The dean of Canadian food and farm reporting, Jim Romahn, has written a powerful piece about the continuing failures in Canadian meat inspection – failures that had to be pointed out by Americans.

More than a year after 21 people died after eating Maple Leaf Foods Inc. products contaminated with Listeria monocytoges, the Canadian Food  Inspection Agency was failing to enforce its own standards and there was sloppy follow-up when hazardous conditions were identified.

Inspection Agency was failing to enforce its own standards and there was sloppy follow-up when hazardous conditions were identified.

Those worrisome facts are contained in a report prepared by two U.S. inspectors who visited in the fall of 2009 to check Canada’s compliance with its own standards. They visited headquarters in Ottawa, 23 meat-processing plants and two labs.

They found that the Canadian Food Inspection Agency generally has good manuals and intentions, but falls short at the plant level, including failures to identify lax sanitation and to enforce its standards.

Thirty years ago, when Canadian reporters began to obtain U.S. inspection reports on our packing plants, all of the deficiencies identified applied to specific problems and individual plants. This audit has identified similar deficiencies at the plant level, but far more serious, it found deficiencies in the overall system.

Had the U.S. inspectors not checked it’s likely that the deficiencies would have persisted, putting Canadian consumers at risk and the meat industry under threat of losing export markets.

The report also indicates some of the systemic deficiencies were identified during previous annual audits, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency promised to fix them, but they persisted. This is after the Maple Leaf crisis and frequent promises by Agriculture Minister Gerry Ritz and Prime Minister Stephen Harper that corrective action would be taken as swiftly as possible.

They have never talked about the U.S. audit reports that highlighted things that needed attention.

During the inspections of 23 plants – Canadian officials went along with the two U.S. officials – they identified problems so serious that three plants were banned from marketing their products in the U.S. and three more were issued warnings that they would be banned if they failed to immediately correct deficiencies.

Four of these six plants were processing ready-to-eat meat products, meaning they would go directly to consumers without any further steps to eliminate hazardous bacteria.

They also found by checking records that some of the plants were running overtime hours without any government inspectors checking conditions.

At another plant, they said the documents that indicated compliance “did not consistently reflect the conditions encountered at the time of the  audit.” Later in the report, they write “the actual conditions of the establishment visits were often not entirely consistent with the corresponding documentation.”

audit.” Later in the report, they write “the actual conditions of the establishment visits were often not entirely consistent with the corresponding documentation.”

Supervisors are supposed to periodically check the performance of front-line government inspectors, but the auditors found “system weaknesses . . . in the manner in which supervisory reviews were conducted.”

They also said there was “an inconsistent identification of potential non-compliances or potential inadequate performance by the inspection personnel.

“The deficiency concerning the lack of supervisory documentation is a repeat finding from the 2008 audit,” this report says.

The two U.S. auditors say the Canadian Food Inspection Agency needs to improve its communications its employee training and awareness and its feedback systems.

They found inspectors were failing to do their duties, as outlined in agency manuals, because they noticed:

– “Lack/loss of consistent identification of contaminated product and product-contact surfaces and other insanitary (sic) conditions.

– “Inconsistent verification of adequate corrective actions . . . with regards to repetitive non-compliances.

– “Inconsistent and loss of documentation of non-compliances in a manner that reflects actual establishment conditions, and

– “Lack/loss of increased inspection activities when non-compliance is observed . . .”

They add that “many of these findings are closely related to those identified during the previous audit.”

They also “identified system weaknesses regarding implementation and verification of HACCP (Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points) systems within the CFIA (Canadian Food Inspection Agency).”

More specifically, they identified “inaccurate analyzing of hazards” for HACCP protocols, “Inadequate implementation of basic elements of the HACCP plan, including monitoring and ongoing verification procedures” and “inappropriate verification of corrective actions taken in response to deviations from the critical limit (for harmful bacteria)”

In addition, they identified lapses in recording instances of non-compliance, such as failures to enter problems in the record book, failures to identify the level of bacterial contamination ad failure to record  the “actual times when the entries were made.” They also noted that border inspectors conducting spot checks of Canadian hamburger heading to customers in the U.S. found “several occurrences of zero-tolerance failures in addition to two positive results for E. coli O157:H7.”

the “actual times when the entries were made.” They also noted that border inspectors conducting spot checks of Canadian hamburger heading to customers in the U.S. found “several occurrences of zero-tolerance failures in addition to two positive results for E. coli O157:H7.”

Between Jan. 1 and Oct. 31, the U.S. border inspectors turned back 61 million pounds of Canadian meat, calling for repeat inspection by Canadians, and rejected 7,277 pounds that “involved food-safety concerns.” Labeling could be the problem with some of the shipments that were sent back.

In response to this audit, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency said it would increase inspections at 126 of the 190 plants certified to export to the U.S. There is no mention of what will happen at plants selling only to Canadians.

They say “supervisors are now required to accompany inspectors on a quarterly basis. . .”

