Shed no crocodile tears for Sally Jackson and her E. coli O157:H7 contaminated cheese.

The infractions documented by U.S. Food and Drug Administration inspectors last week — after the recall and with inspectors knowingly present – would make anyone wonder why the fancy restaurants and retailers like Whole Foods would buy cheese made with crap. Sally Jackson and staff were seen to:

• Not wash and sanitize hands thoroughly in an adequate hand-washing facility after each absence from the work station and at any time their hands  may have become soiled or contaminated. Specifically, the owner was observed throughout the day to altemately perform cheese making functions, such as stirring cheese curd with bare hands and wrapping cheese in grape leaves, with outside activities, such as milking/feeding livestock, without any hand washing being observed.

may have become soiled or contaminated. Specifically, the owner was observed throughout the day to altemately perform cheese making functions, such as stirring cheese curd with bare hands and wrapping cheese in grape leaves, with outside activities, such as milking/feeding livestock, without any hand washing being observed.

• Failure to provide handwashing facilities at each location in the plant where needed. Specifically, the approximately 10 inch diameter, shallow bowl handsink in the vestibule is too small for proper use, The sink drain pipe and water supply lines were disconnected.

• Failure to use water which is of adequate sanitary quality in food and on food-contact surfaces. Specifically, the well water supply for the facility is not currently in microbiological compliance. The most recent water analysis was unsatisfactory for total colifom as evidenced by a test report from 10/4/10 observed at the facility. The well has not been retested.

• Failure to clean non-food-contaet surfaces of equipment as frequently as necessary to protect against contamination. Specifically, the wood fixtures, walls and floors were generally soiled and stained with grime/dirt. The floors also showed an accumulation of manure, mud. straw.

• Suitable outer garments are not worn that protect against contamination of food, food contact surfaces, and food packaging materials. Specifically, the owner wore manure-soiled outer clothing during the production of cheese; handling utensils and direct handling of finished product. Owner was observed kneeling in fresh cow manure, while milking a cow outside, then .jpg) brushed pants with a bare hand and was later observed standing over a bucket of drained curd in the cheese room with the soiled pants coming in to contact with the edge of the bucket.

brushed pants with a bare hand and was later observed standing over a bucket of drained curd in the cheese room with the soiled pants coming in to contact with the edge of the bucket.

This could be an exaggeration, but it sounds like Sally Jackson was making cheese while covered in cow shit. Guess it’s all-natural.

Nancy Leson of the Seattle Times reports that Jackson, the Oroville, Washington, cheesemaker whose name has been associated with some of Washington’s finest milk product for 30 years, will shut down her business, after the Food and Drug Administration confirmed that Jackson’s cheese, made from unpasteurized, raw milk, had sickened eight people in four states.

"My argument then was that I have never made anybody sick in 30 years," Jackson said. "That’s what breaks my heart now, that this is how it ended."

That’s a terrible argument, and one I hear routinely. E. coli O157:H7 has been known as a source of human illness for about 29 years, but only in the past 15 years have DNA fingerprinting techniques evolved so that outbreaks are more often linked to a specific food.

The results from the FDA inspection and the sick people also show the fallacies of such an argument.

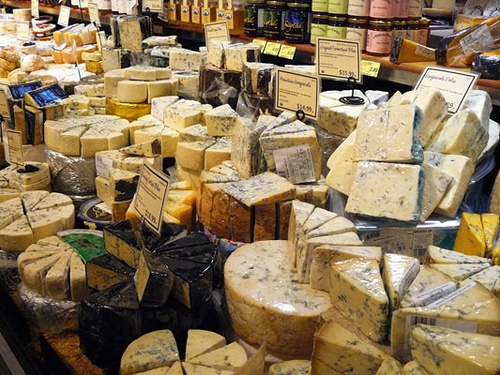

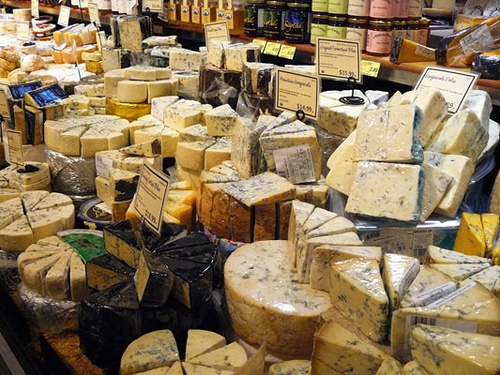

But why hadn’t anyone noticed? Whole Foods sold – and is now recalling — Sally Jackson cheese from retail outlets in California, Nevada, Washington .jpg) and Washington, D.C.

and Washington, D.C.

“The recalled cheese came from its supplier, Sally Jackson Cheese of Oroville, Wash and was cut and packaged in clear plastic wrap and sold with a Whole Foods Market scale label. Some labels also list Sally Jackson. The affected products are: cow, goat and sheep milk cheese; cow and sheep milk cheese wrapped in chestnut leaves; and goat milk cheese wrapped in grape leaves.”

Where were the Whole Foods safety auditors who approved Sally Jackson raw milk cheese on their shelves? Whole Foods sucks at food safety.

Sean O’Neill of Goshen Stampede, Inc. says they see about 25,000 people come through the fairgrounds, and they come from all over.

