The U.S. Interagency Working Group on Import Safety has issued its report to President Bush with the snappy title, Protecting American Consumers Every Step of the Way: A strategic framework for continual improvement in import safety.

The U.S. Interagency Working Group on Import Safety has issued its report to President Bush with the snappy title, Protecting American Consumers Every Step of the Way: A strategic framework for continual improvement in import safety.

The report outlines an approach that can build upon existing efforts to improve the safety of imported products, while facilitating trade.

Approximately $2 trillion of imported products entered the United States economy last year and experts project that this amount will triple by 2015. … While we acknowledge it is not possible to eliminate all risk with imported and domestic products, being smarter requires us to find new ways to protect American consumers and continually improve the safety of our imports. We recommend working with the importing community to develop approaches that consider risks over the life cycle of an imported product, and that focus actions and resources to minimize the likelihood of unsafe products reaching U.S. consumers. …

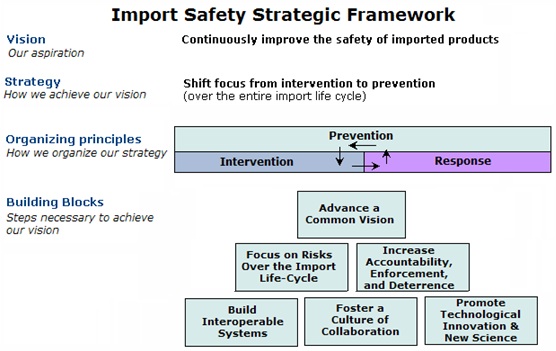

Supporting this model are six building blocks: 1) Advance a common vision, 2) Increase accountability, enforcement and deterrence,

3) Focus on risks over the life cycle of an imported product, 4) Build interoperable systems, 5) Foster a culture of collaboration, and 6) Promote technological innovation and new science.

The Wall Street Journal reports that the Food and Drug Administration would be granted power to require manufacturers and importers of "high risk" products to take steps to prevent contamination and other problems. The FDA could require producers and importers of such goods to certify they comply with FDA standards. The FDA could bar imports if it is given no access or only limited access to production records. The agency would also be able to mandate recalls on tainted products, something it can’t do now.

At least the panel got this bit right:

"Americans benefit from one of the safest food supplies and among the highest standards of consumer protection in the world. Our task is to build on this solid foundation by identifying actions for both the public and private sectors that will help our import safety system continually improve and adapt to a rapidly growing and changing global economy."

Not the safest, which is difficult to substantiate, but one of the safest.

There’s no real surprises in the report, it all sounds good, but really, government is limited in what it can do. And I’m not sure what they mean by focusing on high-risk products. Anything can be high-risk depending on how it was produced — pot pies, peanut butter and pepperoni come to mind. And those were all foodborne illness outbreaks associated with domestic products. Food from around the corner or around the globe has the potential to be contaminated with dangerous microorganisms. Focusing on imports may detract from efforts at home. A strong food safety culture may translate to fewer sick people.

No.

No. .jpg) I expressed a similar notion this morning in the

I expressed a similar notion this morning in the  Joel Rubin of the

Joel Rubin of the  President Jon Wefald likes to remind me that Kansas State University will not be getting a hockey arena any time soon. I even gave him one of our collectors T-shirts (left, exactly as shown) and he said, no way.

President Jon Wefald likes to remind me that Kansas State University will not be getting a hockey arena any time soon. I even gave him one of our collectors T-shirts (left, exactly as shown) and he said, no way..jpg)

the key to growing is to be an eager learner. One cutting-edge difference in the best leaders I’ve been around is that they truly are avid learners."

the key to growing is to be an eager learner. One cutting-edge difference in the best leaders I’ve been around is that they truly are avid learners." Despite being universally panned by critics and avoided by moviegoers, I finally saw

Despite being universally panned by critics and avoided by moviegoers, I finally saw  The

The  Researchers report in the latest Australian and New Zealand Journal of Health that in a survey of 586 women attending antenatal clinics in one private and two major public hospitals in New South Wales between April and November 2006,

Researchers report in the latest Australian and New Zealand Journal of Health that in a survey of 586 women attending antenatal clinics in one private and two major public hospitals in New South Wales between April and November 2006,  Some students groups are upset after the University of Nebraska at Omaha banned the sale of homemade baked goods on campus.

Some students groups are upset after the University of Nebraska at Omaha banned the sale of homemade baked goods on campus. Amy has survival skills. She knows how to field-dress animals. And has pretty good bowstaff skills.

Amy has survival skills. She knows how to field-dress animals. And has pretty good bowstaff skills.