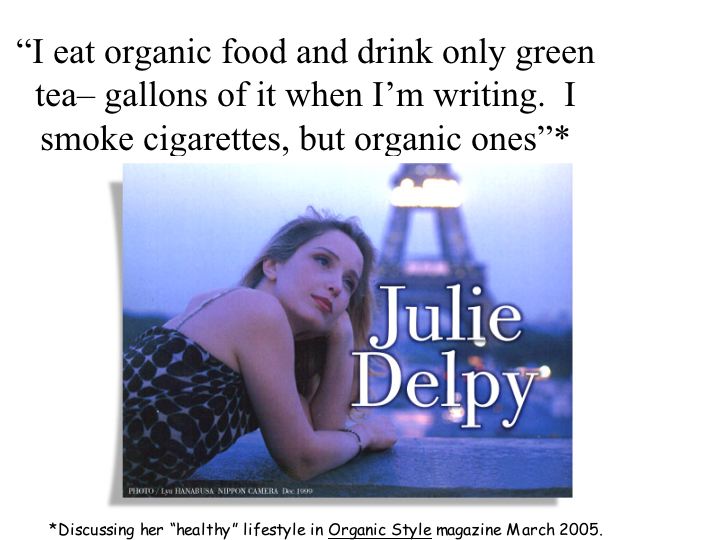

In the early part of the 2000s, media outlets seemed to be co-opted by the fantastical claims of the organic food sector. Organic was portrayed as safer, healthier and better for the environment.

There wasn’t a lot of data.

There wasn’t a lot of data.

There was a lot of food porn.

I had a student review and code 618 newspaper stories – it seems so quaint now, there were newspapers back then — reporting on or referencing organic food and organic agriculture from five North American media outlets from 1999-2004.

The paper was published in the British Food Journal yesterday.

Stacey found that of the 618 stories, 41.1 per cent were coded as being neutral, 36.9 per cent positive, 15.5 per cent mixed and 6.1 per cent negative.

From the discussion:

“It was determined that organic agriculture was often portrayed in the media as an alternative to allegedly unsafe and environmentally damaging modern agriculture practices — organic was defined by what it isn’t, rather than what it is. The National Post, for instance, published an article in 2002 about a report by Environmental Defence Canada, which had interpreted food safety  data from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and found that many products such as maple syrup and eggs did not meet safety standards. The article stated that, “to avoid health problems, Mary McGrath, the group’s director of research, suggested consumers consider purchasing organic or ecologically grown produce” (Sokoloff, 2002). Such unsubstantiated comments have become endemic in media coverage of all things organic.

data from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and found that many products such as maple syrup and eggs did not meet safety standards. The article stated that, “to avoid health problems, Mary McGrath, the group’s director of research, suggested consumers consider purchasing organic or ecologically grown produce” (Sokoloff, 2002). Such unsubstantiated comments have become endemic in media coverage of all things organic.

“The stories examined in this analysis frequently suggested organic production was void of many of the challenges faced by large-scale, modern agriculture, including pesticide residue, mad cow disease and genetic engineering.

Of the themes health, safety and environment, food safety was the least important in the discussion of organic agriculture in the media. … The finding that 50 per cent of food safety-themed statements in news articles were positive with respect to organic agriculture, while 81 per cent of health-themed statements and 90 per cent of environment-themed statements were positive towards organic food, indicates an uncritical press. USDA has repeatedly stated that the organic standard is a verification of production methods and not a food safety claim: ‘National standards for organic food will be released soon, and they will make clear that such products aren’t safer or more nutritious than conventional products, Agriculture Secretary Dan Glickman says’ (Brasher, 2000).”

The abstract is below.

Coverage of organic agriculture in North American newspapers: Media: linking food safety, the environment, human health and organic agriculture19.jul.10British Food Journal, Vol. 112 Iss: 7, pp.710 – 722

Stacey Cahill, Katija Morley, Douglas A. Powell

http://www.emeraldinsight.com/journals.htm?articleid=1871116&show=abstract

Abstract

Purpose – The project explored the ways in which the topics of organic food and agriculture are discussed in representative North American media outlets in reference to food safety, environmental concerns, and human health.

Purpose – The project explored the ways in which the topics of organic food and agriculture are discussed in representative North American media outlets in reference to food safety, environmental concerns, and human health.

Design/methodology/approach – Articles from five newspapers were collected and coded using the content analysis technique and analyzed for topic, tone, and theme.

Findings – For a six-year time period, 618 articles on organic food and organic agriculture are analyzed and the prominent topics are found to be genetic engineering, pesticides, and organic farming. Articles with a neutral tone with respect to organic agriculture and food accounted for 41.4 percent of the articles, while positively toned articles garnered 36.9 percent. The themes human health, food safety, and environmental concerns were discussed with positive reference to organic food and agriculture in 81, 50, and 90 percent, respectively, of comments pulled from the articles.

Practical implications – Analysis of these articles over time, between media outlets and by topic allows for understanding of media reporting on the subject and provides insight into the way the public is influenced by news coverage of organic food and agriculture.

