaughterhouses to reduce levels of dangerous E. coli..jpg) water in the shower was of a good microbiological, chemical and physical quality. Immediately after pasteurization, the meat was rather pale, but it regained its normal colour after being cooled for 24 hours.

water in the shower was of a good microbiological, chemical and physical quality. Immediately after pasteurization, the meat was rather pale, but it regained its normal colour after being cooled for 24 hours..jpg) The Brattås nursery in Nøtterøy, Vestfold, where the child attends has been asked to tighten up its hygiene policy.

The Brattås nursery in Nøtterøy, Vestfold, where the child attends has been asked to tighten up its hygiene policy..png) product has been withdrawn from the market. No further cases have been reported since 25 October.

product has been withdrawn from the market. No further cases have been reported since 25 October..jpg) further nine lettuce mixes from the market. The Norwegian Food Safety Authority recommends that consumers should not eat these lettuce mixes. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health is continuing the investigation in co-operation with the Food Safety Authority and Veterinary Institute.

further nine lettuce mixes from the market. The Norwegian Food Safety Authority recommends that consumers should not eat these lettuce mixes. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health is continuing the investigation in co-operation with the Food Safety Authority and Veterinary Institute.  which can also give acute kidney failure and change blood chemistry.

which can also give acute kidney failure and change blood chemistry. An outbreak investigation was initiated on 27 May by interviewing the four confirmed cases using a trawling questionnaire. On the same day the NFSA inspectors visited the two households where suspected cases were reported and found an unopened package of sugar peas imported from Kenya in one household, and the packing of the same brand of sugar peas in the other. The sugar peas were bought in the same shop. Based on this suspicion, it was decided to focus the interviews on consumption of fresh vegetables and lettuce.

An outbreak investigation was initiated on 27 May by interviewing the four confirmed cases using a trawling questionnaire. On the same day the NFSA inspectors visited the two households where suspected cases were reported and found an unopened package of sugar peas imported from Kenya in one household, and the packing of the same brand of sugar peas in the other. The sugar peas were bought in the same shop. Based on this suspicion, it was decided to focus the interviews on consumption of fresh vegetables and lettuce..jpg)

“Parents in seven families provided their credit card information and a list of supermarkets where they had shopped. The two supermarket chains that the parents had used most often agreed to help with the investigation. The stores searched their central computers for the precise amount paid and the date and the location of the shop.

“Parents in seven families provided their credit card information and a list of supermarkets where they had shopped. The two supermarket chains that the parents had used most often agreed to help with the investigation. The stores searched their central computers for the precise amount paid and the date and the location of the shop. The Norwegian Food Safety Authority

The Norwegian Food Safety Authority