Sean O’Neill of Goshen Stampede, Inc. says they see about 25,000 people come through the fairgrounds, and they come from all over.

regarding food vendors present and cattle used at the rodeos. Environmental samples were collected from rodeo grounds. Two-enzyme pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA) were performed on isolates.

regarding food vendors present and cattle used at the rodeos. Environmental samples were collected from rodeo grounds. Two-enzyme pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA) were performed on isolates.

.jpg) liquid fertilizer touted as made from all-natural products such as fish meal and bird guano that instead was spiked with far cheaper synthetic chemicals.

liquid fertilizer touted as made from all-natural products such as fish meal and bird guano that instead was spiked with far cheaper synthetic chemicals. may have become soiled or contaminated. Specifically, the owner was observed throughout the day to altemately perform cheese making functions, such as stirring cheese curd with bare hands and wrapping cheese in grape leaves, with outside activities, such as milking/feeding livestock, without any hand washing being observed.

may have become soiled or contaminated. Specifically, the owner was observed throughout the day to altemately perform cheese making functions, such as stirring cheese curd with bare hands and wrapping cheese in grape leaves, with outside activities, such as milking/feeding livestock, without any hand washing being observed. .jpg) brushed pants with a bare hand and was later observed standing over a bucket of drained curd in the cheese room with the soiled pants coming in to contact with the edge of the bucket.

brushed pants with a bare hand and was later observed standing over a bucket of drained curd in the cheese room with the soiled pants coming in to contact with the edge of the bucket..jpg) and water treated with manure, the bacteria can survive and are active in the rhizosphere, or the area around the plant roots, of lettuce and radishes. E. coli eventually gets onto the aboveground surfaces of the plants, where it can live for several weeks.

and water treated with manure, the bacteria can survive and are active in the rhizosphere, or the area around the plant roots, of lettuce and radishes. E. coli eventually gets onto the aboveground surfaces of the plants, where it can live for several weeks. Christine Bushway, Executive Director of the Organic Trade Association (OTA) says “organic agriculture is the most highly regulated system of agricultural production in the U.S., and the USDA-accredited verification system, especially its recordkeeping and inspection requirements, should be recognized and considered by FDA when drafting rules requiring similar features.”

Christine Bushway, Executive Director of the Organic Trade Association (OTA) says “organic agriculture is the most highly regulated system of agricultural production in the U.S., and the USDA-accredited verification system, especially its recordkeeping and inspection requirements, should be recognized and considered by FDA when drafting rules requiring similar features.”.jpg) Increased attention has been focused on fresh fruits and vegetables, especially raw or minimally processed, as a significant source of foodborne illness. Outbreaks have been linked to both conventionally and organically grown produce. This paper outlines the risks associated with fresh produce, common pathways of contamination, and current trends in organic agriculture. The primary objective was to determine whether the Canadian General Standards Board (CGSB) organic standard is consistent with the production of microbiologically safe produce and to examine the potential for the CGSB organic standard to include considerations for microbial food safety. This objective was achieved by examining information gaps between the US Food and Drug Administration on-farm food safety guidelines and the organic standard developed by the CGSB. This examination showed a significant degree of commonality and, in some cases, it was demonstrated that microbial food safety standards are achieved indirectly under organic production. The main difference between the U.S. guidelines and the CGSB standard is the focus on the process rather than the safety of the final product,and the lack of discussion of microbial considerations in the CGSB standard. Specific omissions include worker hygiene and recommendations for safe use of processing and irrigation water. The production of safe food is the responsibility of everyone in the farm-to-fork chain. With established relationships between growers and regulatory infrastructure, the CGSB organic standard would be an ideal vehicle for providing organic growers with information and guidelines on identifying and controlling microbial hazards on their produce.

Increased attention has been focused on fresh fruits and vegetables, especially raw or minimally processed, as a significant source of foodborne illness. Outbreaks have been linked to both conventionally and organically grown produce. This paper outlines the risks associated with fresh produce, common pathways of contamination, and current trends in organic agriculture. The primary objective was to determine whether the Canadian General Standards Board (CGSB) organic standard is consistent with the production of microbiologically safe produce and to examine the potential for the CGSB organic standard to include considerations for microbial food safety. This objective was achieved by examining information gaps between the US Food and Drug Administration on-farm food safety guidelines and the organic standard developed by the CGSB. This examination showed a significant degree of commonality and, in some cases, it was demonstrated that microbial food safety standards are achieved indirectly under organic production. The main difference between the U.S. guidelines and the CGSB standard is the focus on the process rather than the safety of the final product,and the lack of discussion of microbial considerations in the CGSB standard. Specific omissions include worker hygiene and recommendations for safe use of processing and irrigation water. The production of safe food is the responsibility of everyone in the farm-to-fork chain. With established relationships between growers and regulatory infrastructure, the CGSB organic standard would be an ideal vehicle for providing organic growers with information and guidelines on identifying and controlling microbial hazards on their produce. Contaminated water must also be kept away from bagged produce that is not heat-treated, the Codex experts said, fixing new benchmarks that could change production and harvesting norms across the world.

Contaminated water must also be kept away from bagged produce that is not heat-treated, the Codex experts said, fixing new benchmarks that could change production and harvesting norms across the world. When a bucket in one of his five bathrooms is full, he empties it in the compost pile in his backyard in rural Pennsylvania. Eventually he takes the resulting soil and spreads it over his vegetable garden as fertilizer.

When a bucket in one of his five bathrooms is full, he empties it in the compost pile in his backyard in rural Pennsylvania. Eventually he takes the resulting soil and spreads it over his vegetable garden as fertilizer.