Originality/value – Research that analyzes media coverage for how it portrays the topic of organic food and organic agriculture with respect to health, food safety, and environmental concern, and concludes that articles about organic production in the selected time period are seldom negative.

.jpg) of moving here.

of moving here.

my website, the current environment in which black-hearted enterprises make black-hearted foodstuffs and have a large market."

my website, the current environment in which black-hearted enterprises make black-hearted foodstuffs and have a large market." the E. coli O104 outbreak in sprouts last year that killed 53 was “minimal” and paled in comparison to the daily death toll of car accidents.

the E. coli O104 outbreak in sprouts last year that killed 53 was “minimal” and paled in comparison to the daily death toll of car accidents. making him the highest official to have made such blunt remarks toward food scandals. Food safety has been raised to the level of national strategy.

making him the highest official to have made such blunt remarks toward food scandals. Food safety has been raised to the level of national strategy. Powell, an associate professor of food safety, is the co-author of "Coverage of organic agriculture in North American newspapers: Media — linking food safety, the environment, human health and organic agriculture," just published in the British Food Journal.

Powell, an associate professor of food safety, is the co-author of "Coverage of organic agriculture in North American newspapers: Media — linking food safety, the environment, human health and organic agriculture," just published in the British Food Journal. "Food safety was the least important in the media discussion of organic agriculture," Powell said. "The finding that 50 percent of food safety-themed statements in news articles were positive with respect to organic agriculture, while 81 percent of health-themed statements and 90 percent of environment-themed statements were positive toward organic food, indicates an uncritical press."

"Food safety was the least important in the media discussion of organic agriculture," Powell said. "The finding that 50 percent of food safety-themed statements in news articles were positive with respect to organic agriculture, while 81 percent of health-themed statements and 90 percent of environment-themed statements were positive toward organic food, indicates an uncritical press." There wasn’t a lot of data.

There wasn’t a lot of data. data from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and found that many products such as maple syrup and eggs did not meet safety standards. The article stated that, “to avoid health problems, Mary McGrath, the group’s director of research, suggested consumers consider purchasing organic or ecologically grown produce” (Sokoloff, 2002). Such unsubstantiated comments have become endemic in media coverage of all things organic.

data from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and found that many products such as maple syrup and eggs did not meet safety standards. The article stated that, “to avoid health problems, Mary McGrath, the group’s director of research, suggested consumers consider purchasing organic or ecologically grown produce” (Sokoloff, 2002). Such unsubstantiated comments have become endemic in media coverage of all things organic. Emily Rhoades and Jason D. Ellis write in the Journal of Food Safety that food safety in restaurants is an increasing concern among consumers. A primary population segment working in foodservice is receiving food safety information through new media channels such as video social network websites. This research used content analysis to examine the purpose and messages of food safety-related videos posted to YouTube. A usable sample of 76 videos was identified using “food safety” in the YouTube search function. Results indicate that videos must be artfully developed to attract YouTube users while conveying a credible and educational message. Communicators must also monitor new media for competing messages being viewed by target audiences and devise strategies to counter such messages. This one-time snapshot of how food safety was portrayed on YouTube suggests that the intended purpose of videos, whether educational or entertainment, is not as relevant as the perceived purpose and the message being received by viewers.

Emily Rhoades and Jason D. Ellis write in the Journal of Food Safety that food safety in restaurants is an increasing concern among consumers. A primary population segment working in foodservice is receiving food safety information through new media channels such as video social network websites. This research used content analysis to examine the purpose and messages of food safety-related videos posted to YouTube. A usable sample of 76 videos was identified using “food safety” in the YouTube search function. Results indicate that videos must be artfully developed to attract YouTube users while conveying a credible and educational message. Communicators must also monitor new media for competing messages being viewed by target audiences and devise strategies to counter such messages. This one-time snapshot of how food safety was portrayed on YouTube suggests that the intended purpose of videos, whether educational or entertainment, is not as relevant as the perceived purpose and the message being received by viewers. We left Quebec City at 9 a.m. last Friday. National Public Radio Science Friday wanted me as a guest, and so did CNN. By 3:30 pm, we were in nowhere southwestern Ontario and I had to call the NPR studio — and they insisted on a landline.

We left Quebec City at 9 a.m. last Friday. National Public Radio Science Friday wanted me as a guest, and so did CNN. By 3:30 pm, we were in nowhere southwestern Ontario and I had to call the NPR studio — and they insisted on a landline..jpg)

The bacteria probably come from groundwater contaminated with animal faeces, he says. Once Salmonella gets on and into a tomato, the fruit acts like an incubator. Bacteria divide even in the cool temperatures of packing houses. "If you get a few samples into the internal tissue, then they will grow for sure," Warriner adds.

The bacteria probably come from groundwater contaminated with animal faeces, he says. Once Salmonella gets on and into a tomato, the fruit acts like an incubator. Bacteria divide even in the cool temperatures of packing houses. "If you get a few samples into the internal tissue, then they will grow for sure," Warriner adds. Last night, from 1-2 a.m. EST, I was the guest on

Last night, from 1-2 a.m. EST, I was the guest on