Every couple of weeks Schaffner and I fire up our old time voice recorder machines (a combination of Skype and a recording app) and talk nerdy to each other about food safety stuff.

And what we’re watching on Netflix. Or Acorn.

And other stuff.

Last week we recorded and posted our 100th episode.

According to the New York Times coverage of a Nature paper, maybe we’re doing more than providing each other with a rant outlet.

We’re creating narratives that fire the brain up, and engage the audience to layer the experience.

Listening to music may make the daily commute tolerable, but streaming a story through the headphones can make it disappear. You were home; now you’re at your desk: What happened?

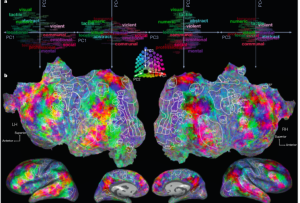

Storytelling happened, and now scientists have mapped the experience of listening to podcasts, specifically “The Moth Radio Hour,” using a scanner to track brain activity. Widely dispersed sensory, emotional and memory networks were humming, across both hemispheres of the brain; no story was “contained” in any one part of the brain, as some textbooks have suggested.

Using novel computational methods, the group broke down the stories into units of meaning: social elements, for example, like friends and parties, as well as locations and emotions . They found that these concepts fell into 12 categories that tended to cause activation in the same parts of people’s brains at the same points throughout the stories.

They then retested that model by seeing how it predicted M.R.I. activity while the volunteers listened to another Moth story. Would related words like mother and father, or times, dates and numbers trigger the same parts of people’s brains? The answer was yes.

And so it goes, for each word and concept as it is added to the narrative flow, as the brain adds and alters layers of networks: A living internal reality takes over the brain. That kaleidoscope of activation certainly feels intuitively right to anyone who’s been utterly lost listening to a good yarn. It also helps explain the proliferation of ear-budded zombies walking the streets, riding buses and subways, fixing the world with their blank stares.

Abstract of the original paper is below:

Natural speech reveals the semantic maps that tile human cerebral cortex

28.apr.16

Nature

Page 532, 453–458

Alexander G. Huth, Wendy A. de Heer, Thomas L. Griffiths, Frédéric E. Theunissen & Jack L. Gallant

The meaning of language is represented in regions of the cerebral cortex collectively known as the ‘semantic system’. However, little of the semantic system has been mapped comprehensively, and the semantic selectivity of most regions is unknown. Here we systematically map semantic selectivity across the cortex using voxel-wise modelling of functional MRI (fMRI) data collected while subjects listened to hours of narrative stories. We show that the semantic system is organized into intricate patterns that seem to be consistent across individuals. We then use a novel generative model to create a detailed semantic atlas. Our results suggest that most areas within the semantic system represent information about specific semantic domains, or groups of related concepts, and our atlas shows which domains are represented in each area. This study demonstrates that data-driven methods—commonplace in studies of human neuroanatomy and functional connectivity—provide a powerful and efficient means for mapping functional representations in the brain.

.jpg)