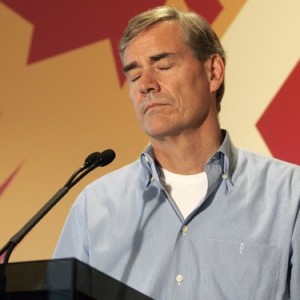

On Aug. 23, 2008, Maple Leaf CEO Michael McCain took to the Intertubes to apologize for an expanding outbreak of listeriosis that would eventually kill 22 people. As part of his speech, McCain said that Maple Leaf has “a strong culture of food safety.”

.jpg) On Aug. 27, 2008, McCain told a press conference,

On Aug. 27, 2008, McCain told a press conference,

“As I’ve said before, Maple Leaf Foods is 23,000 people who live in a culture of food safety. We have an unwavering commitment to keep our food safe, and we have excellent systems and processes in place.”

As laid bare in the Weatherill report on the 2008 listeria shit-fest, McCain’s invocation of food safety culture was as credible as the politicians and bureaucrats who lauded the workings of Canada’s food safety surveillance system, when it didn’t actually work at all.

Andre Picard, the long-time health reporter for Toronto’s Globe and Mail, picked up on this theme today when he wrote,

“the root of the listeriosis outbreak in Canada in 2008 was not two dirty meat slicers but rather a culture – in government and private enterprise alike – in which food safety was not a priority but an afterthought.”

Picard says Ms. Weatherill’s most important recommendation – one that has been largely glossed over in media coverage of the report – is for a culture of safety or, as is stated bluntly in the report: “Actions, not words.”

Really, Canada, this is nothing new. There is a long history in developed countries of negligence, followed by remorse, promises to do better and … minimal changes. Didn’t Canada go through all this after E. coli O157:H7 entered the municipal water supply in Walkerton, Ontario in 2000, killing 7 and sickening 2,500 in a town of 5,000?

In 1985, 19 of 55 affected people at a London, Ontario, nursing home died after eating sandwiches infected with E. coli O157:H7. On Oct. 12, 1985, in response to an inquest, the Ontario government announced a training program for food-handlers in health-care institutions, “stressing cleaning and sanitizing procedures and hygienic practices in food preparation.” That training apparently didn’t include the food safety basic – don’t give unheated cold cuts to vulnerable populations, like old people, ‘cause they may die from listeria.

These days, food safety culture is the buzz. The same recommendation – to embrace and enhance food safety culture — was embraced by the U.K. Food Standards Agency last week following an inquiry into the death of 5-year-old Mason Jones and the illness of 160 other schoolchildren who consumed E. coli O157:H7 contaminated cold cuts in Wales in 2005.

These days, food safety culture is the buzz. The same recommendation – to embrace and enhance food safety culture — was embraced by the U.K. Food Standards Agency last week following an inquiry into the death of 5-year-old Mason Jones and the illness of 160 other schoolchildren who consumed E. coli O157:H7 contaminated cold cuts in Wales in 2005.

Sixteen years after E. coli O157:H7 killed four and sickened hundreds who ate hamburgers at the Jack-in-the-Box chain, the challenge remains: how to get people to take food safety seriously? ??????Lots of companies do take food safety seriously and the bulk of Western meals are microbiologically safe. But recent food safety failures have been so extravagant, so insidious and so continual that consumers must feel betrayed.??????

Culture encompasses the shared values, mores, customary practices, inherited traditions, and prevailing habits of communities. The culture of today’s food system (including its farms, food processing facilities, domestic and international distribution channels, retail outlets, restaurants, and domestic kitchens) is saturated with information but short on behavioral-change insights. Creating a culture of food safety requires application of the best science with the best management and communication systems, including compelling, rapid, relevant, reliable and repeated, multi-linguistic and culturally-sensitive messages.

Frank Yiannas, the vice-president of food safety at Wal-Mart writes in his 2008 book, Food Safety Culture: Creating a Behavior-based Food Safety Management System, that an organization’s food safety systems need to be an integral part of its culture.

The other guru of food safety culture, Chris Griffith of the University of Wales, features prominently in the report by Professor Hugh Pennington into the 2005 E.coli outbreak in Wales.

I’ve maintained for 16 years that, despite high-profile outbreaks and unacceptable loss of life, food safety in Canada is, as Weatherill stated, an afterthought.

Forget government. Michael McCain, you want to be a leader, lead, don’t just talk about it by throwing around words like food safety culture because they are suddenly fashionable.

The best food producers, processors, retailers and restaurants will go above and beyond minimal government and auditor standards and sell food safety solutions directly to the public. The best organizations will use their own people to demand ingredients from the best suppliers; use a mixture of encouragement and enforcement to foster a food safety culture; and use technology to be transparent — whether it’s live webcams in the facility or real-time test results on the website — to help restore the shattered trust with the buying public.

The best food producers, processors, retailers and restaurants will go above and beyond minimal government and auditor standards and sell food safety solutions directly to the public. The best organizations will use their own people to demand ingredients from the best suppliers; use a mixture of encouragement and enforcement to foster a food safety culture; and use technology to be transparent — whether it’s live webcams in the facility or real-time test results on the website — to help restore the shattered trust with the buying public.

And the best cold-cut companies may stop dancing around and tell pregnant women, old people and other immunocompromised folks, don’t eat this food unless it’s heated.

Weatherill says, action not words.

someone someday

someone someday(1).jpeg) Or as Rick Holley of the University of Manitoba says,

Or as Rick Holley of the University of Manitoba says, (1).jpg) Inc., quickly issued a recall of what would become 35 million pounds of hot dogs and other packaged meats produced at the company’s only plant in Michigan. By Christmas, testing of unopened packages of hot dogs from Bil Mar detected the same genetically unique L. monocytegenes bacteria, and production at the plant was halted.

Inc., quickly issued a recall of what would become 35 million pounds of hot dogs and other packaged meats produced at the company’s only plant in Michigan. By Christmas, testing of unopened packages of hot dogs from Bil Mar detected the same genetically unique L. monocytegenes bacteria, and production at the plant was halted..jpg) On Aug. 27, 2008, McCain told a press conference

On Aug. 27, 2008, McCain told a press conference These days, food safety culture is the buzz

These days, food safety culture is the buzz The best food producers, processors, retailers and restaurants will go above and beyond minimal government and auditor standards and sell food safety solutions directly to the public. The best organizations will use their own people to demand ingredients from the best suppliers; use a mixture of encouragement and enforcement to foster a food safety culture; and use technology to be transparent — whether it’s live webcams in the facility or real-time test results on the website — to help restore the shattered trust with the buying public.

The best food producers, processors, retailers and restaurants will go above and beyond minimal government and auditor standards and sell food safety solutions directly to the public. The best organizations will use their own people to demand ingredients from the best suppliers; use a mixture of encouragement and enforcement to foster a food safety culture; and use technology to be transparent — whether it’s live webcams in the facility or real-time test results on the website — to help restore the shattered trust with the buying public..jpg)

Michael McCain, president and CEO of Maple Leaf Foods, took not only to the airwaves but to the Intertubes to convey his empathy and resolve at fixing the listeria situation. It’s an excellent piece of risk communication.

Michael McCain, president and CEO of Maple Leaf Foods, took not only to the airwaves but to the Intertubes to convey his empathy and resolve at fixing the listeria situation. It’s an excellent piece of risk communication.