The paper was published in July 2009 but the U.S. Department of Agriculture put out a press release today saying that Escherichia coli is not likely to contaminate the internal vascular structure of field-grown leafy greens and thus increase the incidence of foodborne illness.

The timing was probably coupled with pretty pictures of the research, appearing in the April 2011 issue of USDA’s Agricultural Research magazine.

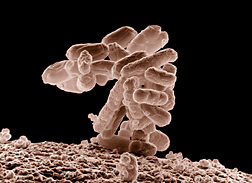

Agricultural Research Service (ARS) microbiologist Manan Sharma wanted to find out if plant roots could draw in E. coli pathogens from the soil when taking in nutrients and water. He and colleagues modified several types of E. .jpg) coli—including some highly pathogenic strains that cause foodborne illness—by adding a gene for fluorescence. This allowed them to track the pathogen’s journey from the field to the produce.

coli—including some highly pathogenic strains that cause foodborne illness—by adding a gene for fluorescence. This allowed them to track the pathogen’s journey from the field to the produce.

The team, which is located at the ARS Environmental Microbial and Food Safety Laboratory in Beltsville, Md., confirmed that the pathogenic E. coli could survive in the soil for up to 28 days. They also observed that the fluorescent E. coli cells were capable of migrating into the roots of spinach plants.

The researchers also examined baby spinach plants over the course of 28 days after germination to see if any of the E. coli strains were taken up past the roots and into the plant’s interior structures. For this part of the study, they grew baby spinach in pasteurized soil and hydroponic media.

At day 28, there was no evidence that the E. coli had become "internalized" in leaves or shoots of baby spinach plants grown in the pasteurized soil. E. coli could be detected in hydroponically-grown spinach samples, but its survival in shoot tissue was sporadic 28 days after the plants had germinated.

These findings strongly suggest that although E. coli can survive in soils, it’s highly unlikely that foodborne illness would result from the bacterium becoming "internalized" through roots in leafy produce.

Chapman reviewed the idea of internalization of human pathogens by plants for barfblog in 2008 and it’s available at

http://barfblog.foodsafety.ksu.edu/blog/139669/08/05/28/pathogens-produce-brief-review

The original abstract is below:

A novel approach to investigate the uptake and internalization of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in spinach cultivated in soil and hydroponic medium.

Sharma M, Ingram DT, Patel JR, Millner PD, Wang X, Hull AE, Donnenberg MS.

J Food Prot. 2009 Jul;72(7):1513-20.

Internalization of Escherichia coli O157:H7 into spinach plants through root uptake is a potential route of contamination. A Tn7-based plasmid vector was used to insert a green fluorescent protein gene into the attTn7 site in the E. coli chromosome. Three green fluorescent protein-labeled E. coli inocula were used:  produce outbreak O157:H7 strains RM4407 and RM5279 (inoculum 1), ground beef outbreak O157:H7 strain 86-24h11 (inoculum 2), and commensal strain HS (inoculum 3). These strains were cultivated in fecal slurries and applied at ca. 10(3) or 10(7) CFU/g to pasteurized soils in which baby spinach seedlings were planted. No E. coli was recovered by spiral plating from surface-sanitized internal tissues of spinach plants on days 0, 7, 14, 21, and 28. Inoculum 1 survived at significantly higher populations (P < 0.05) in the soil than did inoculum 3 after 14, 21, and 28 days, indicating that produce outbreak strains of E. coli O157:H7 may be less physiologically stressed in soils than are nonpathogenic E. coli isolates. Inoculum 2 applied at ca. 10(7) CFU/ml to hydroponic medium was consistently recovered by spiral plating from the shoot tissues of spinach plants after 14 days (3.73 log CFU per shoot) and 21 days (4.35 log CFU per shoot). Fluorescent E. coli cells were microscopically observed in root tissues in 23 (21%) of 108 spinach plants grown in inoculated soils. No internalized E. coli was microscopically observed in shoot tissue of plants grown in inoculated soil. These studies do not provide evidence for efficient uptake of E. coli O157:H7 from soil to internal plant tissue.

produce outbreak O157:H7 strains RM4407 and RM5279 (inoculum 1), ground beef outbreak O157:H7 strain 86-24h11 (inoculum 2), and commensal strain HS (inoculum 3). These strains were cultivated in fecal slurries and applied at ca. 10(3) or 10(7) CFU/g to pasteurized soils in which baby spinach seedlings were planted. No E. coli was recovered by spiral plating from surface-sanitized internal tissues of spinach plants on days 0, 7, 14, 21, and 28. Inoculum 1 survived at significantly higher populations (P < 0.05) in the soil than did inoculum 3 after 14, 21, and 28 days, indicating that produce outbreak strains of E. coli O157:H7 may be less physiologically stressed in soils than are nonpathogenic E. coli isolates. Inoculum 2 applied at ca. 10(7) CFU/ml to hydroponic medium was consistently recovered by spiral plating from the shoot tissues of spinach plants after 14 days (3.73 log CFU per shoot) and 21 days (4.35 log CFU per shoot). Fluorescent E. coli cells were microscopically observed in root tissues in 23 (21%) of 108 spinach plants grown in inoculated soils. No internalized E. coli was microscopically observed in shoot tissue of plants grown in inoculated soil. These studies do not provide evidence for efficient uptake of E. coli O157:H7 from soil to internal plant tissue.

and hundreds of thousands of E. coli bacteria were found in samples of one gram, about the size of a small leaf.

and hundreds of thousands of E. coli bacteria were found in samples of one gram, about the size of a small leaf. Southern California, according to California Department of Public Health director Dr. Mark Horton.

Southern California, according to California Department of Public Health director Dr. Mark Horton. .jpg) and water treated with manure, the bacteria can survive and are active in the rhizosphere, or the area around the plant roots, of lettuce and radishes. E. coli eventually gets onto the aboveground surfaces of the plants, where it can live for several weeks.

and water treated with manure, the bacteria can survive and are active in the rhizosphere, or the area around the plant roots, of lettuce and radishes. E. coli eventually gets onto the aboveground surfaces of the plants, where it can live for several weeks..jpg) the produce industry is in food safety together. ?

the produce industry is in food safety together. ? locate possible problems — a leaky fertilizer bin, an unexpected pathogen in the water, unwashed hands on a factory floor — and more quickly halt the spread of contaminated food.

locate possible problems — a leaky fertilizer bin, an unexpected pathogen in the water, unwashed hands on a factory floor — and more quickly halt the spread of contaminated food. which it claims is many times more effective in killing bacteria. The new wash solution, called FreshRinse, contains organic acids commonly used in the food industry, including lactic acid, a compound found in milk.

which it claims is many times more effective in killing bacteria. The new wash solution, called FreshRinse, contains organic acids commonly used in the food industry, including lactic acid, a compound found in milk.

pre-packaged salad mix.

pre-packaged salad mix.

Fresh Express is voluntarily recalling certain Romaine lettuce salad products

Fresh Express is voluntarily recalling certain Romaine lettuce salad products