People want to know about their food. Where it was grown, how, what’s been added and if it’s safe.

The N.Y. Times, as usual, gets that little bit right in a commentary yesterday, but wrongly thinks right-to-know is something new, that media amplification is something new because of shiny new toys, and offers no practical suggestions on what to do.

The term pink slime was was coined in 2002 in an internal e-mail by a scientist at the Agriculture Department who felt it was not really ground beef. The term was first publicly .jpg) reported in The Times in late 2009.

reported in The Times in late 2009.

In April 2011, celebtard chef Jamie Oliver helped create a more publicly available pink slime yuck factor and by the end of 2011, McDonald’s and others had stopped using pink slime.

On March 7, 2012, ABC News recycled these bits, along with some interviews with two of the original USDA opponents of the process (primarily because it was a form of fraud, and not really just beef).

Industry and others responded the next day, and although the story had been around for several years, the response drove the pink slime story to gather media momentum – a story with legs.

BPI said pink slime was meat so consumers didn’t need to be informed, and everything was a gross misunderstanding. BPI blamed media and vowed to educate the public. Others said “it’s pink so it’s meat” and that the language of pink slime was derogatory and needed to be changed. USDA said it was safe for schools but quickly decided that schools would be able to choose whatever beef they wanted, pushing decision-making in the absence of data or labels to the local PTA. An on-line petition was launched.

Sensing the media taint, additional retailers rushed to proclaim themselves free of the pink stuff.

BPI took out a full-page ad in the Wall Street Journal, the favored reading choice for pink slime aficionados, and four mid-west governors banded together to repeat the same erroneous  messages during a media-show-and-tell at a BPI plant. Because political endorsements rarely work, and the story had spread to the key demographic of burger eaters, others sensed opportunity in the trashing of BPI. Wendy’s, Whole Foods, Costco, A&P, Publix and others launched their own media campaigns proclaiming they’ve never used the stuff and never would.

messages during a media-show-and-tell at a BPI plant. Because political endorsements rarely work, and the story had spread to the key demographic of burger eaters, others sensed opportunity in the trashing of BPI. Wendy’s, Whole Foods, Costco, A&P, Publix and others launched their own media campaigns proclaiming they’ve never used the stuff and never would.

Guess they didn’t get their dude-it’s-beef T-shirts.

These well-intentioned messages only made things worse for the beef producers and processors they were intended to protect.

Here’s what can be learned for the next pink slime. And there will be lots more.

Lessons of pink slime

• don’t fudge facts (is it or is it not 100% beef?)

• facts are never enough

• changing the language is bad strategy (been tried with rBST, genetically engineered foods, doesn’t work)

• telling people they need to be educated is arrogant, invalidates and trivializes people’s thoughts

• don’t blame media for lousy communications

• any farm, processor, retailer or restaurant can be held accountable for food production – and increasingly so with smartphones, facebook and new toys

.jpg) • real or just an accusation, consumers will rightly react based on the information available

• real or just an accusation, consumers will rightly react based on the information available

• amplification of messages through media is nothing new, especially if those messages support a pre-existing world-view

• food is political but should be informed by data

• data should be public

• paucity of data about pink slime that is publicly available make statements like it’s safe, or it’s gross, difficult to quantify

• relying on government validation builds suspicion rather than trust; if BPI has the safety data, make it public

• what does right-to-know really mean? Do you want to say no?

• if so, have public policy on how information is made public and why

• choice is a fundamental value

• what’s the best way to enable choice, for those who don’t want to eat pink slime or for those who care more about whether a food will make their kids barf?

• proactive more than reactive; both are required, but any food provider should proudly proclaim – brag – about everything they do to enhance food safety.

• perceived food safety is routinely marketed at retail; instead market real food safety so consumers actually have a choice and hold producers and processors – conventional, organic or otherwise – to a standard of honesty.

• if restaurant inspection results can be displayed on a placard via a QR code read by smartphones when someone goes out for a meal, why not at the grocery store or school lunch?

• link to web sites detailing how the food was produced, processed and safely handled, or whatever becomes the next theatrical production – or be held hostage

.jpg) someone said, “I got sick and it was your strawberries,” the growers could at least say, “We don’t think it was us, and here’s everything we do to produce the safest product we can.”

someone said, “I got sick and it was your strawberries,” the growers could at least say, “We don’t think it was us, and here’s everything we do to produce the safest product we can.”.jpg) ingredient, some nasty sanitation, sorta suck.

ingredient, some nasty sanitation, sorta suck..jpg) searing on the outside will take care of any poop bugs like E. coli and the inside is clean. But what if needles pushed the E. coli on the outside of the steak to the inside?

searing on the outside will take care of any poop bugs like E. coli and the inside is clean. But what if needles pushed the E. coli on the outside of the steak to the inside?.jpg) were misleading.

were misleading. million 25-pound boxes for this winter season.

million 25-pound boxes for this winter season..jpg) PFGE pattern associated with this outbreak commonly occurs in the United States, some of the cases with this pattern may not be related to this outbreak. Based on the previous 5 years of reports to PulseNet, approximately 30-40 cases with the outbreak strain would be expected to be reported per month in the United States. The outbreak strain is different from another strain of Salmonella Heidelberg associated with ground turkey recalled earlier this year.

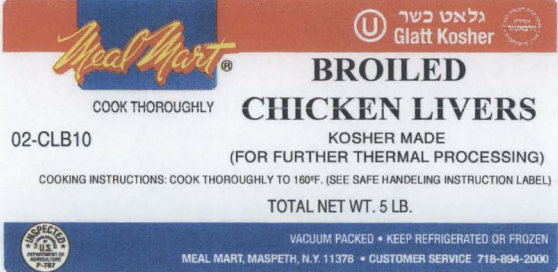

PFGE pattern associated with this outbreak commonly occurs in the United States, some of the cases with this pattern may not be related to this outbreak. Based on the previous 5 years of reports to PulseNet, approximately 30-40 cases with the outbreak strain would be expected to be reported per month in the United States. The outbreak strain is different from another strain of Salmonella Heidelberg associated with ground turkey recalled earlier this year. so on the label (right). Illnesses are also linked to chopped liver made from this product at retail stores. The outbreak strain of Salmonella Heidelberg was isolated by the New York State Department of Agriculture and Market from samples of broiled chicken livers from the establishment, and chopped chicken livers produced at retail from these livers. These products would have been repackaged and will not bear the original packaging information.

so on the label (right). Illnesses are also linked to chopped liver made from this product at retail stores. The outbreak strain of Salmonella Heidelberg was isolated by the New York State Department of Agriculture and Market from samples of broiled chicken livers from the establishment, and chopped chicken livers produced at retail from these livers. These products would have been repackaged and will not bear the original packaging information.

the Mother of all Fruits, which is affiliated with the Dutch-based retailer,

the Mother of all Fruits, which is affiliated with the Dutch-based retailer,

Garden, because “when you are here, your are family."

Garden, because “when you are here, your are family."