Chapman’s right when he says I probably didn’t notice him the first year he worked in my lab: it was big, and I had people supervising people.

But he stuck with it, ended up coaching girls hockey with me, bailed me out of jail, published lots of cool research, and now he’s his own prof at North Carolina State.

But he stuck with it, ended up coaching girls hockey with me, bailed me out of jail, published lots of cool research, and now he’s his own prof at North Carolina State.

And he gets to make his own mistakes.

The recent work he and graduate student Nicole Arnold did with the food safety partnership thingies might have been good experience, but he got pressured into violating some basic research tenets: surveys, on their own, suck (they had limited cash), and press release before peer review is always a bad idea.

At least Chapman insisted all the raw data be made available.

The draconian consistency of partnership messages – cook, clean, chill, separate – while all valid, lead to a snake-oil salesman effect and ignore one of the biggest causes of foodborne illness that has been highlighted by both the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and the World Health Organization: food from unsafe sources.

What did consumers have to do with outbreaks involving peanut butter, pizza, pot pies, pet food, pepper and produce (washing don’t do much). That’s just the Ps.

Reciting prescriptive instructions like some fascist country line-dancing instructor benefits no one. Food safety is complex, and it takes effort.

The survey found that in today’s digital environment, most food safety education is done in person. According to the survey, 90 percent of the people that consider themselves food safety educators connect with consumers via face-to-face meetings and presentations. The next most-used channel is online, with 36 percent of educators using this method to connect with consumers.

But such a conclusion ignores the multiplier effect of messages, or the social amplification of risk: where did those messages originate and are they valid?

If anything the results argue for marketing microbial food safety at retail, where people can vote at the checkout aisle.

And education is the wrong word: people make risk-benefit decisions all the time. For those who care, food safety information should be provided using multiple media and messages; then people can decide for themselves.

At least Chapman stressed the need for medium and message evaluation, which is sorely lacking.

.jpg) microbial food safety hazards for fresh fruits and vegetables.” It and other documents are available in the foreign language versions on a special page on the agency’s website:www.FDA.gov/translations.

microbial food safety hazards for fresh fruits and vegetables.” It and other documents are available in the foreign language versions on a special page on the agency’s website:www.FDA.gov/translations. when disgust was far from the mainstream.

when disgust was far from the mainstream. because they often present dangers to public health.

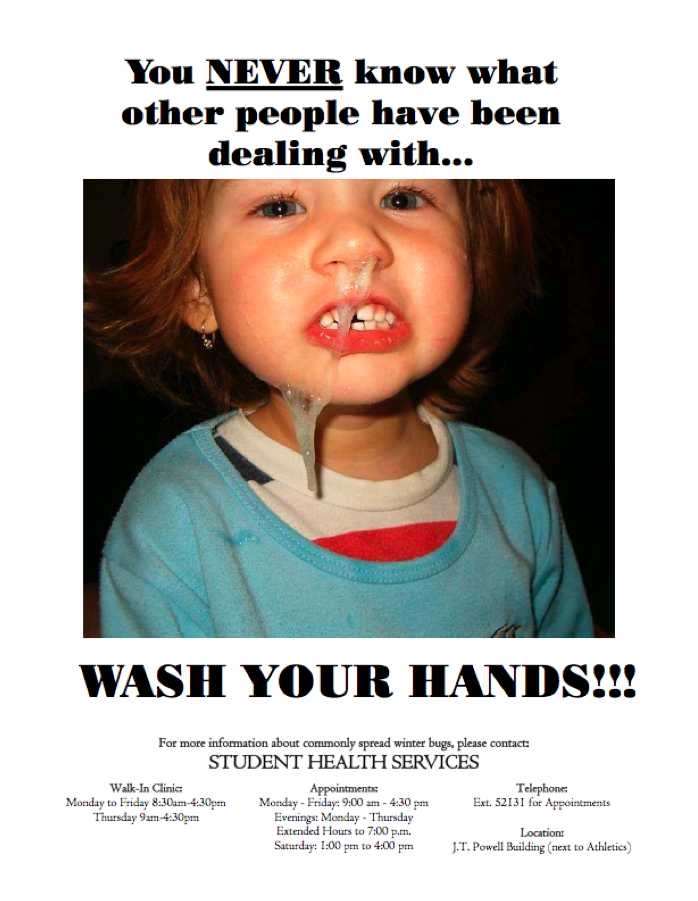

because they often present dangers to public health. our own work on food safety messages that lead to behavior change. We weren’t interested in self-reported surveys where everyone says they always wash their hands, but studies based on observed increases in handwashing compliance."

our own work on food safety messages that lead to behavior change. We weren’t interested in self-reported surveys where everyone says they always wash their hands, but studies based on observed increases in handwashing compliance.".jpg)

“Doug, I want you to talk about food safety messages that have been proven to work, that are supported by peer-reviewed evidence and lead to demonstrated behavior change,” or something like that.

“Doug, I want you to talk about food safety messages that have been proven to work, that are supported by peer-reviewed evidence and lead to demonstrated behavior change,” or something like that. Emily Rhoades and Jason D. Ellis write in the Journal of Food Safety that food safety in restaurants is an increasing concern among consumers. A primary population segment working in foodservice is receiving food safety information through new media channels such as video social network websites. This research used content analysis to examine the purpose and messages of food safety-related videos posted to YouTube. A usable sample of 76 videos was identified using “food safety” in the YouTube search function. Results indicate that videos must be artfully developed to attract YouTube users while conveying a credible and educational message. Communicators must also monitor new media for competing messages being viewed by target audiences and devise strategies to counter such messages. This one-time snapshot of how food safety was portrayed on YouTube suggests that the intended purpose of videos, whether educational or entertainment, is not as relevant as the perceived purpose and the message being received by viewers.

Emily Rhoades and Jason D. Ellis write in the Journal of Food Safety that food safety in restaurants is an increasing concern among consumers. A primary population segment working in foodservice is receiving food safety information through new media channels such as video social network websites. This research used content analysis to examine the purpose and messages of food safety-related videos posted to YouTube. A usable sample of 76 videos was identified using “food safety” in the YouTube search function. Results indicate that videos must be artfully developed to attract YouTube users while conveying a credible and educational message. Communicators must also monitor new media for competing messages being viewed by target audiences and devise strategies to counter such messages. This one-time snapshot of how food safety was portrayed on YouTube suggests that the intended purpose of videos, whether educational or entertainment, is not as relevant as the perceived purpose and the message being received by viewers. study during New Zealand’s influenza pandemic

study during New Zealand’s influenza pandemic