“The sanitation task was re-structured to focus more on a global assessment of plant sanitation including more emphasis on Ready-to-Eat areas and equipment.”

The CFIA is also stepping up its training programs, its identification of critical control points for its HACCP protocols, its “Listeria related inspection tasks associated with operational/pre-operational sanitation, ventilation (e.g. condensation), building construction and maintenance of equipment.”

The CFIA also says “an electronic application is being developed to allow inspection staff access to historical data at the field level which will provide for more timely compliance decisions.”

When he was asked about the audit, Agriculture Minister Ritz said he has committed an additional $75 million to meat inspection since that audit was completed.

The results of the 2010 audit are not yet available from U.S. officials.

.jpg) Saturday retailers are willing to work with suppliers on reasonable cost increases related to improved meat product safety.

Saturday retailers are willing to work with suppliers on reasonable cost increases related to improved meat product safety..jpg) than those issued by the government, and the third-party assurances carry weight in the market.

than those issued by the government, and the third-party assurances carry weight in the market.

commercial. Such was the power of Oprah.

commercial. Such was the power of Oprah. expediting regulations prohibiting ruminant protein in ruminant feeds, boosting

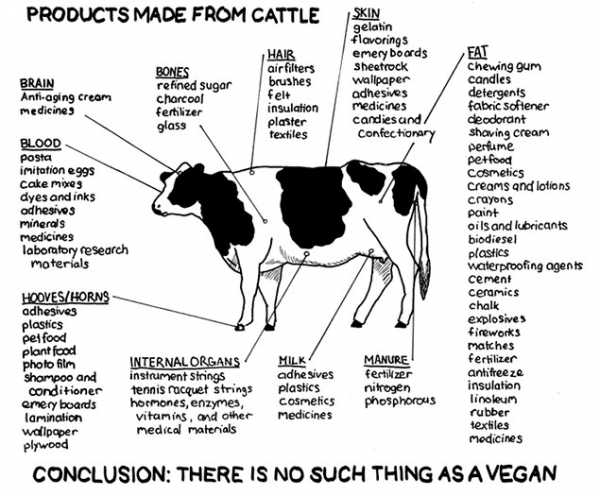

expediting regulations prohibiting ruminant protein in ruminant feeds, boosting longer stand) were rendered and fed to other cattle, and that BSE could make AIDS look like a common cold. The chief scientist for the U.S. National Cattleman’s Beef Association, rather than stressing the risk management actions that had been taken, was left arguing that cows were not vegetarians because they drank milk.

longer stand) were rendered and fed to other cattle, and that BSE could make AIDS look like a common cold. The chief scientist for the U.S. National Cattleman’s Beef Association, rather than stressing the risk management actions that had been taken, was left arguing that cows were not vegetarians because they drank milk. immediately washed, the skin is removed, and within minutes, the workers also remove the hooves, the hide and the head. The carcass is then moved to a giant cooler, where it stays for up to two days. After it’s been inspected and graded, it’s packaged, loaded on trucks and soon ends up in our local restaurants and stores.

immediately washed, the skin is removed, and within minutes, the workers also remove the hooves, the hide and the head. The carcass is then moved to a giant cooler, where it stays for up to two days. After it’s been inspected and graded, it’s packaged, loaded on trucks and soon ends up in our local restaurants and stores. committed to doing it right. And I believe that when animals are handled with dignity and harvested carefully, that’s the natural order of things,’ says Nicole.

committed to doing it right. And I believe that when animals are handled with dignity and harvested carefully, that’s the natural order of things,’ says Nicole.

.jpeg) menu items, but not at the expense of safety.”

menu items, but not at the expense of safety.”.jpg) Canadian Food Inspection Agency.

Canadian Food Inspection Agency. And why aren’t there more lion-meat tacos?

And why aren’t there more lion-meat tacos?

.jpg) obtained on Sept. 9.

obtained on Sept. 9. continental Concordia team, tested positive for clenbuterol during the 2010 Vuelta a Mexico.

continental Concordia team, tested positive for clenbuterol during the 2010 Vuelta a Mexico.(1).jpg)

and if they smelled okay, we re-wrapped them and put a new best-before date, extending usually by about five days. When we were told to change the best-before dates, I stopped buying any meat products from the Real Canadian Superstore."

and if they smelled okay, we re-wrapped them and put a new best-before date, extending usually by about five days. When we were told to change the best-before dates, I stopped buying any meat products from the Real Canadian Superstore." will complete a “thorough cleaning” of their facility “in the next several days.”

will complete a “thorough cleaning” of their facility “in the next several days.” Inspection Agency was failing to enforce its own standards and there was sloppy follow-up when hazardous conditions were identified.

Inspection Agency was failing to enforce its own standards and there was sloppy follow-up when hazardous conditions were identified. audit.” Later in the report, they write “the actual conditions of the establishment visits were often not entirely consistent with the corresponding documentation.”

audit.” Later in the report, they write “the actual conditions of the establishment visits were often not entirely consistent with the corresponding documentation.”