Note to journalists (if there are any left): Don’t reprint PR fluff like it’s news and don’t bury the lede.

“A good way to test your food is also a simple way: give it a sniff,” says Roni Neff, PhD. “If the date says ‘best by’ and it looks and smells okay, it’s probably okay to eat.”

Probably is not good enough, and smell is a lousy indicator of food safety.

Probably is not good enough, and smell is a lousy indicator of food safety.

A new survey examining U.S. consumer attitudes and behaviors related to food date labels found widespread confusion, leading to unnecessary discards, increased waste and food safety risks. The survey analysis was led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future (CLF), which is based at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

This study calls attention to the issue that much food may be discarded unnecessarily based on food safety concerns, though relatively few food items are likely to become unsafe before becoming unpalatable. Clear and consistent date label information is designed to help consumers understand when they should and should not worry.

Among survey participants, the research found that 84 percent discarded food near the package date” occasionally” and 37 percent reported that they “always” or “usually” discard food near the package date. Notably, participants between the ages of 18 to 34 were particularly likely to rely on label dates to discard food. More than half of participants incorrectly thought that date labeling was federally regulated or reported being unsure. In addition, the study found that those perceiving labels as reflecting safety and those who thought labels were federally regulated were more willing to discard food.

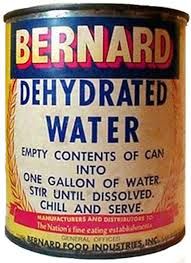

New voluntary industry standards for date labeling were recently adopted. Under this system, “Best if used by” labels denote dates after which quality may decline but the products may still be consumed, while “Use by” labels are restricted to the relatively few foods where safety is a concern and the food should be discarded after the date. Previously, all labels reflected quality and there was no safety label.

Neff and colleagues found that among labels assessed, “Best if used by” was most frequently perceived as communicating quality, while “use by” was one of the top two perceived as communicating safety. But many had different interpretations.

Lead author, Roni Neff, PhD, who directs the Food System Sustainability Program with the CLF and is an assistant professor with the Bloomberg School’s Department of Environmental Health and Engineering said, “The voluntary standard is an important step forward. Given the diverse interpretations, our study underlines the need for a concerted effort to communicate the meanings of the new labels. We are doing further work to understand how best to message about the terms.”

Lead author, Roni Neff, PhD, who directs the Food System Sustainability Program with the CLF and is an assistant professor with the Bloomberg School’s Department of Environmental Health and Engineering said, “The voluntary standard is an important step forward. Given the diverse interpretations, our study underlines the need for a concerted effort to communicate the meanings of the new labels. We are doing further work to understand how best to message about the terms.”

How best to message about the terms? Maybe use language properly.

Using an online survey tool, Neff and colleagues from Harvard University and the National Consumers League assessed the frequency of discards based on date labels by food type, interpretation of label language and knowledge of whether date labels are regulated by the federal government. The survey was conducted with a national sample of 1,029 adults ages 18 to 65 and older in April of 2016. Recognizing that labels are perceived differently on different foods, the questions covered nine food types including bagged spinach, deli meats and canned foods.

When consumers perceived a date label as an indication of food safety, they were more likely to discard the food by the provided date. In addition, participants were more likely to discard perishable foods based on labels than nonperishables.

But dates can be a lousy indicator: I’ve got deli meat in the fridge with a use by label about 2 weeks from now, yet once that package is opened, the stuff is good for 2-4 days. Publix gets it right.

Smell, like color, is a lousy indicator of food safety.