The risk may be small, but the failures are tragic.

Governments routinely warn that immunocompromised people, including expectant mothers and the elderly, should refrain from certain ready-to-eat refrigerated foods like deli meats and smoked salmon because of the risk of listeriosis.

Elizabeth Weise writes in today’s USA Today that the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been saying for at least 11 years now that people over 50 and especially those .jpeg) over 65 should avoid hot dogs, lunch meats, cold cuts and other deli meats unless they are reheated to 165 degrees — "steaming hot" in CDC’s words.

over 65 should avoid hot dogs, lunch meats, cold cuts and other deli meats unless they are reheated to 165 degrees — "steaming hot" in CDC’s words.

The government also says you shouldn’t keep an open package of sliced deli meat more than five days, all to reduce the risk of infection from a bacteria called listeria. But some question whether the country’s been paying attention.

Barbara Resnick, incoming president of the American Geriatrics Society and a professor of nursing at the University of Maryland, knows of no one over that age who heats deli meats to that level and says she’s never seen a case of listeriosis in a patient.

Neil Gaffney, spokesman for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety Inspection Service said, "When it comes to food safety, we’re serious: People at risk for listeriosis should not eat hot dogs, luncheon meats or deli meats unless they are reheated until steaming hot. Thoroughly reheating food can help kill any bacteria that might be present. If you cannot reheat these foods, do not eat them."

Mike Doyle, a professor of food microbiology at the University of Georgia said about 85% of listeriosis cases are linked to cold cuts or deli meats, and that today almost all packaged lunch meats contain either added sodium lactate, an acid formed by fermentation, or potassium lactate, fermented from sugar, as antimicrobials. That’s what he looks for when he buys cold cuts.

And based on FSIS risk-assessment data, meats sliced at the store pose a greater risk than meats pre-sliced at federally inspected establishments

Listeria and cold cuts were ranked just last week as the third worst combination of a food and a pathogen in terms of the burden they place on public health, costing $1.1 billion a year in medical costs and lost work days, according to a study by the University of Florida’s Emerging Pathogen Institute.

Douglas Powell a professor of food safety at Kansas State University, said, "And you can’t see, taste or smell that it’s there.”

CDC also says don’t keep opened packages of lunch meat, or meat sliced at the local deli, for l.jpeg) onger than three to five days. That’s another one no one pays attention to, says Kansas’ Powell.

onger than three to five days. That’s another one no one pays attention to, says Kansas’ Powell.

"Anecdotally, lots of people keep cold cuts in their refrigerator far longer than they should. People keep them for one to two weeks. That’s the key message. If you get it from the deli counter, four days max."

What wasn’t included in the story is evidence of listeria-related tragedies in other countries – countries that may not have approved those listeria-restraining additives.

Twenty-three elderly people died in Canada in 2008 after eating listeria-laden cold-cuts from Maple Leaf Foods. Later that year, listeria in soft cheese in Quebec led to 38 hospitalizations, of which 13 were pregnant and gave birth prematurely. Two adults died and there were 13 perinatal deaths.

The New South Wales Food Authority said last month the Authority provides information on listeria to pregnant women to allow them to make an informed food choice regarding the risk and how to minimize it. It is not to say that every piece of deli meat has Listeria on it, but some foods have a higher potential rate of contamination than others, and it is better to avoid them.

The risk of acquiring listeriosis is low. However the consequences for a pregnant woman contracting listeriosis are dire.

While the Authority may be accused of ‘being over the top’, we may also be accused of neglecting pregnant women if we did not provide this information so pregnant women could .jpeg) make informed choices in what they eat.

make informed choices in what they eat.

Over the last 5 years in Australia there have been between 4 and 14 cases of listeriosis diagnosed in pregnant women or their babies each year. These infections have resulted in the deaths of 8 fetuses or newborn babies.

which became stuck in their throat and required a trip to hospital to have it removed, after eating food straight out of a take-away container, which had "softened" as a result of their meal being heated up in a microwave oven.

which became stuck in their throat and required a trip to hospital to have it removed, after eating food straight out of a take-away container, which had "softened" as a result of their meal being heated up in a microwave oven. the liar really care about the facts but the bullshitter isn’t concerned with the facts except insofar as they may be pertinent to his interest in getting away with what he says: “He does not care whether the things he says describe reality correctly. He just picks them up, or makes them up, to suit his purposes.”

the liar really care about the facts but the bullshitter isn’t concerned with the facts except insofar as they may be pertinent to his interest in getting away with what he says: “He does not care whether the things he says describe reality correctly. He just picks them up, or makes them up, to suit his purposes.” sustainable — it is not), brown eggs (trying to create the impression they are different nutritionally from white eggs — they are not), and non-GMO (trying to create the impression the product is safer — it is not).

sustainable — it is not), brown eggs (trying to create the impression they are different nutritionally from white eggs — they are not), and non-GMO (trying to create the impression the product is safer — it is not). falsely labeled as U.S. wild caught shrimp and selling shrimp that falsely claimed to be larger and more expensive than they actually were; and for buying fish they knew had been illegally imported into the United States. Some of the fish tested positive for malachite green and Enrofloxin, both of which are considered health hazards and banned from U.S. food products.

falsely labeled as U.S. wild caught shrimp and selling shrimp that falsely claimed to be larger and more expensive than they actually were; and for buying fish they knew had been illegally imported into the United States. Some of the fish tested positive for malachite green and Enrofloxin, both of which are considered health hazards and banned from U.S. food products..jpg) Orange counties.

Orange counties. cartons it was impossible to determine if they were free range or not.

cartons it was impossible to determine if they were free range or not. and if they smelled okay, we re-wrapped them and put a new best-before date, extending usually by about five days. When we were told to change the best-before dates, I stopped buying any meat products from the Real Canadian Superstore."

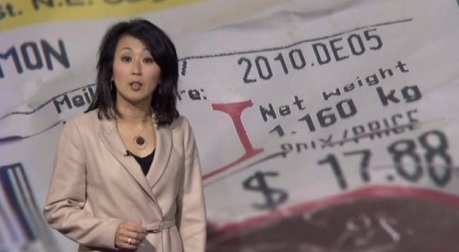

and if they smelled okay, we re-wrapped them and put a new best-before date, extending usually by about five days. When we were told to change the best-before dates, I stopped buying any meat products from the Real Canadian Superstore." Dec. 5, but when it was re-wrapped, the new best-before date was Dec. 9.

Dec. 5, but when it was re-wrapped, the new best-before date was Dec. 9..jpg) best-before dates are maintained. We have reinforced this policy with the pertinent store…. We apologize if there is any concern on the part of our customers."

best-before dates are maintained. We have reinforced this policy with the pertinent store…. We apologize if there is any concern on the part of our customers." them about high bacteria levels in shellfish.

them about high bacteria levels in shellfish. The P.E.I. Shellfish Association suggests putting yellow warning flags in the water when there’s a possible closure and a red one when the fishery is shut down.

The P.E.I. Shellfish Association suggests putting yellow warning flags in the water when there’s a possible closure and a red one when the fishery is shut down..jpg) brand name is often meaningless.

brand name is often meaningless. really interested in eggs that were verified through some kind of testing to be salmonella-free. Or reduced levels. Anything but the marketing crap that currently dominates the nation’s grocery shelves.

really interested in eggs that were verified through some kind of testing to be salmonella-free. Or reduced levels. Anything but the marketing crap that currently dominates the nation’s grocery shelves. And shopping for food can be so confusing.

And shopping for food can be so confusing. The USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service plans to issue new proposed rules this fall.

The USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service plans to issue new proposed rules this fall.